The slow collapse of the Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coupled with European—particularly French—colonial expansion in the Middle East, contributed to an influx of Islamic art and design objects flowing into cities of the West. There, scholars, artists, designers, architects, and others saw in them a potentially rejuvenating aesthetic for then-modernizing Europe. The jewelry and watchmaking firm Cartier was no exception. The third-generation head of the Paris branch, Louis J. Cartier, and his workshop adapted Islamic motifs, materials, and methods of making into a strikingly original style that continues to be expressed in Cartier’s jewelry to this day. The exhibition Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity at the Dallas Museum of Art offers insight into the creative process of Cartier’s designers through more than four hundred objects from the firm’s own collection, and those of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (where the exhibition debuted last year), the Louvre, the privately owned Keir Collection of Islamic Art, and more.

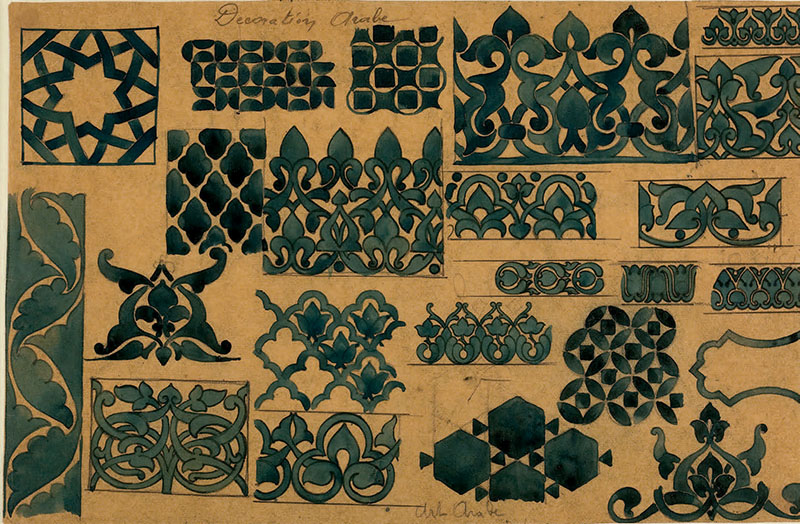

Louis Cartier’s personal collection of Islamic art and design, reassembled for the first time in nearly eighty years, was an indispensable resource for Cartier designers. Mostly portable objects produced for an urban elite, it includes artifacts such as illuminated Persian manuscript pages, walrus-ivory-and-silk pen boxes, jewel-encrusted daggers, and, perhaps most importantly, sourcebooks of Ottoman, Arabic, or polychrome design work. Cartier and his designers isolated Islamic motifs like S-curves, arches, and pyramidal merlons—a decorative architectural element found along the rooflines of mosques—and adapted and integrated them into the firm’s design vocabulary.

In the exhibition at the DMA, the flow of ideas from East to West is presented in nine dimly lit galleries, where diamond and platinum necklaces, bracelets, pendants, and other more unusual forms glitter from shadowboxes and vitrines like so many stars. The exhibition was designed by New York–based architecture firm Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro, whose most noteworthy innovation is a series of four digital animations. Next to a display case that holds an eye-catching 1922 bandeau with coral cabochons set in platinum and gold, a wall-mapped projection of the same gradually morphs into the peristyle of an Iranian courtyard, and then back into a bandeau again.

Visual storytelling is one of the through lines of Cartier and Islamic Art’s curation and design. Instead of wall texts, each artifact is numbered, and there’s a booklet—prompting visitors to look first, read later. “I wanted people to become their own connoisseur,” says Sarah Schleuning, senior curator of decorative arts and design at the DMA. It’s an approach made possible in part by Cartier’s fastidious visual record-keeping. A drawing from Louis Cartier’s cahier d’idées—or “idea notebook”—a plaster cast, and a black-and-white photograph chart the transformation of an idea inspired by a marquise-like Islamic motif into a necklace of platinum and diamonds. A nearby display juxtaposes three artifacts to suggest how the cartouche of a 1913 Cartier cigarette case ultimately derives from an embossed leather bookbinding plate from Turkey.

Jewelry that came out of the firm’s workshops in the 1910s and 1920s frequently made use of apprêts, or fragments of existing jewels, objects, and textiles. Elements like pre-cut Indian stones were strung en masse to create the multicolored confections of Cartier’s Tutti Frutti style, popular in the latter decade. Such jewelry sported color-and-gem combinations never seen before in Europe. A pairing such as turquoise with lapis lazuli was evocative of Iranian tiles, and sapphires with emeralds rendered what Louis Cartier called “peacock decor.” Under the direction of Jeanne Toussaint, who took over as creative director of the Paris branch in 1933, the practice of incorporating antique elements expanded. Entire Indian jewelry pieces were disassembled and set in new arrangements. Toussaint’s attention also fell on North Africa. Colorful, opaque elements such as the vivid enamels typical of Algeria’s Kabylie region entered the Cartier tool kit, appearing in pieces such as a chunky 1971 necklace that incorporates gold, diamonds, amethysts, coral, chrysoprase, and lapis lazuli.

Although other exhibitions have explored the influence that countries such as India and China have had on the firm’s jewelry, Cartier and Islamic Art is the first to focus on the broader category of the Islamic world. Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s director of image, style, and heritage, explains that the firm “realized progressively that the non-Western forms incorporated into Cartier jewelry were linked to the Islamic world more broadly, rather than to specific Eastern countries.” As such, the exhibition fills a significant plot hole in both Cartier’s own story of itself, and in the history of Islamic design influence on the West. The hope is that viewers walk away thinking about “what it means to be inspired” by objects from the past, Schleuning says, as “across time, mediums, and geography, artists create new ideas.”

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity • Dallas Museum of Art, Texas • to September 18 • dma.org