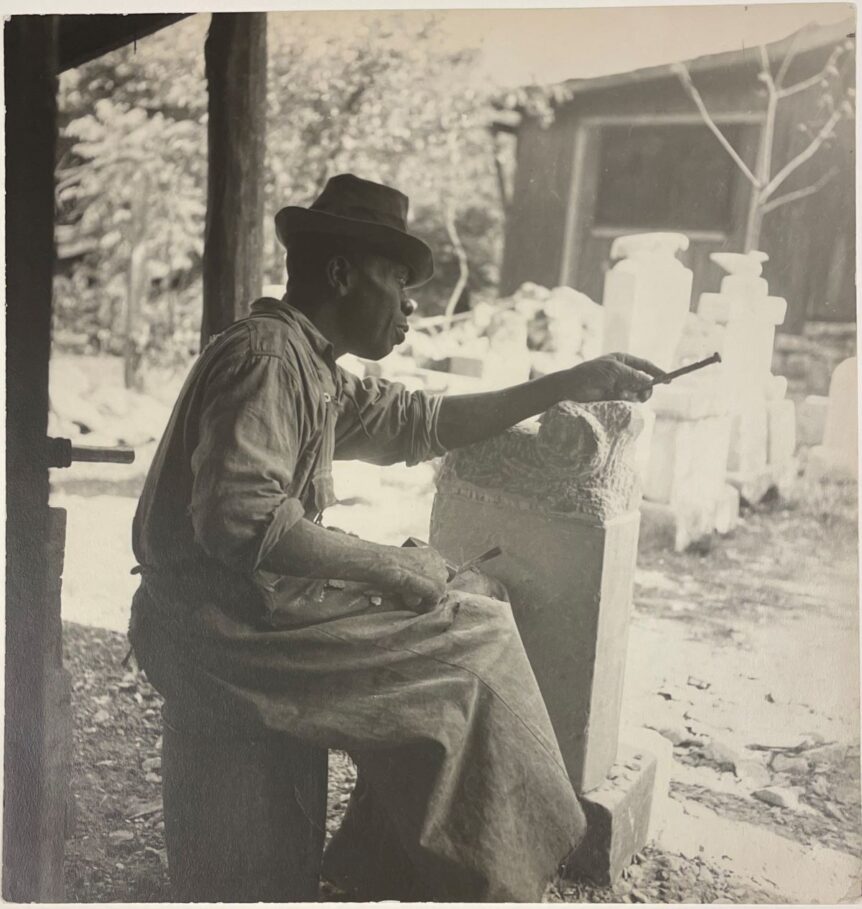

The sculptor William Edmondson is simultaneously one of the most famous and one of the least known members of the pantheon of great American self-taught artists. Born in rural Tennessee in 1874, on the same plantation where his parents were once enslaved, he had lived a modest and unremarkable life—working variously as a racehorse groom, on the railroad, and as a Nashville hospital orderly—until 1931. Edmondson offered little explanation why then, at the age of fifty-seven, he raised a sign advertising “Tombstones and Garden Ornaments” at his Nashville home and began to sculpt angels, animals, and Biblical characters from blocks of limestone, other than to say he was answering a call from the divine. “Jesus has planted the seed of carving in me. I was out in the driveway with some old pieces of stone when I heard a voice telling me to pick up my tools and start to work on a tombstone. . . . He hung a tombstone out for me to make . . . then he told me to cut figures,” Edmondson told a reporter in 1937.

That was the year Edmondson and his art came to wide public notice, in comparatively spectacular fashion: as the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Word of Edmondson’s creations had spread among academics and others in Nashville cultural circles, and eventually reached the ears of Alfred Barr, MoMA’s director. The Edmondson show has become famous as a watershed curatorial moment—the museum’s first solo show for a Black artist, as well as its first exhibition of a self-taught artist. But what’s less remembered is the critical response to it, which can be described as appreciative condescension. Edmondson was a “find” and a “discovery”; his work was “naïve” and “primitive” and marked by a charming “simplicity.” (In its reportage, Time magazine’s attempt to re-create Edmondson’s southern diction is particularly cringe-worthy.)

Views have evolved over the decades. A new exhibition at the Barnes Foundation, which presents some sixty examples of Edmondson’s work, reassesses his art on its own terms. Edmondson emerges as an artist of complex motivations, whose creative expression derived not only from deeply held religious beliefs, but also from immemorial communal traditions and the facts of life as a Black man in the era of Jim Crow. Confronted with “racial biases, and poverty, and denied the opportunity to obtain an education at the most foundational level, William Edmondson transcended these harsh systemic realities,” art historian Leslie King Hammond notes in the exhibition catalogue. “He was an artist empowered by unwavering faith, epiphanies, and acute artistic sensibilities to stealthily navigate strategies of divine revelation, indomitable resilience, and resistance.”

William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision • Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia • to September 10 • barnesfoundation.org