After a blisteringly hot and humid summer, I am so happy that we’ve entered September and are on our way to my favorite season of the year. Fall is wonderful everywhere, but it’s particularly special here in New York. When the air gets a crisp snap, it’s a pleasure to spend time outdoors again, and New York is a city for walking. One of my favorite late afternoon pastimes is to stroll along the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, with its views across the harbor, lower Manhattan, and the Brooklyn Bridge.

The fall sky above the city has a luminous clarity I don’t have the power to describe. Against that cerulean backdrop, when the leaves begin to turn, Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park become two of the most beautiful urban garden spots in the world. To enjoy the region’s autumn atmosphere to even more spectacular effect, take a short train ride up the Hudson River, to the precincts where Thomas Cole and Frederic Church painted their masterful landscapes, and marvel at the magnificent sweep of orange, red, yellow, and brown across the flanks of the Catskill Mountains.

Another reason I love the fall is that it’s the time of year for the eerie and supernatural—thanks most of all to Halloween, of course; but doesn’t it seem that all Gothic horror stories, or at least as translated into movies and television shows, are set on a chill autumn night under a full moon?

In the spirit of the season, I want to draw your attention to an exhibition currently on view at the Bennington Museum called Haunted Vermont. Among the New England states, Massachusetts leads the league in the macabre—it’s hard to top the Salem witch trials and Lizzie Borden—but Vermont has seen its full share of weirdness. As curator Jamie Franklin writes in his exhibition notes, the show draws on a “rich framework of historical tales of monsters, ghosts, missing persons and the occult from our own backyard.”

Among others, Haunted Vermont tells the stories of the Demonic Vampire of Manchester, a local sensation in the 1790s; of the state’s only witch trial, which took place in the late eighteenth century and resulted in the acquittal of one Widow Krieger after she sank rather than floated—a sure sign of sorcery—when thrown into the Hoosic River; and of the Bennington Triangle, a mountainous area northeast of the city in which several people mysteriously vanished without a trace in the 1940s and ‘50s.

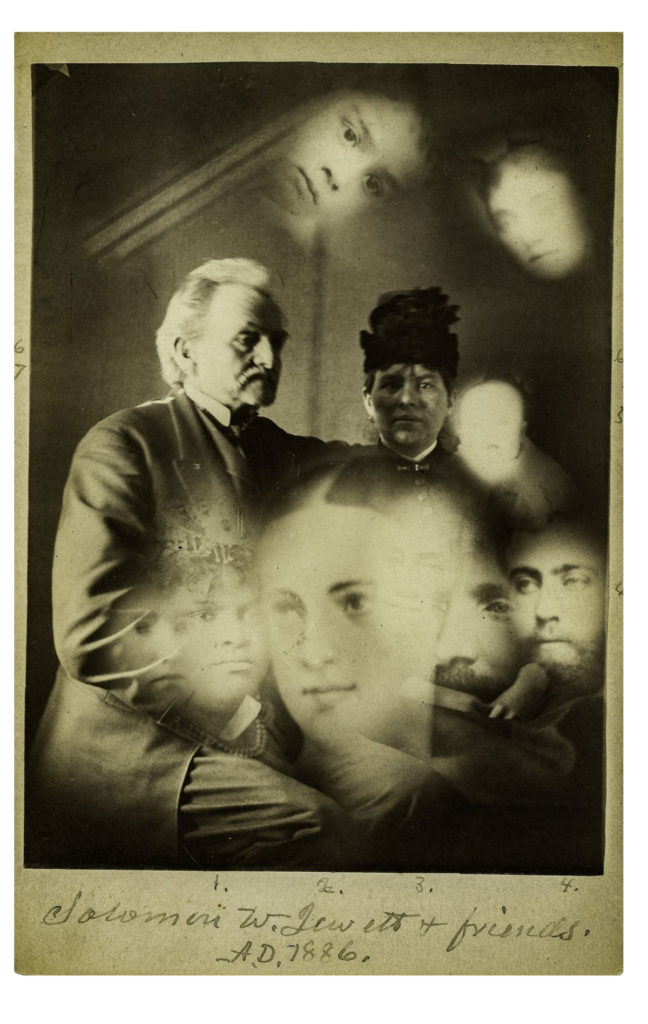

The show also details Vermont’s experience with spiritualism, a nineteenth-century quasi-religion that centered on the belief that the living could communicate with, and learn from, the dead. Solomon Jewett, a wealthy sheep farmer from the state who became obsessed with spiritualism, is a particular focus of the exhibition. He traveled the country attending seances and the like, and assembled a large collection of “spirit portraits.” Drawn by artists attending the seances, these depicted the ghosts of the dead, or the “spirit guides” to the hereafter—often Native Americans, such as the seventeenth-century Wampanoag leader Metacom, known as King Philip to British colonists—who supposedly directed mediums to whichever departed spirit they sought.

Among the most interesting artifacts in the exhibition are the “spirit photographs” Jewett commissioned that purported to document the ghostly specters who visited him as his picture was taken. The images seem like laughable nonsense today, but they were convincing proof of the afterlife for many people in an era when photography was still seen as an astonishing technology that was just beginning to reveal its capabilities.

Last, if like me you have never quite outgrown a taste for the kind of unsettling tales spun by writers from Edgar Alan Poe to Daphne du Maurier, Haunted Vermont features a large section devoted to longtime Vermont resident Shirley Jackson, author of such classic stories as “The Lottery” and “The Haunting of Hill House.” The museum recently received a gift of her papers and personal effects, and, if the items on view aren’t exactly compelling—the oddest is a “haunted music box” that Jackson said would start up by itself from time to time—they will be of passing interest to fans of her work, and certainly valuable to literary scholars.

So there’s a nice autumn itinerary for you: ghosts and goblins in Vermont; leaf-peeping there and in the Hudson River valley; and just about anything you want in New York City.