As we have sheltered in place the past few months, we are reminded of the ubiquity of glass in our environments. We gaze through window panes at the world beyond; we adjust lightbulbs made from blown glass to better illuminate us as we participate in online meetings or social events presented on the glass panels of our personal devices; we rely upon a network of fiberglass cables to keep us connected; and we reach for a tumbler or stemware to toast the end of another week. In less-exceptional times glass tended to recede into the background of our lives, but a forthcoming exhibition at the Corning Museum of Glass and its catalogue illuminate an earlier period when this material was ever-present and embodied the era’s cultural, social, and artistic achievements.

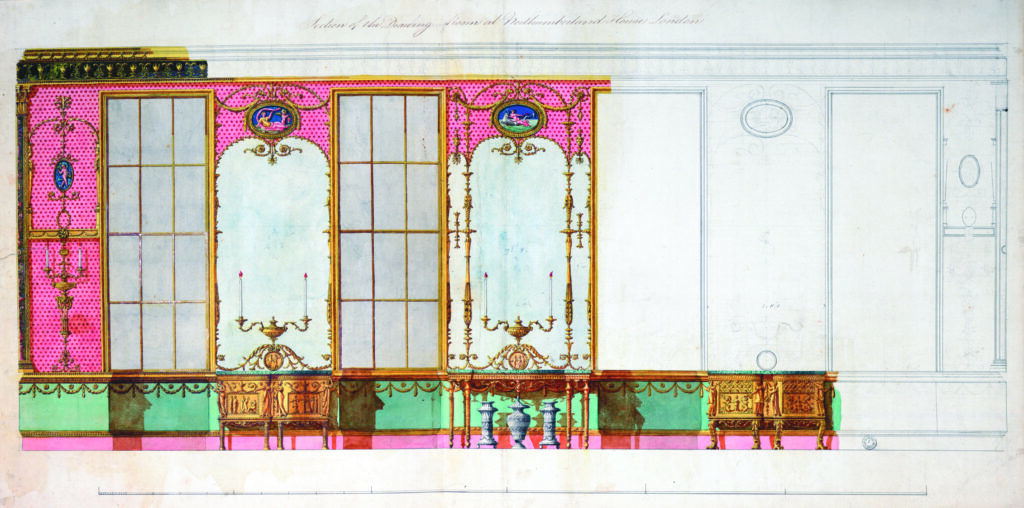

In Sparkling Company: Glass and the Costs of Social Life in Britain during the 1700s, organized by Christopher L. Maxwell, curator of early modern glass at the Corning Museum, was scheduled for this past spring and now will open in May 2021. The accompanying catalogue, In Sparkling Company: Reflections on Glass in the 18th-Century British World, is already available and brings together a refreshingly diverse array of objects that reveal the supporting role glass played in the British world in the eighteenth century. It was a self-fashioning period, where each decorating decision, each intellectual or leisurely pursuit, each item of clothing, and even each physical gesture announced one’s gentility and affirmed one’s position within a highly stratified society. Before being engaged by this intellectually refined world, glass undertook its own journey of physical refinement beginning in the mid-seventeenth century. The desire for transparent, colorless glass fueled the importation of Italian wares into England as well as the local production of Venetian-style glass, eventually leading to the introduction of dazzlingly clear lead glass by manufacturers in the Netherlands and England, the most famous being George Ravenscroft.1 Concurrently, glasshouses in England and on the Continent expanded their ability to produce ever-larger panes to be fitted into windows or silvered for mirrors and incorporated into architectural settings designed by the likes of John Linnell or Robert Adam (Fig. 2). The popularity of glass among eighteenth-century consumers was not due solely to its increased availability, but also to how it embodied the ideals of the time. The Irish philosopher Edmund Burke attempted to define the nature of beauty in his 1757 essay A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, noting that a “property constantly observable in such objects is Smoothness: A quality so essential to beauty, that I do not now recollect any thing beautiful that is not smooth.”2 Thus the unwavering expanses of windowpanes and mirrors, garniture sets blown into rounded forms, and even the facets of prismatic cutting proclaim their beauty through their smooth surfaces that invite touch and reflect and refract light. As Jennifer Y. Chuong notes in the exhibition catalogue, by the end of the century the allure of glass-like smoothness extended to furniture through the popularization of veneers and highly polished finishes. In all its variations, glass helped define the eighteenth-century interior in terms of social ideals as well as fashion.

Glass also adorned the bodies moving through these architectural spaces. Glass-paste stones were set into buttons, stomachers, hair ornaments, and buckles for shoes, belts, and neckpieces; they decorated fans and swords; and they were sewn into clothes with such profusion that it is clear they were appreciated on their own merits and not just as stand-ins for diamonds or emeralds. Indeed, glass could be made in vibrant, saturated colors not easily found in nature, thereby expanding the palette available to jewelers (Fig. 1). Glass-paste stones joined other reflective embellishments, including metallic threads, paillettes, and beads of every sort. A riveting essay by Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell in the exhibition catalogue describes the seemingly infinite range of glass beadwork, including sablé—miniature beads strung and stitched into pictorial elements— and jais—narrow tubes akin to bugle beads that could be sewn onto fabric, worked into trimmings, or fashioned into jewelry. Unsurprisingly, the most innovative and luxurious fashions originated in France and were exported or copied across Europe. Perhaps more surprisingly, such elaborate decoration was not limited by sex, and the fabrics used for men’s coats and waistcoats often provided a more durable substrate for sumptuous amounts of embroidery and beadwork (Fig. 7). While some embellished their garments at home, most of this work was undertaken by predominantly female professional embroiderers working within a regulated guild system. Men and women alike would have shimmered as their bejeweled bodies moved under flickering candlelight. And even if the gems were paste, the handwork required to make these clothes still signaled one’s ability to marshal monetary and human capital.

Glass has always been a global material. At various points in history it was made in, among other places, China, Egypt, Japan, and the Roman and Persian Empires. International diplomacy guided the movement of craftsmen and finished goods. In Europe’s quest to re-create Chinese porcelain, some British makers incorporated ground glass into their clay to emulate true porcelain’s translucence, while others simply used opaque white glass and called it “mock china.” Glass was one of the luxury goods involved in the expanded trade between China and Britain in the eighteenth century. Items like reversepainted glass—often based on Western print sources—traveled from the ports of Canton and Manila across the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans to England, where they were deployed into the homes of the nobility and gentry (Fig. 5). Akin to how earlier generations treated porcelain vessels, these pieces of imported glass were set into gilded surrounds that literally framed their exoticism in terms of local taste while simultaneously affirming their preciousness as trophies of Britain’s expanding commercial empire. The complexities of empire lurk under the surface of glass, and the medium’s transparency makes them readily visible. Glass emulated gemstones obtained through plunder or trade with foreign powers; whimsical table decorations were crafted from sugar—or glass made to resemble sugar—originating on plantations in England’s Caribbean colonies; and glass was incorporated into furniture made from mahogany trees felled by enslaved laborers. The scholar Kerry Sinanan reveals the interconnection between slavery and glass in a noteworthy essay in the catalogue. Sinanan draws the reader’s attention to glass beads, which were made in profusion in Venice and exported across Europe with little fanfare yet became central to the African slave trade. Contemporary accounts written by Europeans attributed the popularity of beads to a patronizing misconception that Africans delighted in such cheap trinkets. More accurately, Sinanan notes, beads had artistic importance and economic value within numerous African cultures, and as a result, Venetian glass beads became desirable, imported luxury goods that British traders eagerly offered in exchange for human bodies. Some commercial ventures in slavery were recorded in glass. A magnificent goblet (not included in the exhibition or publication) made around 1762 and signed by the enamelist William Beilby— likely to commemorate the birth of the future George IV—was lavishly decorated on one side with the royal arms in enamel.3 The opposite side depicts the ship Prince George under the phrase “Success to the African trade of white-haven.” The goblet is an important document of English glassmaking as well as a potent reminder of the wealth the slave trade brought to England’s coastal towns and to the crown itself.

Glass supported abolitionism as well, as Sinanan illustrates with a series of pressed-glass seals made by the cameo maker William Tassie and based on Josiah Wedgwood’s design of a kneeling, chained figure surrounded by the motto “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” (Fig. 6). Wedgwood’s image was the most visible abolitionist symbol of the early nineteenth century, disseminated through versions in ceramic, metal, and glass into households on both sides of the Atlantic.

If the superficial smoothness of polished glass— that attribute of beauty so lauded by Edmund Burke—seems at odds with the rougher, unsavory aspects of empire, they were all part of a single multi-faceted world. As exhibition curator Christopher Maxwell observes: “The success of international mercantilism and colonial expansion brought a plethora of new commodities to the market—consumable, material, and human. Arriving in a climate of increasing industrialization, technological advancement, and scientific inquiry, these wares were joined by a multitude of innovative British-made goods conveying modernity, pleasure, and sociability.”4

In Sparkling Company: Glass and the Costs of Social Life in Britain during the 1700s is now scheduled to go on view at the Corning Museum of Glass in May 2021.

1For the various sources of lead glass in England, see Dwight P. Lanmon, The Golden Age of English Glass, 1650–1775 (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2011), pp. 26–34. 2Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757; repr. London: J. Dodsley, 1787), p. 213. 3Lanmon, The Golden Age of British Glass, p. 42. 4Christopher L. Maxwell in In Sparkling Company: Reflections on Glass in the 18th-Century British World, ed. Christopher L. Maxwell (Corning, NY: Corning Museum of Glass, 2020), p. 15.