By 1888 the actor Edwin Booth had been through life’s wringer, and then some. In 1863 his wife, Mary Devlin, the great love of his life, died suddenly of pneumonia. Two years later, his fanatical brother John’s assassination of Abraham Lincoln brought down disgrace and vilification on the family and prompted Booth to retire from public life for a year. Then, in 1874, he lost his pride and joy—his own five-year-old, state-of-the-art theater at Twenty-third Street and Sixth Avenue in New York City—when bankruptcy forced him to close the business.

But now, fourteen years later, Booth had restored his fortune, his family honor, and his reputation as America’s greatest Shakespearean actor by dint of long, hard work and exemplary living. Booth had been performing onstage since at least age sixteen, and at fifty-six he looked forward to settling down a bit. One of the elements of a comfortable middle age that Booth had long contemplated was the founding of a social club for actors, one modeled on the Garrick Club in London, which had been established as a place “actors and men of refinement could meet on equal terms.”1 Booth pictured his club as a place where he could live himself and keep his library and vast collection of theatrical artifacts. Above all, though, it would be a refuge for gentlemanly conviviality. “I want real men who will be able to realize what real men actors are,” as Booth described prospective members to actress Kitty Goodale while they crossed the Rockies in his private railroad car in 1887. “I want my club to be a place where actors are away from the glamour of the theater.”2

That brawny vision became a reality on December 31, 1888, with the founding of The Players—a club name suggested by the “All the world’s a stage” speech from Shakespeare’s As You Like It. That evening, in a staid ceremony, Booth signed over the deed of his recently purchased town house on Gramercy Park to the new organization—which the architect Stanford White was in the midst of remodeling, with a colonnaded two-story porch festooned with elaborate wrought-iron lanterns—together with his books, art, and theatrical memorabilia collections. The Deed of Gift, as the club’s founding document is known, outlines Booth’s vision for the use of 16 Gramercy Park South: as a social club where actors might convene with men of other professions; as a repository for his theatrical library and collection for posterity and scholarship; and, finally, as his own home, with a third-floor apartment set aside for his personal use. The diverse interests and achievements of the sixteen charter members of the club on hand for the ceremony reflect the mix of talents Booth envisioned coming together. The group included noted actors of the day such as Lawrence Barrett, John Drew, and Joseph Jefferson, as well as Mark Twain and William Tecumseh Sherman.

Unlike almost all of New York’s storied social clubs—among them the Century Association, the Grolier, and the Salmagundi—The Players still occupies its original location. The club has thrived in the 145 years since its founding; and if it took a glacially long time to include other than “real men” among its ranks—women were not admitted as members until 1989, with an inaugural class that included Helen Hayes and Toni Morrison—The Players has earned a reputation as the least-starchy of the city’s great clubs, and the most hospitable and spirited.

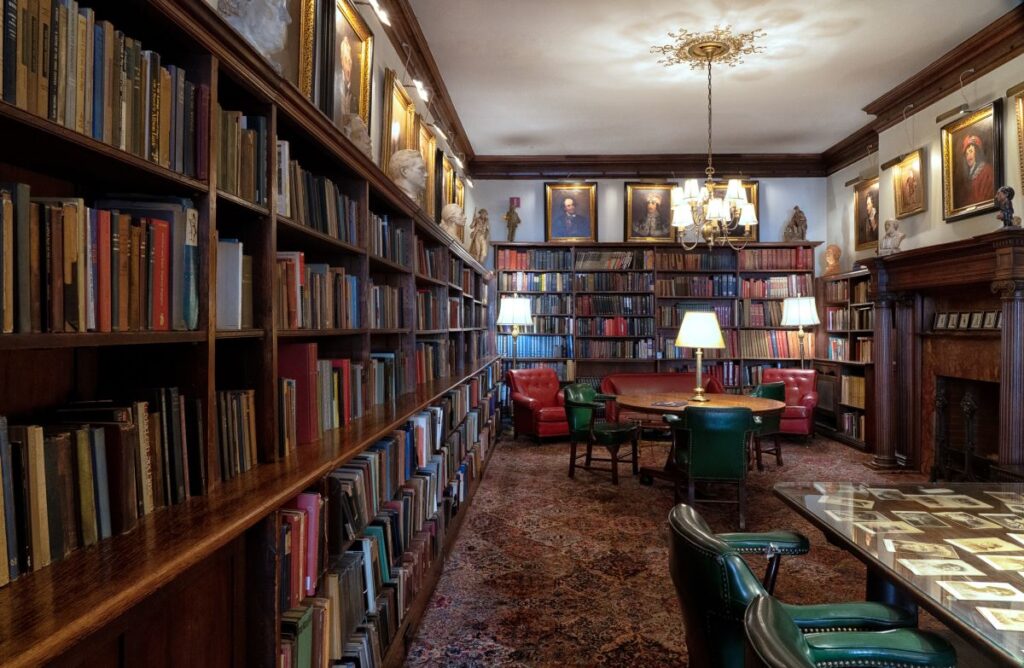

Still, all is not witty banter and hijinks here. The club’s non-profit adjunct, The Players Foundation for Theatre Education, is charged with maintaining the library and art collection and making them accessible to scholars and students. Built on the books and papers in Booth’s original bequest and augmented over the years with the holdings of other actors, the library—housed in a charming second-floor space with nineteenth-century appointments—includes books and manuscript letters, theatrical artifacts, costumes, photographs, and ephemera as well as some fifty thousand playbills (Fig. 6). The foundation is engaged in ongoing restoration of the art collection, which was built on member gifts, commissions, and special acquisitions, and includes works by such artists as Thomas Gainsborough, John Singer Sargent, James Montgomery Flagg, and Norman Rockwell. The club once owned a full-length 1890 portrait of Booth by Sargent, but it was deaccessioned in 2002 and is now in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum in Texas (Fig. 4).

The foundation is also responsible for the care and preservation of perhaps the most fascinating space at The Players: the apartment where Booth lived until his death in 1893. For the last several years, the bedroom-and-parlor suite had been kept in darkness to prevent sunlight from damaging fabrics and artworks, but the rooms have now undergone the first phase of a sparkling restoration. With all things kept as they were in Booth’s lifetime, the apartment is a veritable time capsule preserving the accoutrements with which a Gilded Age man-about-town surrounded himself. Aside from tidy furnishings—a brass bed, inlaid mahogany dressing table, rolltop desk for business papers—the rooms contain a number of personal and professional artifacts, including a skull used in productions of Hamlet, a portrait of Mary Devlin, a bronze casting of Booth’s daughter Edwina’s hand in his, and a shrine to Shakespeare that features a bust of the bard and a rubbing of the inscription on his grave (Fig. 10). A tobacco fiend like most men of his time and station, Booth also left behind an assortment of cigarette and cigar cases, tobacco pouches, a humidor, and other smoking paraphernalia (Fig. 14). Until recently, it was said, the scent of tobacco still hung in the air of Booth’s rooms.

Speaking of smoking, one of the longstanding traditions of The Players is its annual Pipe Night. Originally late-night gatherings at which members smoked long-stemmed churchwarden pipes and got up to who knows what mischief, the evenings evolved into testimonial dinners starting in 1936. John Gielgud was the first honoree, and over the decades such luminaries as Marlene Dietrich, Frank Sinatra, Lauren Bacall, and Morgan Freeman have been recognized. The latest honoree was Jane Curtin. Pipe smoking is no longer permitted on Pipe Night, of course—a fitting gesture for an institution with one foot in the past, and the other in the present. “I really believe that Edwin Booth and our founders would be delighted if they visited The Players today,” says film producer Townes Coates, current president of the club. “It’s true that our membership has grown in its richness and variety in ways they never imagined. But the commitment to build and protect our collections and preserve our clubhouse heritage makes it familiar across the generations. Plus, our greatest inheritance—the laughter and warmth and conviviality that always made this club unique—is something you find every time you walk in the door. It feels like home.”

1 Amelia Gentleman, “Time, gentlemen: when will the last all-male clubs admit women,” The Guardian, published online April 30, 2015.

2 Quoted in Katherine Goodale, Behind the Scenes with Edwin Booth (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1931), p. 256.

LANSING MOORE JR. is a New York–based historic preservationist and chair of the American Young Georgians, an association of under-forty art and design aficionados.