Readers of this magazine will remember design historian Sarah Coffin’s 2022 feature article on art nouveau architect-designer Hector Guimard and his wife, artist Adeline—a sneak peek at the traveling exhibition Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism, the first stateside retrospective on Guimard’s prodigious output in more than six decades. The show has arrived at Chicago’s Driehaus Museum, with some one hundred pieces of furniture, jewelry, metalwork, ceramics, drawings, and textiles dating from the Belle Époque and interwar period taking their place among the Gilded Age appointments of the 1883 Samuel S. Nickerson House, home of the Driehaus.

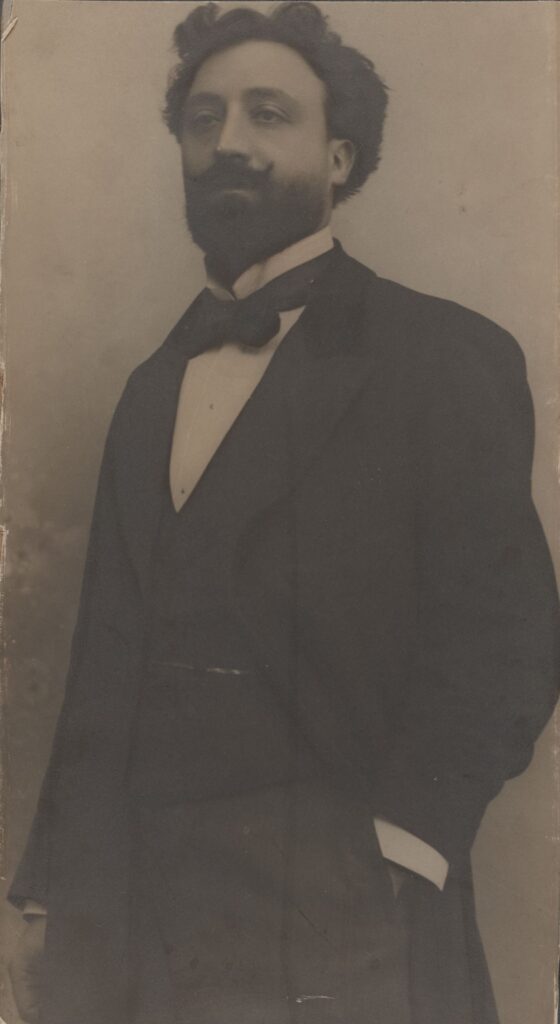

Guimard was born in Lyon, France, the son of an orthopedist and a maid. Accepted to the prestigious École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts as a teenager, he displayed little interest in schooling, and in 1888 opened an architectural firm despite having no professional experience in the field. A socialist, Guimard advocated for design reforms that would simplify the building process, an interest that attracted him to the work of Gothic revivalist Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, as well as to the British designer Christopher Dresser, who combined mass-market materials, such as cast iron and wall coverings, with a biomorphic aesthetic developed from his studies in botany. Guimard adopted the naturalistic idiom for his art nouveau masterpiece the Castel Beranger, built between 1895 and 1897, for which he designed everything in the house, from wallpapers to elements in Lincrusta, the embossed paper-and-linseed-oil wall covering developed in part by Dresser.

Guimard’s big break—and the project for which he is best known today—came in 1900, when on the occasion of that year’s Exposition Universelle he was commissioned to design new entryways for the Paris subway. A keen and inventive self-promoter, Guimard parlayed his newfound fame into partnerships with the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, the Saint-Dizier Foundries (for works in cast iron), and Langlois (for glass-pendant lamps and light fixtures). Within a few years, he also wooed and wed Adeline Oppenheim, a painter from a wealthy American family, for whom he built his magnum opus, the Hôtel Guimard, a four-story town house and showroom in the 16th arrondissement.

Art nouveau was on the wane by 1910, plowed under by the nascent art deco style. Following World War I, Guimard turned his attention to affordable housing designs, and founded the company Standard-Construction in 1921 to investigate options for prefabricated buildings made of wood, reinforced concrete, and steel. Although he applied for eleven patents—for a paneled roofing system, blocks of interlocking composite stone, and wooden construction scaf- folds, among other inventions—Guimard found little success, his efforts outshone by other mass-production innovations of the period such as Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-Ino rowhouse system. The Guimards left the country during the buildup to World War II, settling in New York, where Guimard would die, almost forgotten, four years later.

Adeline spent the next quarter century securing his legacy with the help of Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr Jr., placing objects related to her husband’s career in stateside academic libraries and museums such as the Cooper Hewitt and MoMA. The present exhibition thus represents a reunion, of sorts, for long-ago dispersed objects such as a model for Madame Guimard’s gold engagement ring and a sinuous pear wood, leather, and brass side chair, which would have given evidence of Hector Guimard’s all-encompassing design sense to anyone who visited his home.

Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism • Richard H. Driehaus Museum, Chicago • to November 5 • driehausmuseum.org