How did they make that? It’s a question that often comes up when looking at a work of art, especially ones that don’t fit neatly into our traditional definitions. Thanks to a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, the American Folk Art Museum has hired Brooke Wyatt, an assistant curator whose first exhibition at the museum, Material Witness: Folk and Self-Taught Artists at Work, addresses that very question—and the layered nuances it encompasses. She writes:

Material Witness focuses on the raw materials artists in AFAM’s collection chose to work with. The exhibition considers that artists not only manipulate their materials, they also learn from them, and so it expands our thinking about how self-taught artists hone their practices.

My interest in artists’ material choices and working process is grounded in the experiences that led me to art history and museum studies: working as an artist, art teacher, and mental health therapist. From the time I began working in museum and nonprofit art spaces, I felt keenly aware of the embedded hierarchies between art-world “insiders” and “outsiders.” Seeing how closely these patterns of marginalization and disregard echo the structural inequalities built into our society, I began to wonder how I could combine my passion for social justice with my knowledge of art making and art history. As an “insider” to the art world and its institutions, I yearned to connect with art and artists beyond the art world and its conversations.

After pursuing an MFA degree in painting, I went back to grad school for counseling psychology, and worked as a therapist with children, youth, and families and also in psychiatric hospitals and detention centers, often using art therapy interventions. From this work, I began learning about how systems—managed healthcare, criminal justice, health and human services, education—despite the hard work of many, too often pathologize suffering and impact people’s lives in ways that limit their agency and autonomy.

I brought these concerns with mental health, self-expression, and identity with me when I returned to academia to pursue a PhD in art history at the University of Pittsburgh. My study of the work of artists whose training and life experiences defy and exceed conventional fine art categories informs every aspect of my work at AFAM. Material Witness is an effort to foreground the contributions that self-taught artists have made at the level of material engagement and working process to the past, present, and future of what we understand as art.

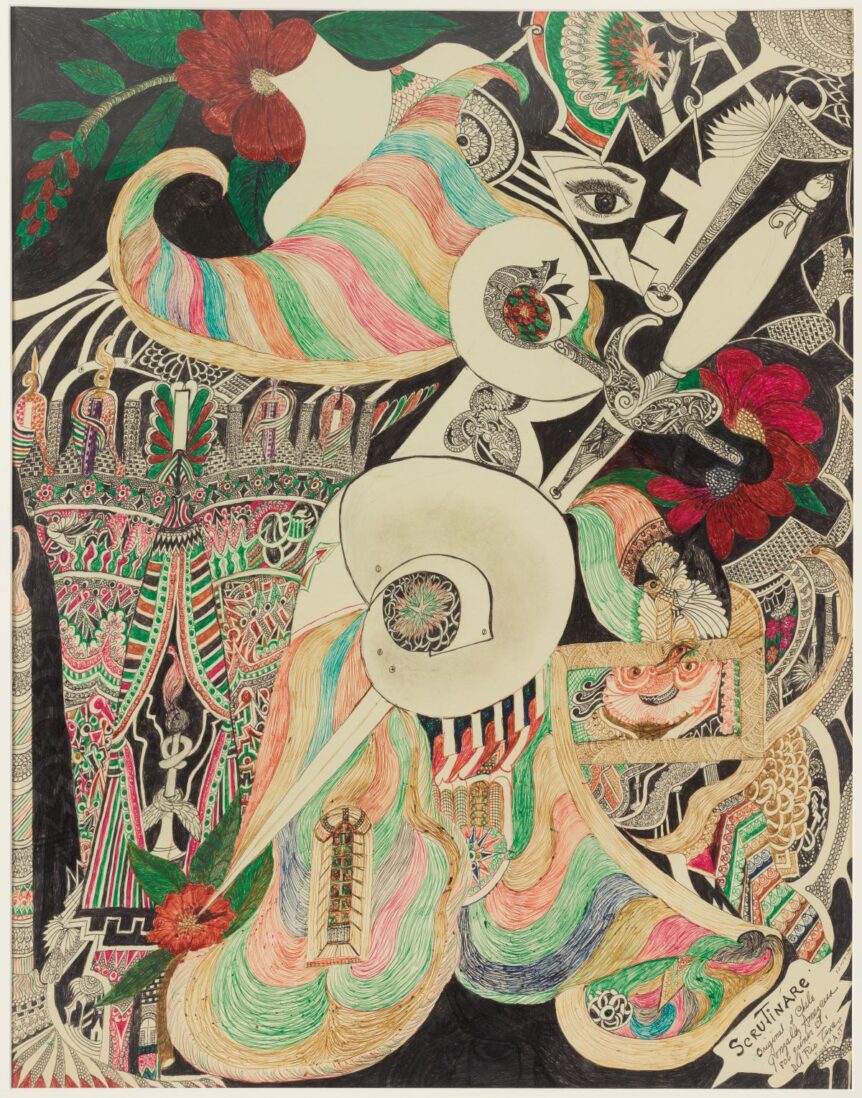

A work from the exhibition like Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua’s Scrutinare epitomizes the idea of an artist building up a deep working knowledge of their chosen materials. Also a poet and dancer, Chelo developed the intricate style of linework she called “Filigree Art” using everyday materials such as pencil and ballpoint pen. In Scrutinare, she used line after ballpoint line to create an elaborate architecture of cascading swirls punctuated by evocative imagery. Details like an embellished sword seem to pierce this labyrinthine tapestry, while the image of a human eye dissolves the tension between foreground and background. Looking closely, you can follow the traces of the artist’s hand where the imprint of each pen mark has been pressed into the paper.

Material Witness also invites study of the ways that artists’ processes evolve across time. Observers of Judith Scott’s process, for example, will recall her approach of surrounding a cache of everyday articles—a doorknob, plastic tubing, even a shopping cart—with yarn and other fibers in a method of wrapping, weaving, and knotting. Between 1987 and 2005, she created nearly one hundred such sculptures at the Creative Growth Art Center, which has been supporting the work of artists with developmental, intellectual, and physical disabilities since 1974. Out of the multitude of materials she had access to there, Scott gravitated toward the yarn, fabric, and textiles that became essential to her working process.

Material Witness, with its many insights into the trials and triumphs of “outsider” artists at work, remains on view until October 29. We look forward to what Brooke Wyatt’s unique experiences and background will bring to her next exhibition at AFAM.