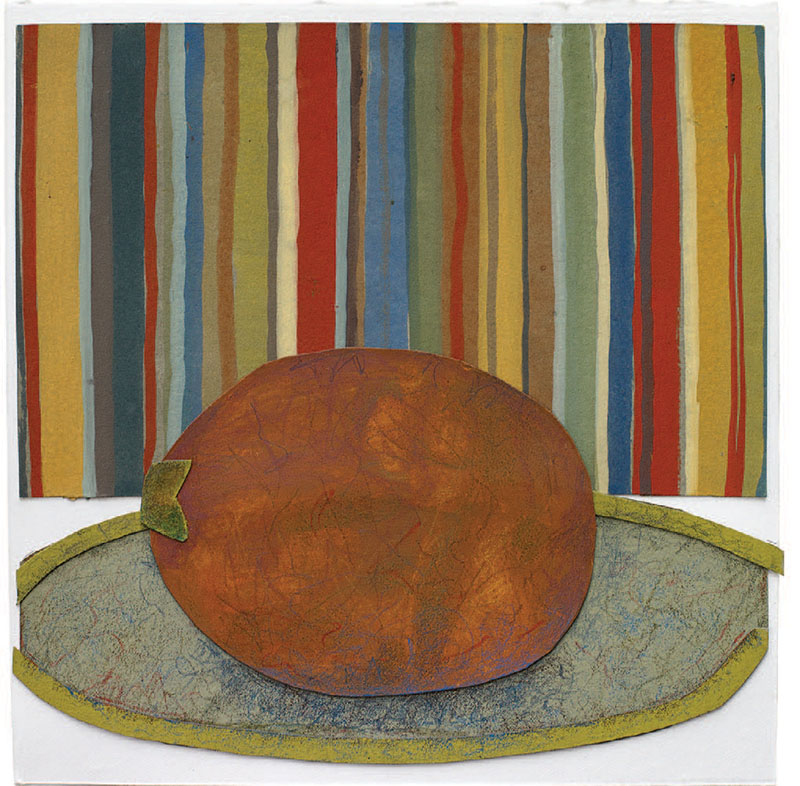

Journalism isn’t supposed to be fun. But it was a genuine pleasure working on our “Living with Antiques” cover story thanks to its subjects, Marc Brown and Laurene Krasny Brown, two remarkable people. They are warm, wise, generous, whip smart, intellectually curious, engaging, boundlessly patient—thank heaven—and they radiate creativity. Laurie is an artist whose primary medium is paper, while Marc is the creator of the Arthur children’s book and television series. (He also conceived the tableau of Shaker boxes for our cover.)

You can see some of the Browns’ work on this page, and learn much more about them and their folk and self-taught art collection in Stacy C. Hollander’s excellent article, which is illustrated with superlative photos taken by Ellen McDermott with the help of Bridget Sciales.

Patrick Bell, the proprietor, with Edwin Hild, of the esteemed folk art gallery Olde Hope Antiques, was instrumental to making this cover story possible, and my cup runneth over with gratitude. Thanks, Pat!

Word came in late May that a venerable member of our media tribe had passed away: Roger Angell, a longtime fiction editor for the New Yorker, who died at age 101. Though he blue-penciled the likes of Nabokov and Updike, most readers knew Angell chiefly for his sideline as the magazine’s baseball writer. At that job, he was the best—as most every other baseball writer will cheerfully tell you. Angell covered the game with extraordinary eloquence, insight, reportorial acumen, and—perhaps most importantly— with a fan’s passion.

I am put in mind of a marvelous passage in one of Angell’s finest articles, “Agincourt and After,” an account of the epic 1975 World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Red Sox. It is a rumination on fandom:

What I do know is that this belonging and caring is what our games are all about; this is what we come for. It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitative as a professional sports team, and the amused superiority and icy scorn that the non-fan directs at the sports nut (I know this look—I know it by heart) is understandable and almost unanswerable. Almost. What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring—caring deeply and passionately, really caring—which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives. And so it seems possible that we have come to a time when it no longer matters so much what the caring is about, how frail or foolish is the object of that concern, as long as the feeling itself can be saved. Naïveté—the infantile and ignoble joy that sends a grown man or woman to dancing and shouting with joy in the middle of the night over the haphazardous flight of a distant ball—seems a small price to pay for such a gift.

If you squint, you can see how Angell’s words apply to those of us who love the art and design of the past, and the history, the skill, and the genius they embody. A chair is just some pieces of wood, except it’s not. To care about that chair—or that painting, or that earthenware pot, or that whatever—gives us a sense of belonging, of a place in the grand scheme, and a feeling that we’re connected both to past lives and to each other. It is, as Angell said, a gift to have such a sensibility. And, let’s face it: a capacity for caring seems to be in just as short supply these days as when Angell wrote those words nearly fifty years ago.

— Gregory Cerio