It is tempting to believe that all the nations of Western Europe belong to a common culture and that each nation had an equal share in creating it, whether in literature, music, or the visual arts. That the latter proposition was never true, however, is borne out in a fascinating new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. Through more than one hundred objects and works of art, including paintings, engravings, tapestries, and sculptures, the show offers a compelling account of Britain’s visual art at the dawn of the modern age.

England’s literary achievement during the reign of Elizabeth I speaks for itself: even if we remove the transcendent Shakespeare from the equation, Marlowe, Sidney, Spenser, and Ben Jonson—to say nothing of a dozen other worthies—easily rival any writer on the Continent. But at the very moment when they were creating their immortal works, the Sceptered Isle remained, in terms of visual culture, a pallid backwater, its artists struggling to keep pace with those on the Continent. Pietro Torrigiani, Hans Holbein the Younger, and Antonis Mor—the foremost artists in England from the accession of the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, in 1485 to the death of the last, Elizabeth I, in 1603—came, respectively, from Italy, Germany, and Holland.

To admit this deficiency in no way denigrates the art of the Met show. Seen in this light, it becomes, if anything, even more interesting. But its pre-eminent charm consists precisely in its marginality, its striving for relevance even as it stands at the peripheries of Europe, looking in. England’s relation to Italian mannerist painting—by far the dominant artistic influence on the Tudors—recalls India’s embrace of Hellenistic sculpture around 200 AD, or the effects of the Spanish baroque on the arts of eighteenth-century Mexico and Peru: the very waywardness of the results, the partial and imperfect assimilation of a foreign influence, has its own potent appeal.

This marginality was hardly a foregone conclusion. Architecturally and sculpturally, England’s Romanesque cathedrals—though influenced by the Norman conquerors—easily overshadowed the contemporary buildings of Paris and its environs. Two centuries on, England’s Decorated Gothic architectural style responded magnificently to the Rayonnant style of France, just as its sober Perpendicular style, one century later, held its own against the Flamboyant Gothic of the Continent. Even during the period covered by the Met exhibition, Nonsuch Palace and Burghley House (Fig. 2) rivaled the chateaux of the Loire that had largely inspired them. In each case, a rare beauty emerged from the collision of a strong native tradition and an equally powerful style imported from abroad.

But painting in Tudor England, unlike architecture, was defined by the introduction of an entirely alien style into what had been, for generations, a visual vacuum. No English painter of the previous century could hold a candle to Jean Fouquet of France, let alone to the great Florentines and Venetians. With few exceptions, the only artists we can name in fifteenth-century England hailed from the Lowlands, and even they were hardly of the first rank.

If you have ever dined al fresco in one of London’s many Italian restaurants, you will have an idea of the spirit in which the Florentine Renaissance arrived in England. In both cases, an attempt is made to persuade you that you have suddenly freed yourself from the mists and drizzle of Albion, that your painting, or at least your pasta, is, as John Keats put it, “full of the warm South/ Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene.” Nymphs and shepherds and Olympian gods, nude or dressed a l’antica, traipse through these paintings, past classical temples and Arcadian vales, and they look rather chilly and out of sorts.

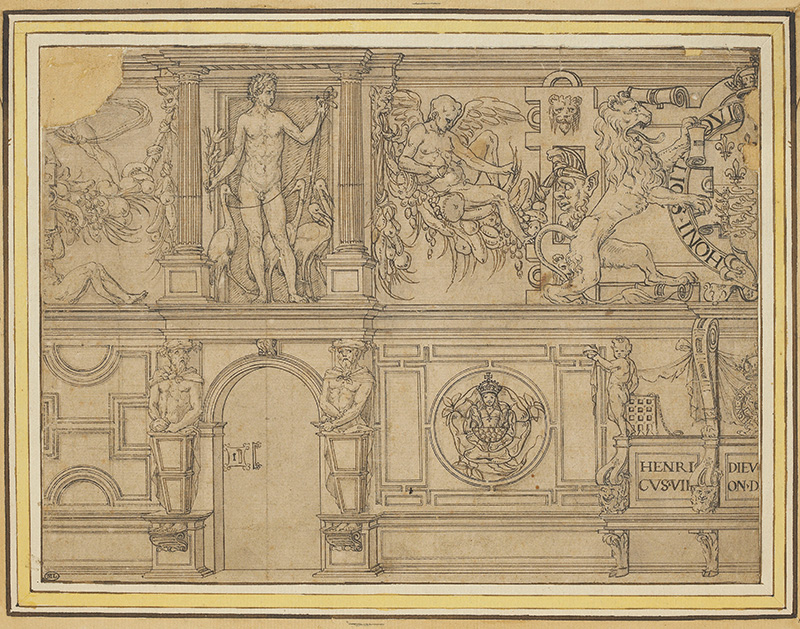

The Earl of Surrey as well, festooned in brocades, looks ill at ease amid the semi-naked deities who flank him, or the putti who float above him in a portrait possibly by an Italian artist (Fig. 3). So, too, does Elizabeth I who, in a miniature attributed to Isaac Oliver, gazes majestically upon Juno, Minerva, and Venus, the latter in all her nudity, with Cupid at her side (Fig. 4). The putti and the heroic male nude in [Two] Design[s] for an Interior at Whitehall, by the Italian artist Nicholas Bellin of Modena, carry somewhat more conviction (Fig. 5).

As might be expected in an exhibition devoted to the Tudor dynasty, there is a fair abundance of Holbeins on view. Because Holbein died in 1543, four years before Henry VIII, his great patron, it was Henry, his luckless wives, and his eminent contemporaries who chiefly benefited from this master’s unrivaled genius. Holbein was hardly above flattering his sitters. Even if the full-length portrait of the king from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool is judged to be a workshop production, it is no less magnificent for that (Fig. 6). Far more typical of the master is that probing perusal of surface that defines his portrait of the Cologne businessman Hermann van Wedigh III, from the collection of the Met.

Henry’s children and successors were less fortunate in their portraitists. True, Holbein’s delightful depiction of the short-lived Edward VI as a small child is one of the stars of the exhibition (Fig. 1). But Queen Mary (who succeeded Edward) had to content herself with the bilious, but still considerable talents of Anthonis Mor (Fig. 7), while Elizabeth I, who succeeded her, fared no better than the winsome flattery of George Gower and Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (Fig. 8).

In a larger sense, however, and despite a certain maladroitness that defines much of the art of the Tudors, the overwhelming Italianate influence on view at the Met was ultimately the means by which England made the material transition from the medieval world to the modern world. For a long time, this continental strain represented a vanguard taste: the bulk of the British nation would never see the silk and velvet brocades interwoven with silver threads that now adorn the walls of the Met, and they could scarcely imagine such mannerist extravagances as the covered cup of 1590–1591 in Figure 10, its mother of pearl body clothed in an armature of gilded silver. Nearly two centuries would pass before something of this new taste finally seeped into the homes of the humblest subjects of the crown and so ousted a persistent, residual medievalism.

During the reign of the Tudors, Italy’s artistic influence became the means by which England, rivaling Valois France and Habsburg Spain, gave outward expression—even in a borrowed language—to the new and boundless ambitions of the nation state that was then being born. The abstraction that England still was now found its physical embodiment in the illustrious, brocaded personage of Elizabeth I. But she herself is inconceivable today in any other form than what we encounter in the odd, endearing, and infinitely heartfelt images included in the present show.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from October 10 to January 8, 2023.