Orlov-Davydov Imperial Presentation Snuffbox, made by Henrik Wigström and miniaturist Vasili Zuev for Fabergé, 1904. Nephrite, gold, and diamonds. Given by Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Count Anatalii Vladimirovich Orlov-Davydov, September 26, 1904. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Wartski, London.

The best jewelry books aren’t just costly catalogues or brand extensions; they earn their place on the home bookshelf because they enrich the taste and knowledge of the reader. Happily, a handful of recent jewelry books merit this distinction. The sumptuous Fabergé: Romance to Revolution is a scholarly focus on Fabergé’s Russian roots and its operation in London, where its only Western European shop location served aristocratic swells in Edwardian England. The storied maison Cartier looks back to history, too, but it’s not France that colors the pages of Cartier and Islamic Art, but rather the firm’s immense debt to Middle Eastern art and culture. In B is for Bulgari, the Italian house forever associated with la dolce vita serves up a light look at its New York location, opened in 1971. Finally, contemporary jewelers show off the creative power of individual artistry in two monographs: A Bit of Universe: The Jewelry of Luz Camino and Cora Sheibani: Jewels. All are worthy contenders for the library of the jewelry maven.

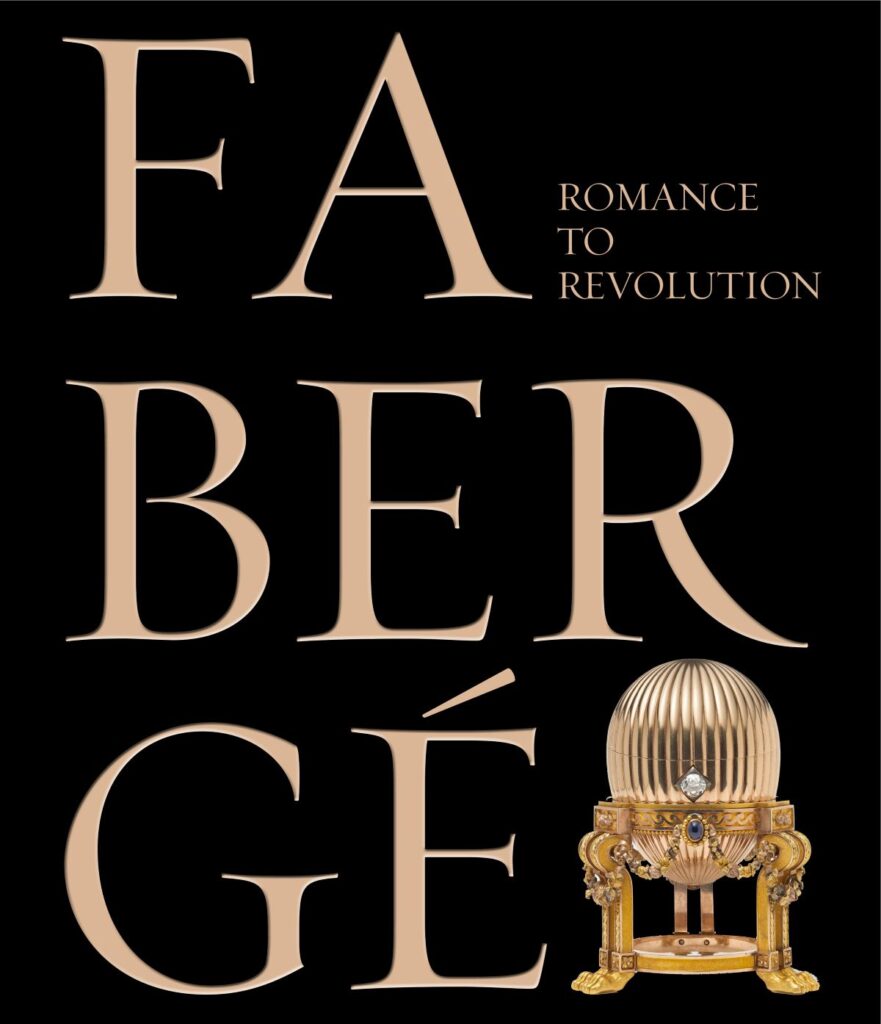

Fabergé: Romance to Revolution, ed. Kieran McCarthy and Hanne Faurby (London: Victoria and Albert Museum). 256 pp., color and b/w illus.

Fabergé. That one word evokes the very finest in jewelry: pedigree, incalculable artistry, dazzling invention, and exquisite beauty. If Fabergé always excelled at producing the finer things in life, it was well rewarded by its loyal patrons, which included various tiers of the Russian aristocracy (most notably tsars Alexander III and Nicholas II), English royals and the landed gentry of Edwardian society, and American robber barons and heiresses en voyage abroad. The citizenship of Fabergé admirers may have been international, yet they were otherwise part of a well-connected world where everybody knew one another. Fabergé: Romance to Revolution, edited by Kieran McCarthy and Hanne Faurby, deftly tells the story of the firm helmed by the singular genius of Peter Carl Fabergé. By 1900 he was the jeweler to know in Russia; that same year he exhibited his company’s wares at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where Western Europe and America saw his imperial Easter eggs and other magnificent works, giving him an expanded, international audience. Buoyed by new acclaim, vaster horizons were contemplated, with London having the distinct advantage given the royal bloodlines shared by the Russians and the British, and England’s international prowess. In 1903 the jeweler opened a shop in London, and soon was a new source (and the only one outside Russia) for the latest in bejeweled beauty. Gifts were never so grand. It was a time of heightened interest among well-heeled Londoners of all things Russian, dovetailing with a tour by the Ballets Russes, who opened at the Royal Opera House in 1911. As we learn in this striking publication, works made during the Edwardian era reflected the interests of the wealthy: their pets, horse racing, and their homes were replicated in Siberian hard stone, as tabletop silver sculpture, and on enameled boxes, gold cigarette cases, and highly ornamental picture frames. Finery and Fabergé became interchangeable.

Basket of Wildflowers Egg by Fabergé, 1900–1901. Gold, silver, enamel, and diamonds. Presented by Emperor Nicholas II to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Easter 1901. Royal Collection, © H. M. Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

Caesar by Fabergé, 1910. Chalcedony, gold, enamel, and rubies. Purchased by the Hon. Mrs. Grenville and presented to King Edward VII’s widow, Queen Alexandra. Royal Collection, © H. M. Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

Statuette of Persimmon, made by Henrik Wigström for Fabergé, 1908. Silver and nephrite. Purchased by King Edward VII October 29, 1908. Royal Collection, © H. M. Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

The story of Fabergé in London makes for fascinating reading, but equally captivating are essays about the materials, especially minerals native to Russia, the lapidary work (pigs, frogs, and rabbits among them), and of course the famed enameling process, including the bewitching guilloché technique, described in the book as appearing like “lustrous watered silk.” Things came to an abrupt stop with the onset of World War I, and by 1917 the London branch was closed. But the luxury that defines Fabergé remains its greatest legacy, along with three exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the latest in 2021–2022, for which this elegant book served as the catalogue.

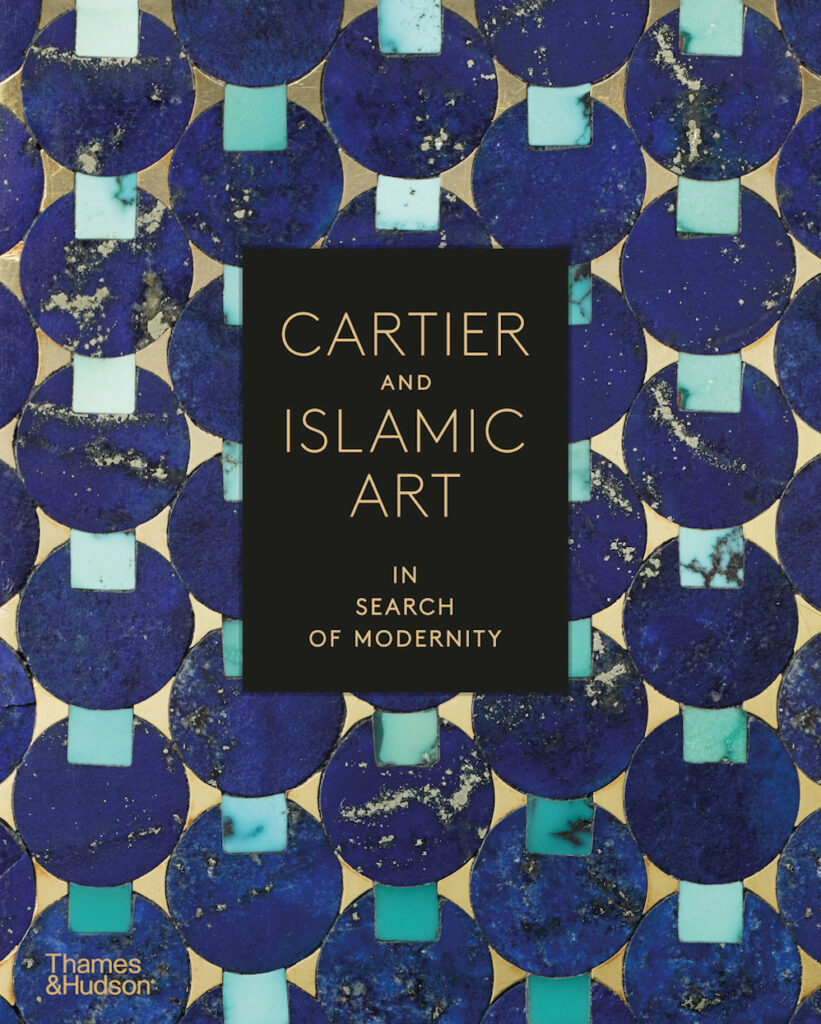

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity by Heather Ecker, Judith Henon-Reynaud, et al. (New York: Thames and Hudson). 320 pp., color and b/w illus.

In Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity, the jeweler opens its considerable archival coffers to share the story behind its most important and lasting design aesthetic. We learn how the Cartier brothers—Louis, Pierre, and Jacques—came to fall in love with Islamic art and how that became the inspiration for what we regard as the best of Cartier jewelry—the sumptuous pairings of precious cabochon or carved gemstones such as rubies and emeralds with diamonds; striking works contrasting turquoise with amethyst; and coral carved in an array of fantastical beasts and geometric shapes. (The influence of Islamic art also meant that Cartier leapfrogged the asymmetry of art nouveau and embraced the more structural forms that gave birth to art deco jewelry.)

Political upheaval in the Persian Gulf and Central Asia had resulted in an exodus of Islamic artifacts, with national treasures such as paintings, decorative objects, and illustrated Persian manuscripts now appearing in the Paris and London markets. Collectors competed to buy up these goods, among them Louis Cartier in Paris. Giving further legitimacy to these rarely seen artworks were important exhibitions of Islamic art such as those in Paris, 1903 and 1912, and in Munich, 1910, where an astonishing 3,553 works were displayed.

Bib necklace, Cartier Paris, special order for the Duke of Windsor, 1947. Twisted 18-karat and 20-karat gold, platinum, brilliant- and baguette-cut diamonds, one heart-shaped faceted amethyst, twenty-seven emerald-cut amethysts, one oval faceted amethyst, and cabochon turquoise. Formerly in the collection of the Duchess of Windsor. Cartier Collection; photograph by Nils Herrmann, © Cartier.

Vanity case, Cartier Paris, 1924. Gold, platinum, parquetry of mother-of-pearl, and turquoise, emeralds, pearls, diamonds, and black and cream enamel. Cartier Collection; photograph by Nils Herrmann, © Cartier.

In assembling this splendid publication, which served as the museum catalogue for a traveling exhibition of the same name, five major curators from the Dallas Museum of Art, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and the Louvre have written essays on the story and stylistics of the subject. The well-illustrated topics include the foundational influence of India (especially Jacques Cartier’s role in this regard); Cartier’s lexicon of forms taken from Islamic art and architecture; and, for those who love behind-the-scenes tales, the emergence of Louis Cartier’s vast collection of Islamic art. (We learn that while he was purchasing goods for the maison to use as resource material, some stock was being earmarked for his personal collection.) Cartier and Islamic Art is a magnificent book of scholarship and beauty. The skillful display of Islamic works such as manuscripts, graphics, jewelry, armor, inkwells and pen boxes alongside Cartier archival records, jewelry from the period, and recent creations is as enlightening as it is stunning.

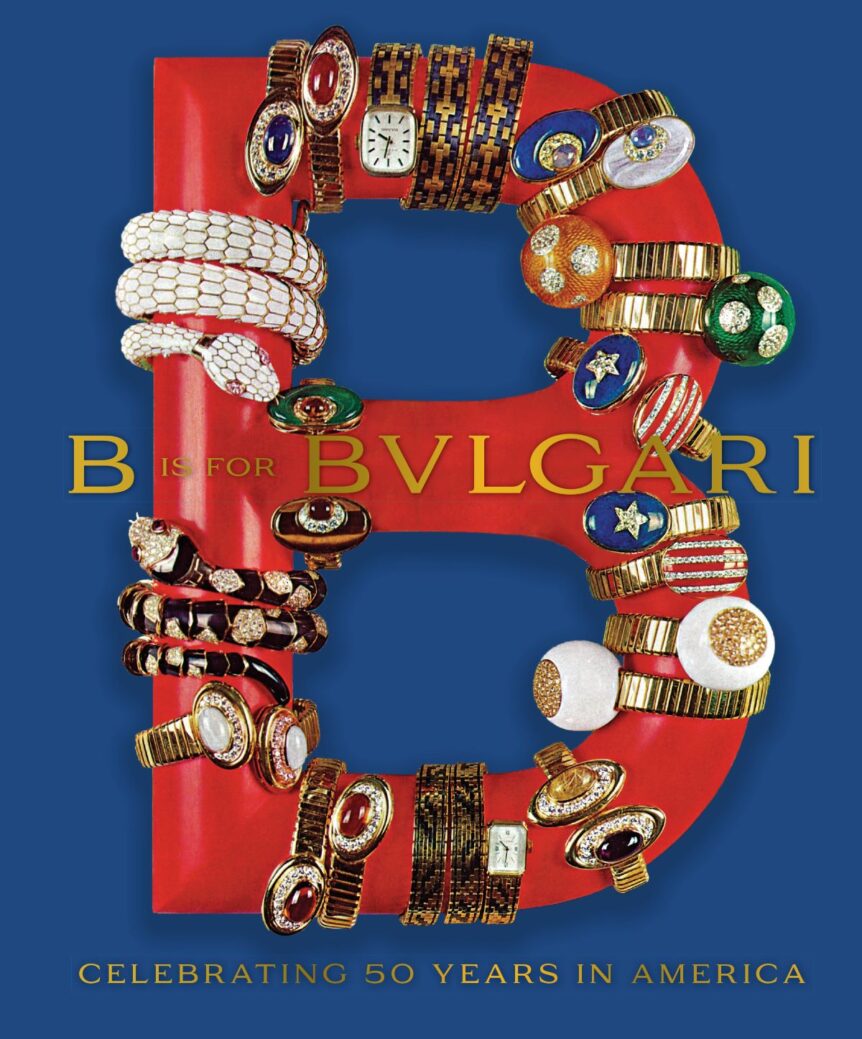

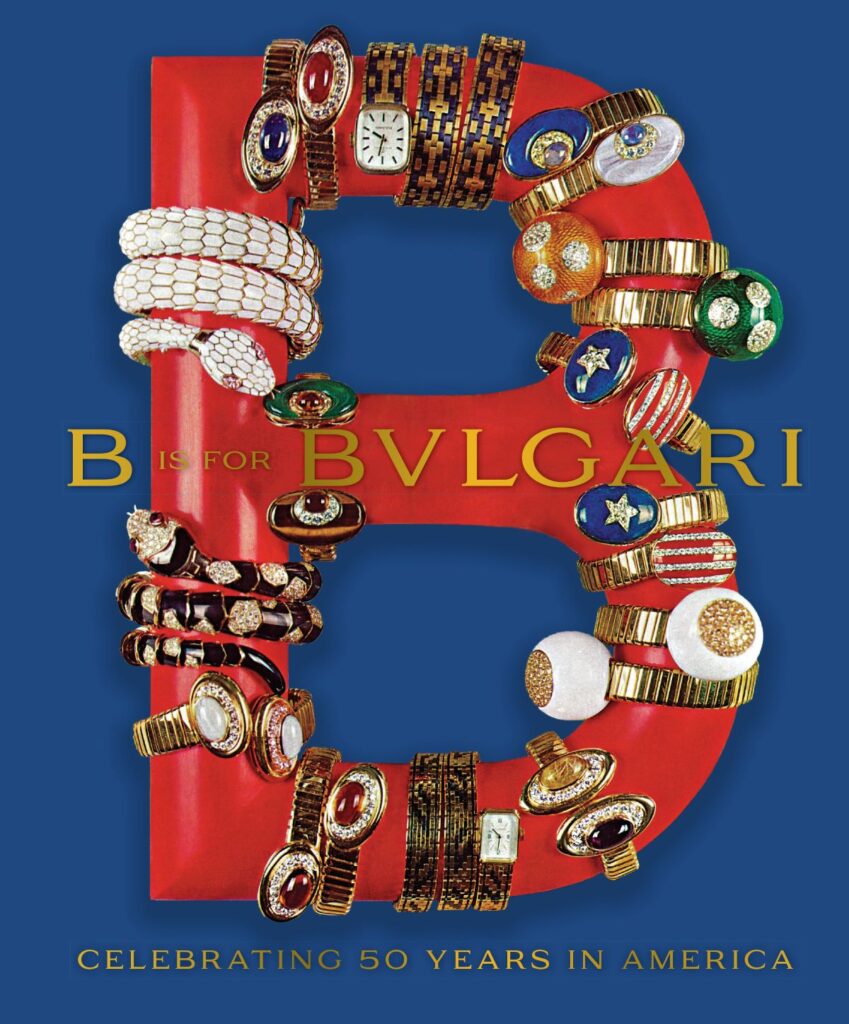

B is for Bulgari: Celebrating 50 Years in America by Marion Fasel and Lynn Yaeger (New York: Adventurine Limited Editions). 96 pp., color and b/w illus.

Necklace, Bulgari, Rome, New York Capsule collection, 2017. White gold, tanzanite, tourmaline, rubellite, and diamonds. Photograph courtesy of Bulgari.

Bulgari wears its years lightly. Since its founding in Rome in 1884, Bulgari has always embraced its past but kept its design eye on the future. “Then and now” could be its unofficial motto. From the Via Condotti in Rome to Fifth Avenue in New York, the colorful arcs of Bulgari’s many pleasures have crisscrossed the globe. B is for Bulgari: Celebrating 50 Years in America, by jewelry authority Marion Fasel and arts writer Lynn Yaeger, is an A to Z romp through Bulgari’s fifty years in New York. In their retelling of the past half-century, A is for Andy Warhol, who famously said, “For me, calling at Bulgari’s shop is like visiting the best exhibition of contemporary art”; E is for Elizabeth Taylor, whose emerald-and-diamond suite did more to promote the house than any ad campaign; N is for New York, a city as “heart-stopping as a Bulgari parure”; S is for Serpenti, the famous wrap-around snake watches made better known in books on the subject by Fasel; and Z is for Zendaya, the film and TV star whose timeless glamour (despite that she’s still in her early twenties), brings Bulgari right up to today. Bulgari jewelry is sexy, happy jewelry, doubtless fundamental to its evergreen appeal. As Gianni Bulgari, one of three grandsons of founder Sotirio Bulgari, said when describing the popularity of the jewelry, “People are looking for amusement.”

Cora Sheibani: Jewels by William Grant (New York: ACC Art Books). 228 pp., color and b/w illus.

“It’s not about obvious value” is one way Cora Sheibani has described her jewelry. And yet value is all but stamped on her many unique, stylish pieces and on the designer herself. Indeed, as made evident in Cora Sheibani: Jewels, Sheibani’s bona fides and life are inseparable from her designs. As we learn from the author William Grant, who previously wrote an excellent book on British jewelry designer Andrew Grima, Sheibani is the daughter of Bruno Bischofberger, a Swiss contemporary art dealer. It was a birthright nonpareil: she grew up in a household frequented by the likes of artists Francesco Clemente, Andy Warhol, and Julian Schnabel. (When she was just four, Jean-Michel Basquiat asked her to make a painting with him.) Postmodernist architect Ettore Sottsass, who designed a home for the Bischofbergers, wrote the text for one of Sheibani’s privately published jewelry books. Her studies included Swiss boarding schools, the Slade School of Fine Art, and New York University. This “immersive upbringing,” as Grant explains, developed “her aesthetic awareness and sense of good taste.”

An assortment of works by Cora Sheibani (1980–), from the Pottering Around collection, 2021. From left to right: Fern Earring, white gold, fossilized dinosaur bone, tsavorite garnets, green anodized aluminum; Stacked Pots ring, matte platinum, maw sit sit, custom-cut diamonds; Double Pot ring, gold, fossilized coral, spessartine garnets; Italian Pot Ring with Flamboyant Plant, rose gold, chrysoprase; Vine earring, platinum, snowflake obsidian, green and brown tourmalines. Photograph courtesy of Cora Sheibani.

The results are impressive. The Sheibani monograph deftly weaves together Sheibani’s personal life and her jewelry, exploring ways in which one feeds the other. This is jewelry as self, a propulsive narrative that demonstrably informs collections such as “Clouds with A Silver Lining,” “Cactaceae,” “Pottering Around,” “Colour and Contradiction” (one of my favorites), and “Copper Mould,” her best known and most popular collection, featuring rings topped with cake molds, pies, and ice cream cones. (If Wayne Thiebaud’s many paintings of cakes and candies make you hungry, Sheibani’s bejeweled confections dare you to bite them.) Sheibani is not only her own muse, she is also her model of choice: she appears in many of the more than two hundred photos throughout the sprightly publication.

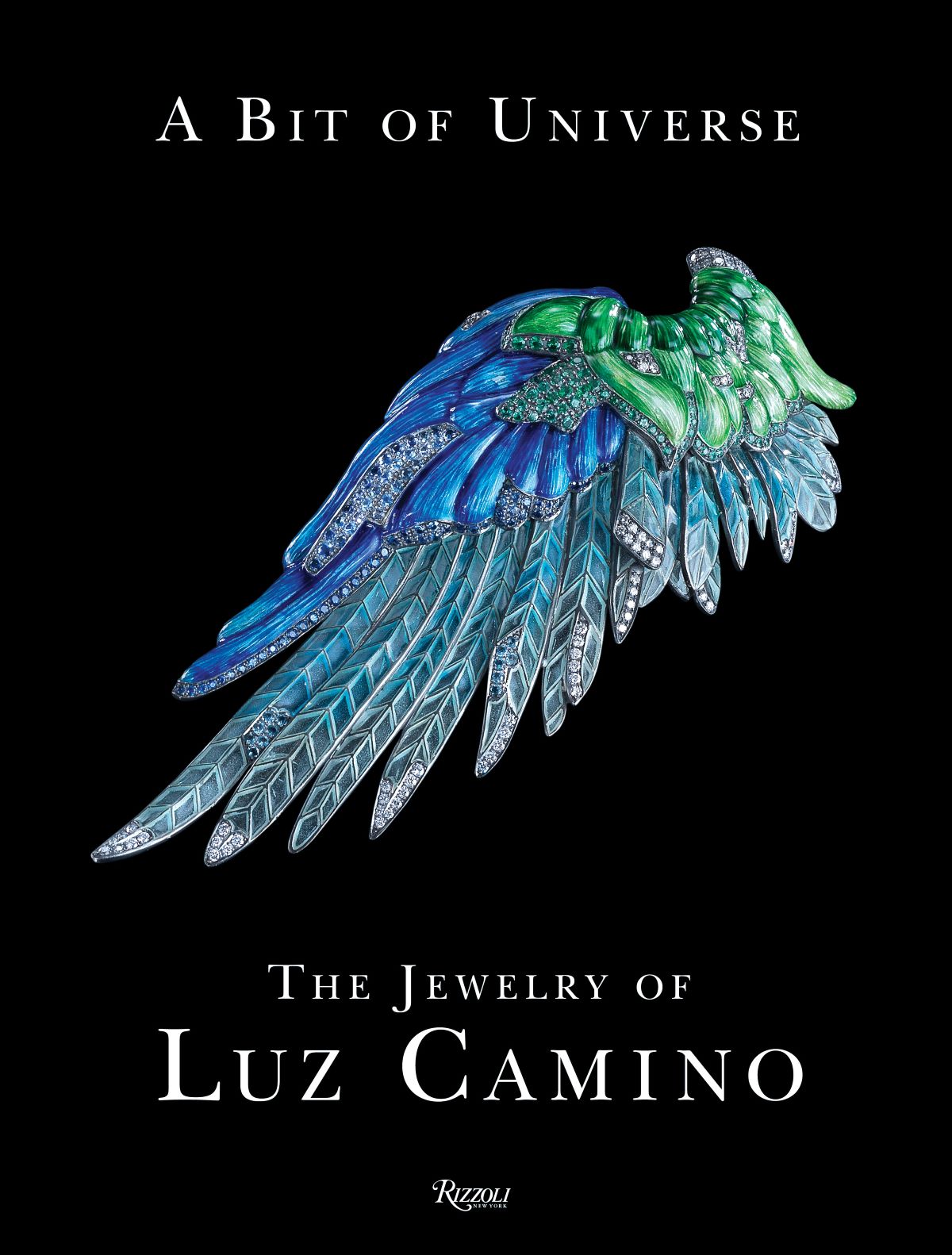

A Bit of Universe: The Jewelry of Luz Camino by Carolina Herrera, Clare Phillips, et al. (New York: Rizzoli). 224 pp., color and b/w illus.

Is English the right language to use to describe the dazzling jewelry of contemporary Spanish jeweler Luz Camino? Perhaps not. Which might also explain why in a book of 224 pages, there is scant text. Such as it is, the text includes a short foreword by fashion designer Carolina Herrera, an introduction by Clare Phillips, curator of jewelry at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and two brief afterwords—by Camino and her son and business partner Fernando Tapia. There is also an illustrated list, providing the names, dates, and materials for the 250 pieces of jewelry shown.

Bird of Paradise brooch by Luz Camino (1962–), 2001. Silver, gold, freshwater pearls, rubies, amethyst, and sapphires. Photograph by Fernando Ramajo, © Luz Camino.

The texts are just the emcees for the main event: delightful images of Luz Camino’s unconventional jewelry, broadly gathered by collection—among them, flora, creatures, and vases. Every piece has been perfectly photographed against black to dramatize the inherent magic and artistry of the works. One doesn’t just see the veining in a purple iris; one all but touches it. The cells of the orchid leaf are as fine as those by the art nouveau master of plique-à-jour, René Lalique. Nods and bows and humorous homages to other artists and other periods occur throughout: the Wink to Calder earrings are tiny mobiles for the ears, whereas the Pencil Shavings collection is another sort of wink, this time to Andrew Grima and his famous pencil shavings brooches of 1968. Camino’s moonstone jellyfish is a shout-out to Schlumberger’s famous La Méduse, a moonstone jellyfish of circa 1967. The most striking work, also shown on the cover, is also the most reverential: Durero, a sapphire, emerald, aquamarine, diamond, and enamel birdwing echoing in jewels Albrecht Dürer’s famous Wing of a Blue Roller, a watercolor of circa 1500–1512. Here is a jeweler having fun, so confident in her métier that every idea—from flowers to constellations—is within her grasp, skillfully realized in three-dimensional form. This monograph on Camino, Spain’s first female goldsmith, should help bring her wider acclaim.