Some American women and Blacks voted as early as 1776? Who knew? Some historians, of course, but it comes as a bit of a surprise for many of us, especially given the numerous recent celebrations of the hundredth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment enfranchising women in 1920. The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia explores this critical moment in a fascinating exhibition, When Women Lost the Vote: A Revolutionary Story, 1776–1790, on view until April 25 and in an impressive online version available at amrevmuseum.org. Rather than summarize the story told so well there, we asked Philip Mead, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs and chief historian, to expand on some of the reasons behind, and takeaways from, the exhibition. He writes:

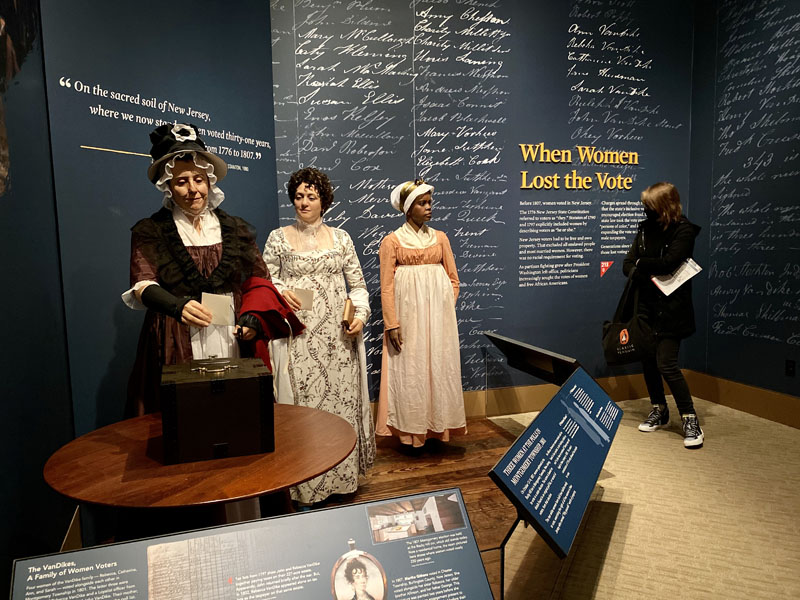

Like many other institutions, we wanted to mark the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment with a special exhibition. In New Jersey, the state’s constitution of 1776 enfranchised both women and people of color, but the legislature stripped the vote from both groups in 1807, while also eliminating the property requirement for white men. So instead of asking how women won the vote in 1920, we decided to ask why some women and people of color had it and lost it more than a century earlier.

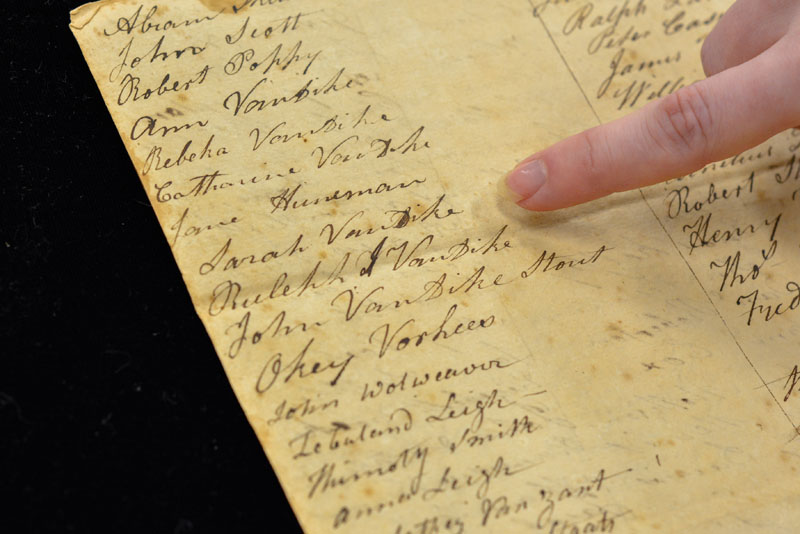

An early challenge was documenting that women and Blacks actually did vote. Marcela Micucci, our curatorial fellow in women’s history and the exhibition co-curator, began searching for poll lists in historical societies, libraries, and archives all over New Jersey, unearthing an 1801 one for Montgomery Township in the state archives that included the names of forty-six women and four Black men out of a total of 343 voters. We subse- quently identified nine more poll lists from four townships and a total of 163 women’s names out of about two thousand voters. The identities of people of color were harder to establish, because voters were rarely identified by race.

One of the most exciting aspects of our research was recovering the stories of individual voters who have otherwise been basically lost to history. In one case, our curator Matthew Skic was able to link a circa 1805 portrait miniature of Martha Githens of Chester Township to a woman on that township’s list of voters in 1807. I still have the email with Matt’s subject line: “WE CAN NOW LOOK UPON THE FACE OF ONE OF AMERICA’S FIRST WOMEN VOTERS!” We would love to hear from the current owner!

It has also been really exciting to locate and visit the graves of some of these early women and Black voters. We have placed a wreath with a “She Voted” or “He Voted” ribbon across it at each plot we visit. Wouldn’t it be nice if that became a widespread way to identify these early voters all over the state?

Overall, I think the most important message of the exhibition is that the struggle for the vote continued after 1807. Some of the daughters of the women who lost the vote that year grew up to see the emergence of the suffrage movement in the United States, while some of the Black Americans who lost the vote in 1807 saw the Reconstruction Amendments end legal slavery in the United States and prohibit the exclusion of the vote based on race.

That said, we on the curatorial team have often remarked, over the past year in particular, that we felt like we were living in two messy election cycles as once. There were so many parallels between 1807 and 2020—the controversies over who decides what is a legal vote, the partisan anger, the role of the press, the differing polling practices in a decentralized voting system. It sometimes makes me wonder how we can still be dealing with so many of the same problems as 213 years ago. But that’s democracy, I suppose. It may be a messy form of government, but, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, it’s the best we have.