Sonia Delaunay was many things: the Ukrainian Jewish daughter of a nail factory foreman who eventually made her way in the art world; the proprietor of a French fashion house; the only woman to have an exhibition at the Louvre in her lifetime. Any of these feats on their own warrant a retrospective, but the Bard Graduate Center in New York is mounting an impressively comprehensive exhibition that tells the entire story of Delaunay’s remarkable life and career. Coming at the end of February, Sonia Delaunay: Living Arts will bring together more than two hundred works from a pantheon of international collections, demonstrating Delaunay’s incredible reach and commitment to her lively signature style.

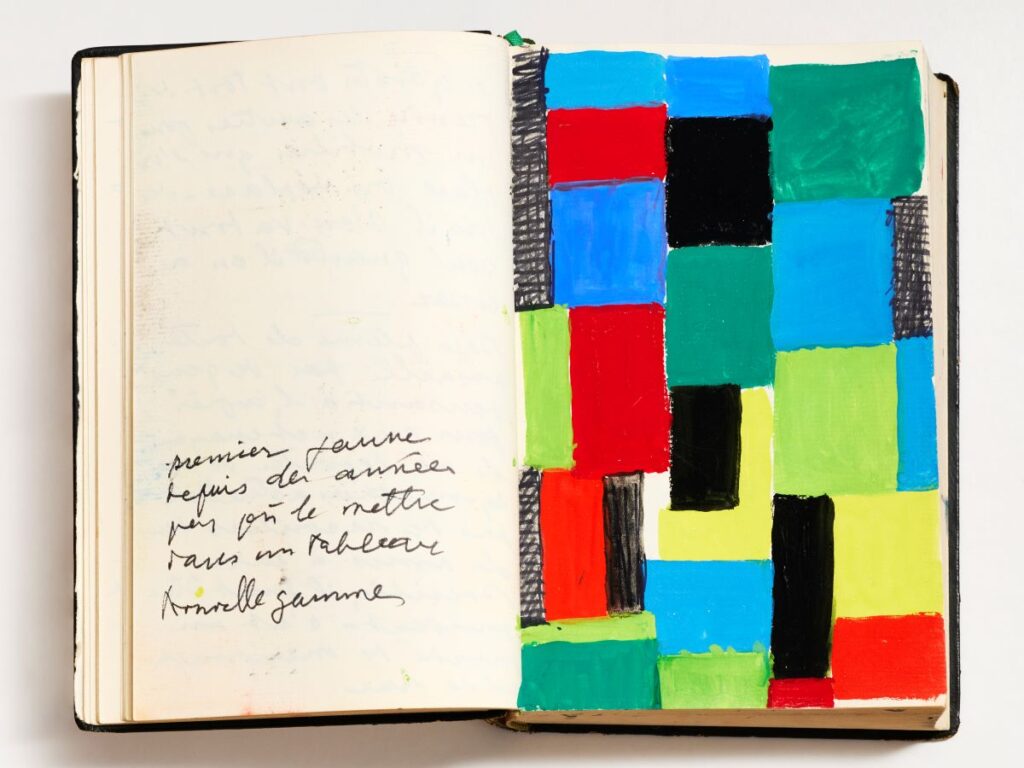

The Bard Graduate Center characterizes Delaunay’s output as “kaleidoscopic”—a perfect word to describe both her sustained influence on twentieth-century modernism and the visual quality of her art. Early on, she was inspired by nascent cubism and explored the abstraction of form through painting. Her work eventually departed from that of her cubist forebears, and her style matured into an interpretation of spiritual abstraction, similar to that practiced in Eastern Europe by the likes of Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky.

Together with her husband, painter Robert Delaunay, she contributed to an emergent movement known as Orphism. Orphism—so named after mythological poet Orpheus—combined the geometric abstraction of cubism with the poetic use of color favored by the fauvists. Delaunay continued to apply her signature Orphist style to an endless range of materials: furniture, fabrics, wall coverings, and beyond.

Delaunay’s first major foray into a long career in textile design occurred in 1918 when she was commissioned to produce designs for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Art deco-era Egyptomania meets geometric modernism in Delaunay’s structural gown created for the title character of Diaghilev’s Cleopatra. A stylized portrait of dancer Lubov Tchernicheva wearing the costume, painted by English artist Flora Lion, is especially evocative. Later examples of Delaunay’s consumer fashions provide an intriguing counterpoint. From stage to street, Delaunay excelled in adornments for the avant-garde woman, applying her blocky textile designs to hats, scarves, dresses, and accessories. A felted cloche hat and matching scarf on exhibit feel especially of-the-moment, while Robert Delaunay’s portrait of Madame Mandel in distinctly Sonia-esque garb gives context to the broader community of edgy, upper-class creatives who delighted in these designs.

Rare examples of furniture created by Sonia Delaunay for her family home offer another interpretation of “living art” and make up the center of the Venn diagram for this exhibition of both personal objects and those made for the public. A 1923 sideboard from the Delaunays’ Paris apartment is on loan from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, to which it was left by Delaunay herself. The Delaunays lived and breathed the pillars of Orphism: that shape and color could transmit feelings and create a sense of place.

Following her beloved husband’s death in 1941, Delaunay kept busy. She published the illustrated volume Rythmes-Couleurs in 1966, which features eleven geometric stencils accompanied by written works from her friend, poet Jacques Damase. In the late 1960s, she was commissioned by the CEO of Matra Automobiles to design the body paint for a 530 coupe, which she adorned with patchwork squares of color. By the 1970s, Delaunay was a living legend. She published her autobiography, Nous Irons jusqu’au Soleil (We Shall Go Right up to the Sun), in 1978 and died one year later at ninety-four.

The impressively broad exhibition Sonia Delaunay: Living Art is both ambitious and necessary: it would be impossible to tell Delaunay’s story without relaying the interconnectedness of her work. The sheer volume of art she produced over her sixty-year career leaves curators with the unenviable task of narrowing the scope to a bite-size selection of works for gallery display. An accompanying catalogue fills in the gaps. For anyone who craves twentieth-century modernism beyond Picasso and his cubist clique, this exhibition is not to be missed.

Sonia Delaunay: Living Art • Bard Graduate Center, New York • February 23–July 7, 2024 • bgc.bard.edu