Chicago has had its share of idiosyncratic artists, Gertrude Abercrombie and Ivan Albright among them. Neither an avant-garde bohemian like Abercrombie, nor determinedly transgressive like Albright, ceramist Ruth Duckworth nonetheless stood as a singular figure in the city’s art scene. She pursued a medium that was long deemed more craft than art, but, like other sculptors of her day such as Peter Voulkos, worked determinedly to elevate ceramics to the level of fine art. As she told The Art Newspaper in 2006, “Potters throw on a wheel and build up; I begin with clay and take away. . . . I remove rather than build.” This month, the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago—where Duckworth was a long-time faculty member—presents Ruth Duckworth: Life as a Unity. The first major show of her work since a 2005 retrospective organized by the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, the exhibition looks closely at the range of her endeavors, from small artworks to large-scale installations.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, and artistic from an early age, Duckworth left for England to study art in 1936 at age seventeen. Her father was a Jew, and Nazi laws forbade her to have an arts education. She first studied across all mediums at the Liverpool College of Art, and later rode out the war working, in part, in a munitions factory. She resumed her studies in London and, after seeing a show of pottery from India, enrolled in 1956 at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Within a short time, “Duckworth began to create vessels and sculptures that were radically freeform, organic, and liberated from the tyranny of function,” as a 2006 exhibition preview noted. “Most importantly, she demonstrated that clay was a viable medium for sculpture.” Though pottery purists scoffed at her work, favoring the traditional vessels created by Lucie Rie, Hans Coper, and others, Duckworth’s sculptures created a sensation among cutting-edge ceramists in Britain and around the world.

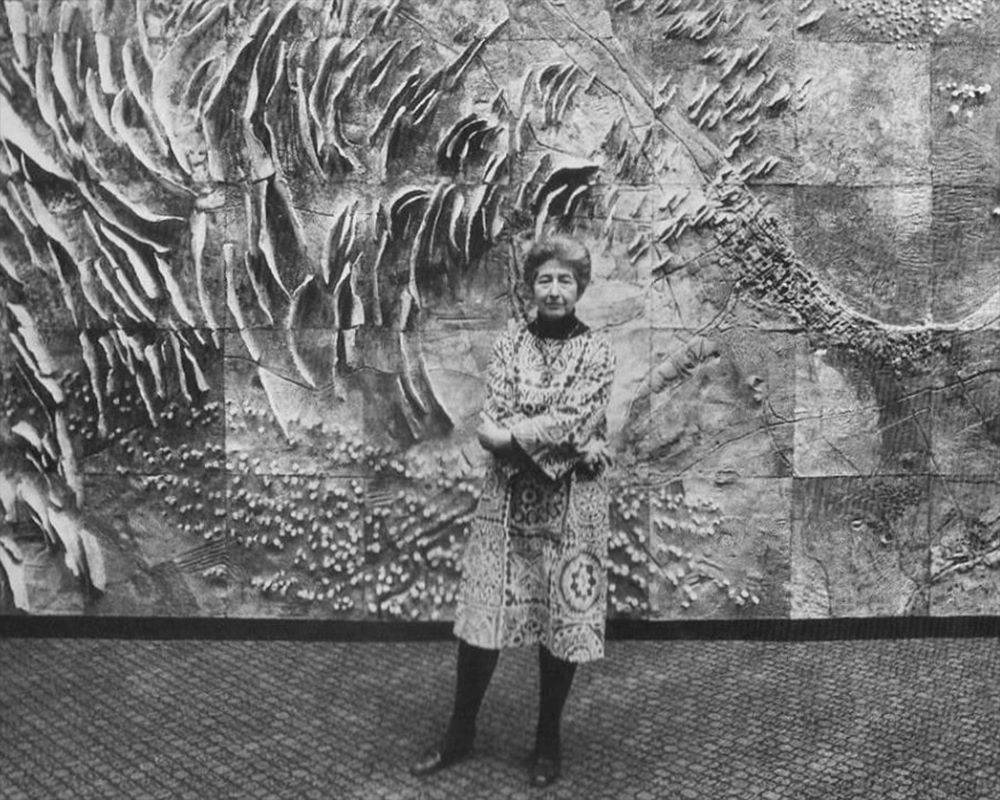

Influences on Duckworth’s sculptures range from the biomorphic modernism of Henry Moore and Constantin Brancusi, to the simple, sober female figures seen in the Cycladic art of ancient Greece. But the earth itself—the shaping of land masses by water, weather, and tectonic movement—inspired many of Duckworth’s greatest works. Shortly after she accepted an invitation to teach at the University of Chicago in 1964, she received a commission to create a mural for the university’s then-new Geophysical Sciences building. Drawing from topographical maps and satellite images, Duckworth fashioned Earth, Water, and Sky, a four-hundred-square-foot constellation of glazed stoneware that covers the walls and ceiling of the lobby. (A second environmentally inspired Duckworth masterpiece, Clouds Over Lake Michigan, followed in 1976. Originally commissioned by a bank, the mural was recently donated to the university and installed in the main campus library.) The exhibition Life as a Unity, says Laura Steward, curator of public art at the Smart Museum, “is the result of the growth of ‘eco-criticism’ in the field of art history. This novel critical framework allows us to center the artist’s relationship with the natural world, which in Duckworth’s case was profoundly influenced by the satellite era and her engagement with the geophysical sciences at UChicago.”

Duckworth was generally reluctant to expound too specifically on the meaning or intent of her work, preferring, at times, to characterize it as instinctual, creative play. And while many of her pieces can be appreciated solely for their inventive formalism, it seems the artist—who saw her medium as an essential manifestation of life—did ponder the relationship between her efforts and the environment. In a statement for a 1993 exhibition at the Union League Club of Chicago, Duckworth wrote: “The Earth is so fragile and beautiful, it needs so much love and caring and not just by me. Can I express any of that in my work? I really don’t know.”

Ruth Duckworth: Life as a Unity • Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago • September 21 to February 4, 2024 • smartmuseum.uchicago.edu