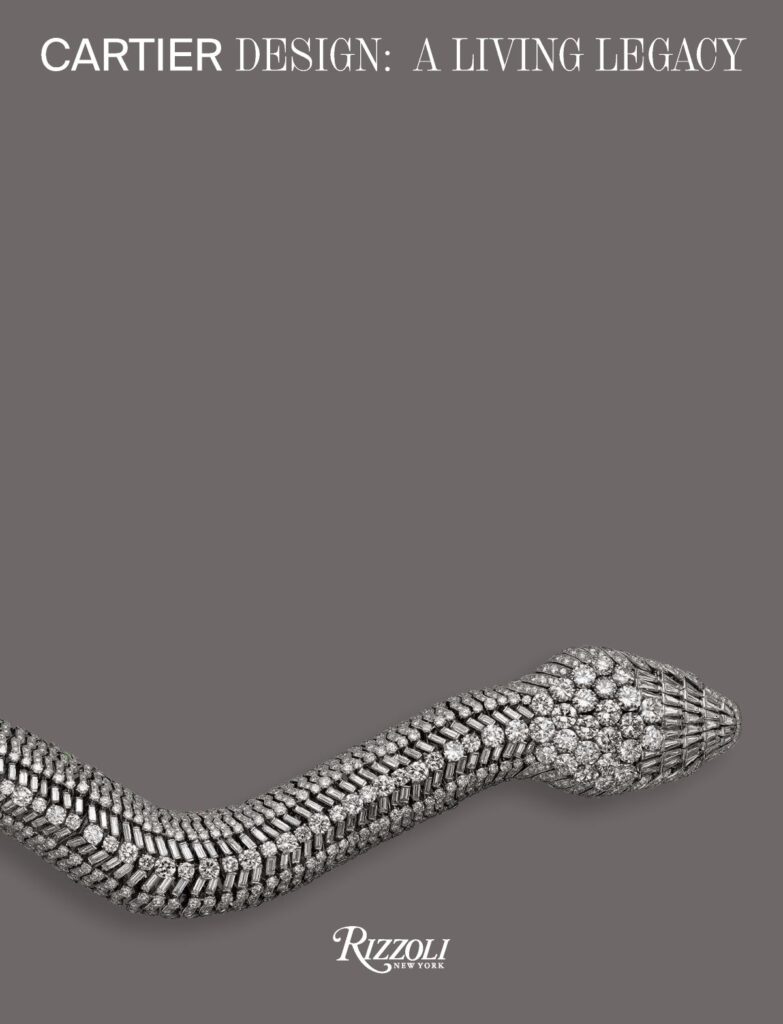

Cartier Design: A Living Legacy

When it comes to jewelry books for the holidays, there are always many that vie for attention. This year, we skimmed from the top to focus on two legacy houses of French jewelry; a New York maker of exquisite bijoux and objets d’art; and the memoirs of a longtime dealer and scholar on the international jewelry scene.

Cartier Design: A Living Legacy is the catalogue of a major exhibition held at the Museo Jumex in Mexico City this past spring. The nearly 180 works in the stately volume draw from the Paris firm’s superlative Cartier Collection, which was assembled beginning in 1983 and today contains thousands of pieces. Two women dominate the book, Cartier’s famed design director Jeanne Toussaint (1887–1976) and Mexican actress Maria Félix (1914–2002). Louis Cartier’s prescient decision in 1933 to place Toussaint in charge of design changed the trajectory of the firm, most notably with the introduction of the panther motif in the Cartier iconography. But it is the remarkable relationship between Toussaint and Félix that accounts for two of the Mexican diva’s (and the maison’s) heralded reptilian creations: the Snake necklace, 1968, and Crocodile necklace, 1975.

The fully articulated serpent is a stupendous twenty-two inches long, its scales formed by 2,473 brilliant- and baguette-cut diamonds. No surprise it required two years to make. A cunning application of red, green, and black enamel along the underside reinforces a sense of movement. Some years ago, so the story goes, Félix appeared at Cartier with a baby crocodile to emphasize that she wanted her next creation to seem alive. The resulting Crocodile necklace has 1,023 fancy-cut intense yellow diamonds and 1,060 emeralds and can be re-assembled as two bracelets. Also very much alive is Cartier’s design legacy.

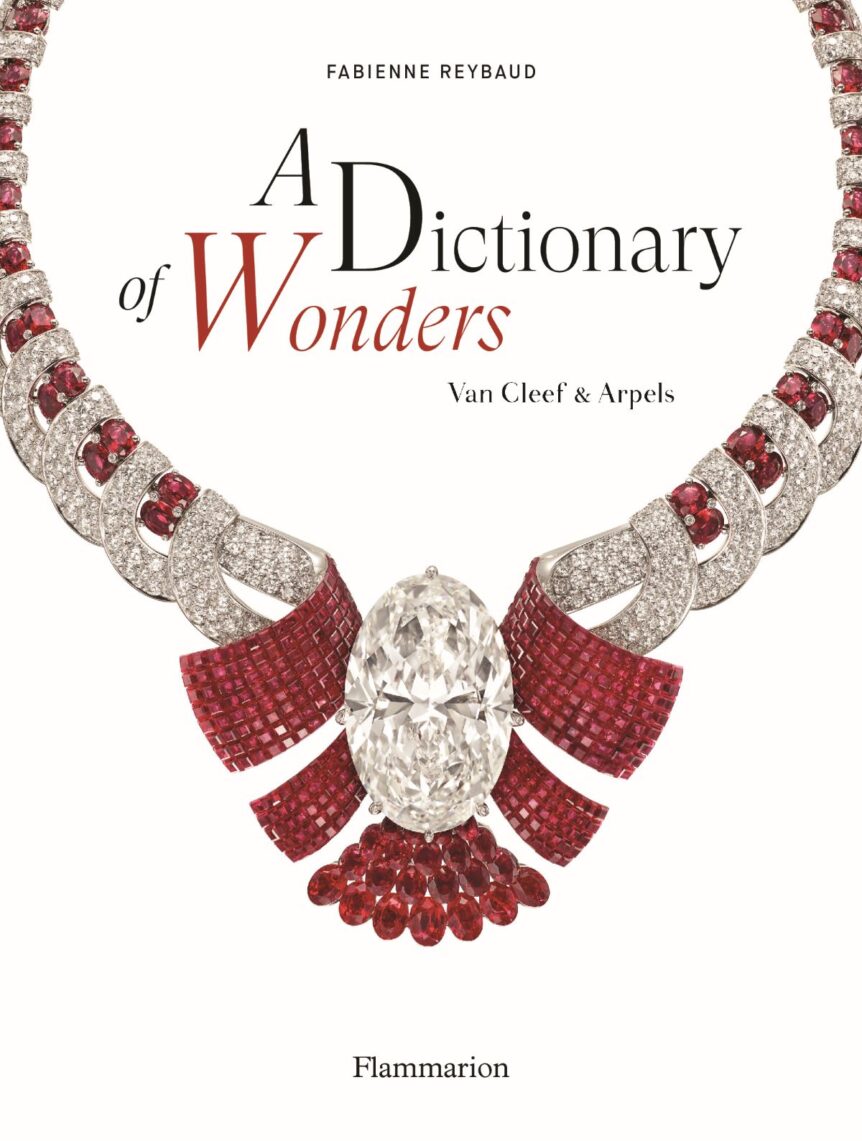

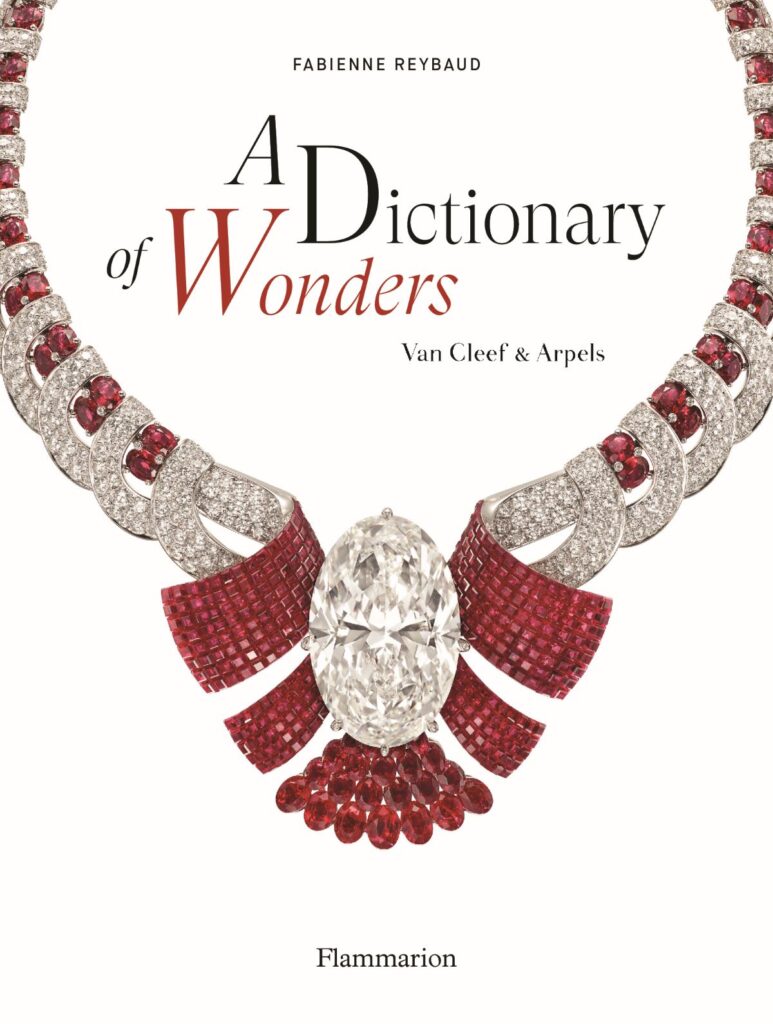

A Dictionary of Wonders: Van Cleef and Arpels

Van Cleef and Arpels has always taken a charming approach to presenting its sumptuous goods, in this case through the format of an old-fashioned alphabet primer. In A Dictionary of Wonders, the alphabet is sprinkled with terms and collection names unique to the maison, or especially prized. It would make an amusing parlor game to guess some of the entries: A for Alhambra or F for Fairy Tales are easy, but the game gets tougher when a few French phrases creep in. An especially tricky one is Pierres de Caractère under P, the name given to the high jewelry collection launched in 2006 that aimed a spotlight on the gemstones themselves.

The pleasures of the book are of course the many images of jewelry. Ballerina clips (under B), first introduced by Louis Arpels in 1941, are among the most fetching works made by the house. Shortly thereafter, choreographer George Balanchine met Claude Arpels, which inspired creations by the dance maestro—his Jewels ballet of 1967—as well as VCA’s deeper commitment to the world of dance.

The clarion message of A Dictionary really is two-fold. First, that the jeweler has enjoyed a steady engagement with the arts, and second that its bejeweled creations express the firm’s key themes: delicacy, poetry, and narrative.

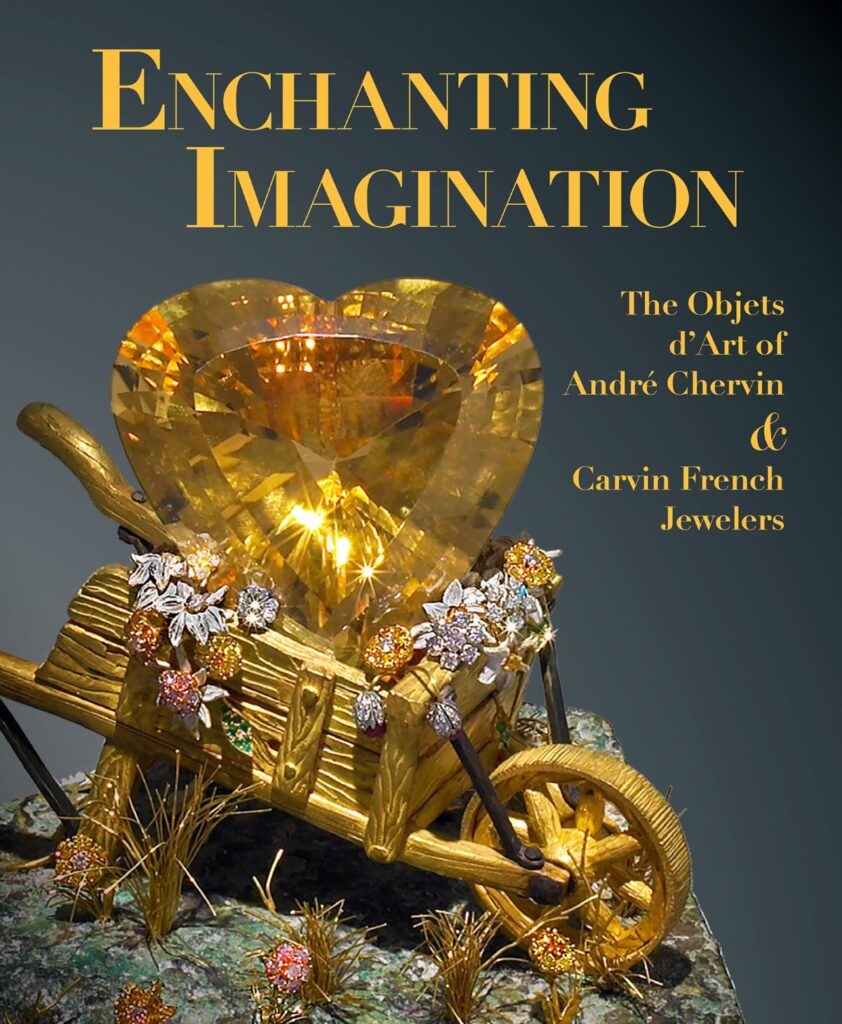

Enchanting Imagination: The Objets d’Art of André Chervin and Carvin French Jewelers

Excellence, a remarkable dedication to quality, a superb eye, and an unstinting commitment to beauty are among the many accolades I could use to describe André Chervin. He is, in a word, a treasure. After founding their New York handcrafted jewelry atelier, Carvin French, in 1954, André Chervin and his business partner Serge Carponcy went on to design and make exquisite jewelry for many of the top international houses, such as Bulgari, Asprey, and Harry Winston. Chervin is a patient man, known to take several years, if necessary, to find a gemstone whose quality measures up to his expectations. As he says, “When the material has beauty, it inspires the creation.” But for the man whose clients also included Tiffany and Company, Verdura, and Bulgari, these company-commissioned pieces came with a set of parameters that had, as its unspoken directive, “the client is always right.”

What a delightful surprise, then, to learn that when Chervin needed to let off a little steam, he turned to making objets d’art—spectacular works that rival the jewelry. Between 1957 and 2013, he and his gifted artisans created one hundred design objects, sixty of which are featured in Enchanting Imagination: The Objets d’Art of André Chervin and Carvin French Jewelers. (They are also the subject of a current exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, on view to March 17, 2024.) Several of these are small, functional, exquisite boudoir lamps, such as one made with a ruby-faceted shade. Others include Lady Ostrich, a tiny, jeweled sculpture with a plume of pearls and yellow diamonds; miniature gold boxes, about two inches wide; and the Bonsai Ornament Tree III, in gold and a variety of diamonds, gemstones, and enameling. If the above reads like a breathless list, it’s because these are works of breathtaking beauty. For decades, Carvin French has been known as “the jeweler’s jeweler,” and for those of us who are keen to see a publication of jewelry made by Carvin French, Enchanting Imagination is a rara avis. It is Chervin sharing with us his personal pleasures. “These are my own expressions,” he writes of the objects. “These are my art, pure and simple. These are my true freedom.”

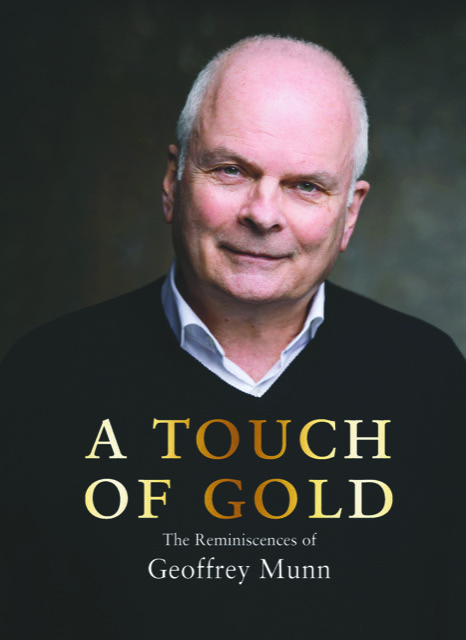

A Touch of Gold: The Reminiscences of Geoffrey Munn

Geoffrey Munn is a Renaissance man in the jewelry world. Over some five decades at Wartski, the renowned London-based estate jewelry dealer, he has come to know a lot about particularly important jewelry and particularly important people. He knows a thing or two about diamonds—especially diamond tiaras—and even more about Fabergé. He can expound on Victorian, Georgian, and ancient jewelry, any member of the British royal family across six generations, and what it’s like to be summarily dismissed by the idiosyncratic Anne Hull Grundy, one of the world’s great jewelry collectors. (When speaking with Munn for the first time, she proclaimed, “Only two really great women have ever lived. One was the Empress Catherine of Russia and the other is me!”)

In A Touch of Gold: The Reminiscences of Geoffrey Munn, stories unfold with speed, yet are full of such detail that nimble readers would do well to pace their reading and take particular aim at any number of especially rich tales. These include anecdotes about many of the jewelry-loving royals, tracking down Fabergé Imperial Eggs, meetings with, among others, Frank Sinatra, oil-fortune heir Baron Enrico (aka Ricky) di Portanova, Joan Rivers, and a collector of bejeweled dog collars. For me, however, the jewel in this crown are Munn’s accounts of goldsmith and designer Carlo Giuliano (1831–1895) and of the Roman firm Castellani. In time, his research and the contacts he turned up resulted in his first highly valued book, Castelli and Giuliano: Revivalist Jewelers of the Nineteenth Century (1984), the cover featuring a necklace owned by Princess Margaret. Munn was only thirty-one when the book was published.

Now, the man who was managing director at Wartski and a presenter on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow offers another, delightful book, one that shines a light on his many happy years in the trade. Quoting from engravings on sundials of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in A Touch of Gold, Munn says he has chosen to “Measure the bright hours only.”