I’ve been intrigued by the Florence Academy of Art in Italy for years. It’s a small, prestigious art school that revived the kind of education Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, Abbott Handerson Thayer, and George de Forest Brush had, as well as hundreds of other Americans who studied in Paris in the late nineteenth century. It’s an atelier and draws on teaching principles once used in the best French art schools but also by the Old Masters. I visited in September. There are 130 students from thirty-five countries occupying what was once an old customs house a short walk from the Arno River and the historical center of Florence. This year is its thirtieth anniversary.

Kings and queens have lineage, and so do racehorses and pedigreed dogs. Artists have lineage, too, but it’s not bloodlines, it’s all about pedagogy. Who were their teachers, and how did they learn? It’s a way of thinking and a way of making art that is handed from generation to generation. The Florence curriculum is drawn from what the school calls “the classical-realist tradition” taught most prominently by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824– 1904) and Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and by Carolus-Duran (1837–1917), who instructed his elite students privately.

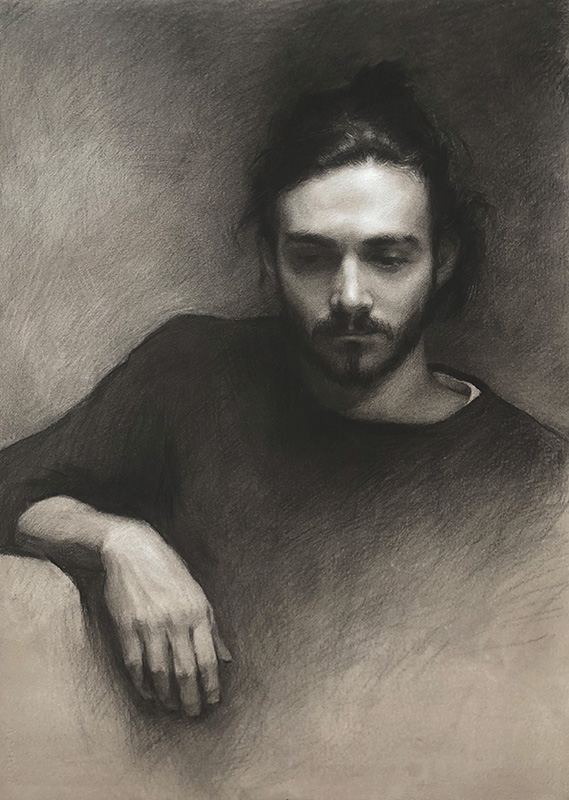

What’s old often becomes avant-garde, in art but also in teaching and learning. During my visit, I saw art of the very highest quality. Academy alumni work all over America, and I’ve seen lots of their work over the years, not often in museum shows or glossy art journals but mostly in homes and galleries. It’s different. It evokes perfect technique. The artists chase the beauty in our world. And isn’t there enough ugliness, in the world and in art?

The academy was built from scratch by Daniel Graves, an American, born in 1949, who decided to become an artist after seeing a Rembrandt self-portrait at the National Gallery in Washington when he was fourteen. Graves, with an American art school education, embraced a classicized style that led him to Italy and Florence.

He established the school in 1991 as a tiny proposition. Today, it’s an impressive complex of classrooms and studios with beautiful northern light. It confers a certificate in drawing, painting, or sculpture, and a master’s in studio art. It’s accredited by the National Association of Schools of Art and Design and is a notfor- profit 501 (c)(3) school with its own board.

The Florence Academy of Art revived the atelier system from a comatose state and near extinction. It’s an intriguing, satisfying niche. I’d call it a beacon of substance amid plenty of diffusion and sparkle. What is the atelier system? First of all, though many of the artists trained at the academy work in a realist style, lots of them don’t. The system is a methodology that builds skills, knowledge of materials, and temperament.

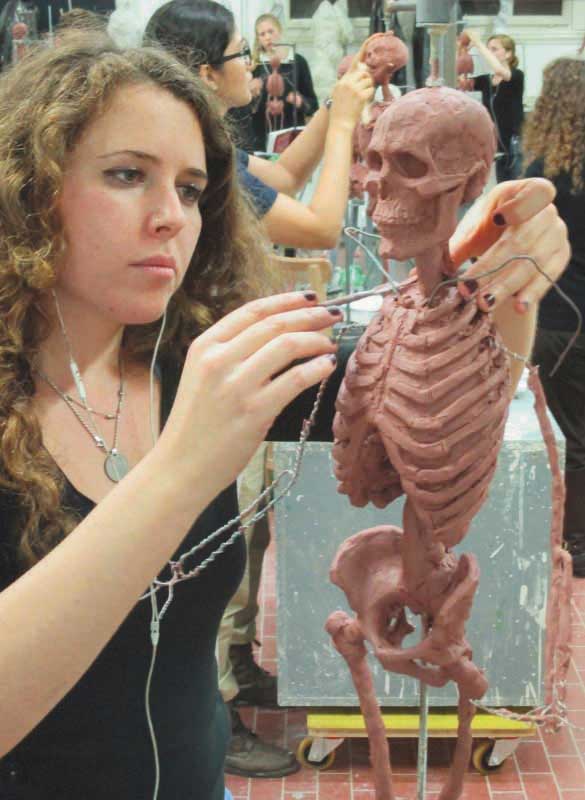

Atelier teaching and learning center on the irrefutable truths of proportion, geometry, and color harmony. Honing and strengthening the eye and the hand are vital. The foundational experience is precise and accurate drawing that conveys the objective truth of the subject. Drawing, once mastered from beginning to advanced levels, leads to painting or sculpture. Students are required to study anatomy and, for sculpture, écorché. They learn to grind their own pigments, build frames, and cook their varnishes and glazes.

There’s an essential art history component, too. The academy uses a twenty-first-century version of the instructions once used not only in the big league Paris art schools but by the Old Masters dating to the Renaissance. It doesn’t hurt to be in Florence. The Uffizi, the Pitti Palace, the Bargello, and dozens of churches and palaces, become places for teaching and learning. Students don’t learn to imitate the art of the past, and they don’t make a profession of copying what’s in front of them. They’re learning, Graves says, what the school calls “a timeless language” dating back to the Golden Age of art and architecture in ancient Greece, and using that language to tell a nuanced personal story of their own.

Over the last hundred years, the key, new movements in art drew less and less from draftsmanship, close study of the Old Masters, and a thorough understanding of methods and materials. Of greater interest were individual expression, freedom, and experimentation. These seem, practically and philosophically, to align with abstraction, and the New York school styles of the 1940s and 1950s have a long shadow. Most American college and university art schools were organized, at least in their present form, in the heyday of abstract expressionism.

The atelier system is focused and set. It isn’t characterized by abundant choice or freedom. There isn’t much room for electives, and “specialization” is limited to drawing, painting, or sculpture. Specialization is very different at today’s blue chip American art schools. I looked at the curriculum at the Yale School of Art, since I studied art history at Yale. Yes, there are semester-long classes in drawing, painting, and sculpture but foundational disciplines aren’t deeply developed. Skills, materials, drawing, and the Old Masters are dwarfed by narrow, elective courses in subjects like digital photography, typography, cinema interiors, cryptocurrency, writing and the visual arts, “Isms” and “Wasms,” and the color blue.

At the Florence Academy, intensive drawing is the seminal part of its three-year program. Students begin by copying lithographs of classical sculpture done by Charles Bargue (1826–1883) in collaboration with Gérôme. Bargue is mostly unknown today, but his lithographs were a pillar of art instruction throughout the Western world. They were used in the late nineteenth century, usually as a substitute for plaster casts but often along with the drawing of casts and live models. The goal was to train the eye and hand to convey historical conceptions of beauty with technical proficiency, to see every detail, and to learn the range of classical types.

Use of Bargue’s lithographs went completely out of style after World War I. Graves discovered a published three-volume set in the library of the Victoria and Albert Museum in the late 1980s. The books hadn’t been checked out in twenty years. The published images were, as a practical matter, a visualized lesson plan for the drawing component of the atelier method. Graves photographed some of them and started using them in his own teaching.

It’s not a program for the flaky or flighty. After mastering drawing, students can move to painting or sculpture. Students interested in painting progress from drawing in pencil, chalk, and charcoal to grisaille, learning to work with oil paint without the challenges of color. Color comes later, both the study of making color through the manufacture of pigment and how the eye processes color.

Then there are moments like the pear project. It introduces student painters to still life and was developed by Graves. Students paint a pear, first taking a few days painting in front of the object, then painting it in one session, and, finally, painting it from memory. For sculpture students, and here I can see how Eakins developed, students develop an anatomical model with bones and muscles. As with painting, though, the foundation is drawing.

Graves rediscovered the atelier system and refashioned it for today. He found disparate, thin, and worn threads leading to the old atelier system in America when he was a student. When he began his studies as a teenager, he hadn’t an aesthetic in mind, much less a philosophy about training, but soon discovered both, and they led to Gérôme.

Gérôme’s best known today as a painter of orientalist harems and Roman gladiators but he was also one of the great professors at the École des Beaux-Arts. Founded by Cardinal Mazarin, the school prepared the most promising young artists through exacting study of form and through drawing. Fragonard, Ingres, Delacroix, Degas, Renoir, and Seurat are among its many high achieving alumni.

Richard Lack (1928–2009), one of Graves’s art teachers, ran a tiny school using the atelier system. Lack had studied with Ives Gammell (1893–1981) in Boston, who in turn had studied with Edmund Tarbell (1862–1938), who adapted impressionism to American tastes, and William McGregor Paxton (1869–1941), the Vermeer-inspired portraitist and genre painter. Paxton had studied with Gérôme. Paxton and Tarbell, like Brush and Thayer, produced art that is distinctly American in subject and traditionally European in finish and correct in form and light.

At the Maryland Institute College of Art, Graves studied with Joseph Sheppard (1930–), focusing on anatomy. Sheppard developed his idiosyncratic curriculum during his own studies with Jacques Maroger (1884–1962), the director of the conservation lab at the Louvre. Maroger, who later immigrated to the United States, wrote The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Old Masters in 1948, his still-controversial probe of colors and varnishes. He, in turn, was a student of Louis Anquetin (1861–1932), the underrated French artist who was once part of the circle of van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec but veered from avantgarde French painting when he immersed himself in the work of Rubens.

Graves’s road led not to Paris but to Florence, where he studied in the early 1970s with Nerina Simi (1890– 1987). Her father, Filadelfo Simi (1849–1923), had studied with Gérôme in the 1870s. Both father and daughter ran what was then one of the last art schools in Europe to use the atelier system. It was a small school with a particular focus on the philosophy of color and classical beauty. With Nerina’s retirement, it seemed that the atelier system would disappear even in Florence, whose artists in the Renaissance saw drawing as the key to good art in any medium.

The academy still feels like a start-up. Graves is still there, as is Susan Tintori, an American, who joined the school in 1994 and runs it on a day-to-day basis, and the entire faculty are graduates, so there’s both institutional memory and commitment. Like every small art school, it’s a lift each month to pay the bills. Living on the edge makes the heart beat faster, but so does knowing you’re doing something different. If what the academy offers is very much an outlier teaching method, it’s clear to me that big American art schools should move in its direction, not vice versa.

I’m not a contrarian but know, as an art historian, that the realist vein in American art, the ruling style from Copley to, say, Sheeler, receded in prominence with the triumph of abstract expressionism. I don’t like the term “non-representational art” since every work of art depicts or projects something, however intangible. That said, abstraction, or the deconstruction and remaking of form, still rules the American aesthetic, or at least the aesthetic championed by critics, art schools, most dealers, and collectors who consider themselves sophisticated. Artists like Eakins, Sargent, Winslow Homer, and the Hudson River painters are revered as American Old Masters but not as role models for the avant-garde of our time.

As a curator at the Clark Art Institute for years, I was well aware of the French atelier system. Many of the artists whose work is in the Clark collection went through it, and the Clark has great paintings by Gérôme. Among Sterling Clark’s criteria for selecting the best art was craftsmanship, a disparaging term to creative types, but I’d call it technical brilliance, which covers Sargent’s gestural application of paint and Alfred Stevens’s precisely dazzling figures. Both had Paris atelier training.

I directed a museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, where the post-1945 collection, though a very good one, was a New York school collection. Its Pollock, Kline, Hofmann, and Barnett Newman holdings are superb, but the collection didn’t include work by Fairfield Porter, John Koch, or Rackstraw Downes, among many other Americans working in a realist style. Over time, I filled the holes, but when I discovered the Florence Academy years ago, I thought about the place realism has in today’s high-end marketplace.

The academy has taught thousands of students, and graduates have formed schools of their own, teaching via the atelier system. The working artists coming from these schools tend to occupy an economy distinct from the New York contemporary art world. I see this as a failure of conventional taste and especially in art criticism, art history instruction, and museum scholarship, all of which need to be less blinkered and less snobby and see the obvious quality this kind of teaching and learning produces.