Given the culinary focus of this latest issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES, readers are asked to imagine ordering a hot dog and receiving a bun and sauerkraut, a bit of relish and some mustard on the side—everything but the meat itself. Not only would they feel cheated, but the whole meal would seem nonsensical, a joke. This is how many viewers must have felt, around the year 1600, in the presence of such new and independent genres of paintings as landscape and still life.

Both genres had played an important role in Western painting for nearly two centuries by that point, but, crucially, they were subordinated, like a condiment, to the meat of the painting: the human form. Over the course of the previous fifty years, in the backgrounds of Brueghel and the kitchen scenes of Pieter Aertsen, landscape and still life achieved such prominence that the human figures that appeared in them seemed like an afterthought. But to remove those figures in 1550 would have been to remove the one thing that seemed to give the work its meaning and purpose.

Half a century later much had changed. In the art of Clara Peeters, a gifted painter working in Antwerp between 1607 and 1621, we finally see the newly liberated and autonomous genre of the still life in the process of being born. For her and such contemporaries as Osias Beert and Jacob de Gheyn II, the still life needs, for the first time, no justification beyond itself. But whereas Beert and de Gheyn exhibited a certain tentativeness in their compositions and perspective, Peeters, by the end of her career, had achieved a fully mature style. Her paintings, in turn, established the formal context in which, a generation later, Willem Kalf and Jan Davidsz. de Heem, with their impeccable polish and refinement, could go even further.

The emergence of the still life as an independent genre is usually thought of as a Netherlandish achievement. But, in fact, it emerged in Northern Italy earlier than in the Lowlands. Caravaggio’s great fruit basket in the Ambrosiana in Milan dates to about 1599, some eight years before our earliest work by Clara Peeters; and Ambrogio Figino’s Metal Plate with Peaches and Vines may be a decade older than that. And in the course of the ensuing century, the artists of Naples and Lombardy would develop a still life tradition nearly as vigorous as that of the Lowlands. Nevertheless, we continue to associate still lifes—and landscapes—with the Netherlands (both English words derive from the Dutch) and the case could easily be made that no nation surpassed seventeenth-century Holland in the charm and refinement of its still life tradition.

We can only speculate why the Dutch and Flemish artists of the seventeenth century felt this affinity for what were seen as the less exalted genres. Perhaps the bourgeois society of the Lowlands was drawn to the humbleness of such themes. Perhaps the realistic, fact-based spirit of the North, ever mistrustful of the idealism of the South, delighted in the more earthbound spirit of still life. It is true that some Flemish painters, especially Frans Snyders, who worked with Rubens, conceived their works in the grand manner, with an opulence and flair better suited to the courts of Italy or Spain. But the spirit of Clara Peeters’s still lifes seems to be far more typical of her compatriots.

These are sober paintings, in which the brightly lit, desirable objects of the material world emerge from a backdrop of enveloping darkness, if not pure blackness. Earth tones predominate in Still Life With Cheeses, Artichoke, and Cherries from the Los Angeles County Museum and Still Life With Cheeses, Almonds, and Pretzels, from the Mauritshuis in the Hague (Figs. 2, 1). In both these works Peeters exploits the love that her compatriots took in observing an artist’s ability to convert the material world into the two dimensions of a flat canvas: in the grains of salt piled atop the cover of an engraved metal vessel, in the imbricated folds of an artichoke sliced down the middle, in the grooves formed by a serrated knife along the surface of sliced butter. At the same time, these images must have suggested to her countrymen the bounty of the earth. Far from the princely abundance of the South, spilling across banquet boards in obscene opulence, the still lifes of Clara Peeters bespeak the well-earned sufficiency of an industrious nation, expressed in a half-wheel of gouda, a heel of black bread, a plate of cherries, and some dried fruits and almonds.

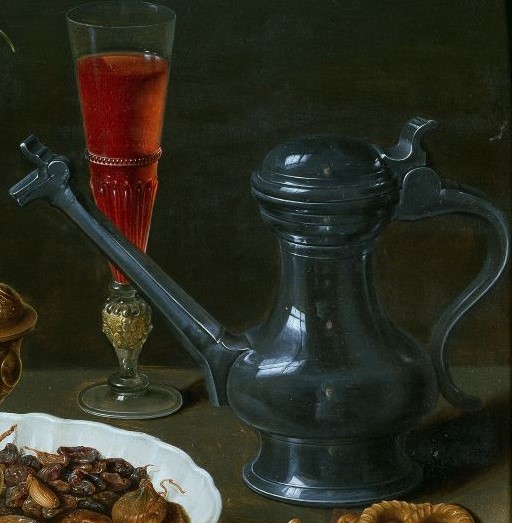

In culinary terms Peeters ranges farther afield in Still life With Fish, a Candle, Artichokes, Crab, and Prawns and Still Life With Sparrow Hawk, Fowl, Porcelain and Shells, two of her finest works, both from the Prado (Figs. 4, 3). Whether she is depicting the sinuous curves of a plated fish, a pile of crabs about to be stewed, or a group of fowl waiting to be plucked of their feathers, the same grayish greens and yellowish browns make up her demurely Calvinist palette. Only occasionally, in a work like Still Life With Flowers, a Silver-gilt Goblet, Dried Fruit, Sweetmeats, Bread sticks, Wine and a Pewter Pitcher (Figs. 5, 5a), does her palette expand to encompass a bouquet of tulips, daffodils and carnations, a golden goblet and the fiery wine glowing in a Venetian glass.

But even here, one suspects that her soul is in the pewter flagon of the title, one of her most virtuosic effects of color and light. Flitting across its surface, with ghostly indeterminacy, is the painted reflection of the artist herself. This is one of several vague images we have of the painter, similarly reflected in the surface shine of the objects she depicted.

It is even possible that the figure in Woman Seated at a Table With Precious Objects (Fig. 6) is a self-portrait. In the early years of the seventeenth century, it was by no means unprecedented to encounter woman painters, but of course they were far fewer than their male counterparts, and since they were not permitted to study the nude figure, they seldom acquired the skills that were necessary for the ambitious genre of history painting. This accounts for the hesitancy in Woman Seated at a Table With Precious Objects, one of the rare examples in Peeters’s oeuvre to be dominated by a human form. Despite the sitter’s costly jewelry and lace collar, she is awkwardly proportioned and clumsily drawn. Perhaps this was to be expected. The fact that figure drawing was denied to Clara Peeters, because she was a woman, forced her to turn her talents to the humbler objects of the external world, and thus to make her most lasting contribution in the newborn genre of the still life.