The age is long past when a single portrait could immortalize its sitter, as John Singer Sargeant’s Madame X did for one shameless upstart of the purple Nineties or—the supreme example of this sort of thing—as a certain work by Leonardo da Vinci did for Lisa Gherardini, better known as Mona Lisa. An eminent example of a portrait’s ability not only to record vitality, but even to impart it to a sitter, is Paul Signac’s 1890 depiction of the French art critic Félix Fénéon, the unlikely but most welcome focus of a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. In many such instances of portraiture’s power, there is little that we know or need to know about the sitter beyond what we are able to infer from the work itself. Regarding Fénéon, however, the MoMA exhibition (which unites works from three concurrent Parisian shows from the Musées d’Orsay, de l’Orangerie and du Quai Branly) reveals him to have been a man of many parts: writer, political agitator, art collector and much besides.

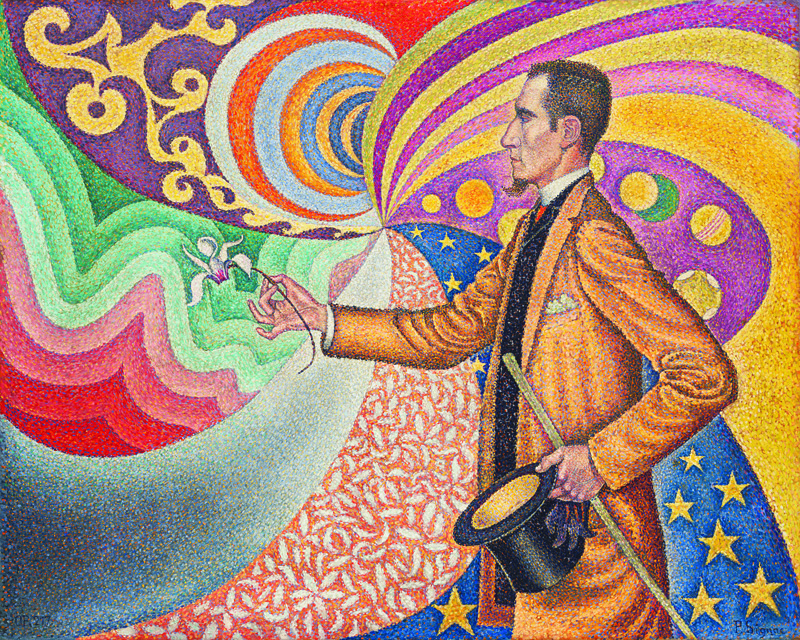

In Signac’s portrait, Fénéon rises up before us stylish and stylized in a saffron-colored coat: as a spiraling rainbow of abstract forms threatens to engulf him, he proffers a pale orchid in his outstretched right hand and holds a top hat, gloves and a walking stick in his left. Although David Rockefeller donated the painting to MoMA in 1991, it had been displayed on the museum’s walls soon after he bought it in 1947. Back then, MoMA was a far more modest affair than the Pentagon of visual culture that now dominates midtown Manhattan. But MoMA’s ability to anoint a work of art with canonic status was far greater in the largely centralized and monolithic culture of the day: to hang a painting on the Modern’s pale, unadorned walls was to gather it, by that very act, into the grand narrative of modern art. And so, for several generations of New Yorkers, Signac’s portrait of Fénéon was as much a part of one’s shared culture as if it were hanging in their living rooms.

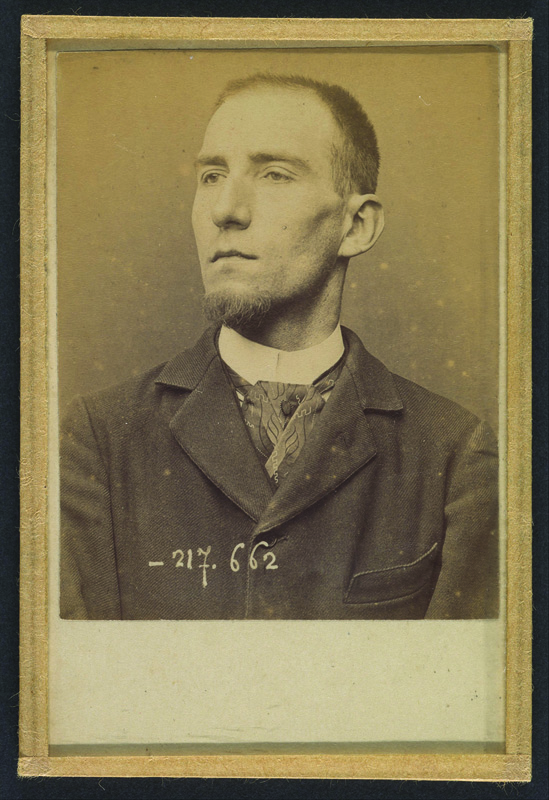

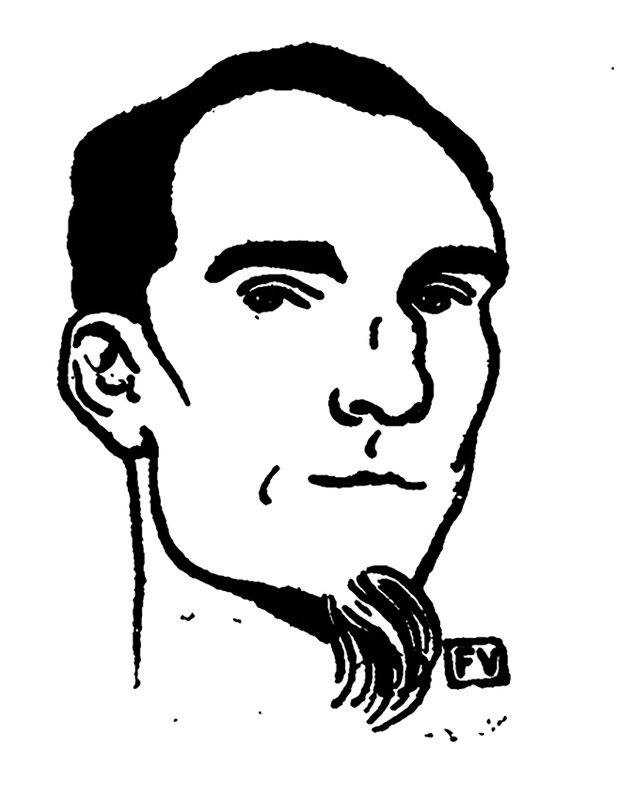

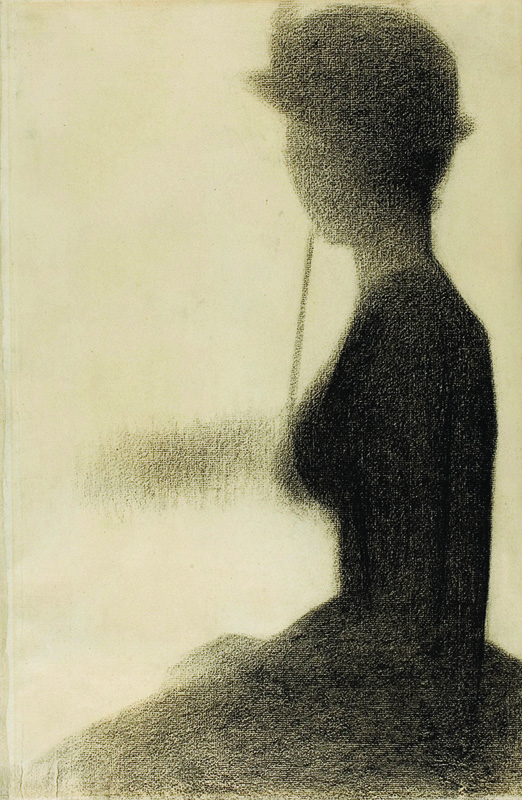

The remarkable subject of this portrait—and the person to whom the 160 other artworks that accompany it in the MoMA exhibition all relate—was born in Turin in 1861 and died on the outskirts of Paris eighty-two years later, in 1944. If Signac’s portrait depicts Fénéon in precise profile, a well-known photograph from 1894 (as well as Félix Vallotton’s woodcut from 1898) depicts him through an almost aggressive frontality. His signature goatee, more pronounced than in the painting, imparts to him something of the air of Old Nick, the devil in the flesh. Fénéon seems to represent a type that was quite new in Western culture at the time, but that would become a fixture of the century that followed: the youngish cultural provocateur, who might be an adherent of Dada, or Fluxus, or any of the punk-related art movements of more recent years. Such figures embrace the status of an outcast from bourgeois society, even as they presume to know its dirty little secrets.

Although he served for thirteen years in the War Office of France’s Third Republic, Fénéon was a frequent contributor to La Revue Anarchiste and was often under police surveillance. Suspected in the bombing of the restaurant Foyot in 1894, he was detained, along with twenty-nine others, after the assassination of the French president, Marie François Sadi Carnot, later that same year. As it turned out, Fénéon was the star of the ensuing trial, sparring with the prosecutors to such lively effect that, soon after his acquittal, he was hired by the owners of the Revue Blanche to be the editor in chief of that essential organ of post-impressionism. Only then was he finally freed from the bureaucratic tedium of the War Office. A charming painting of 1901 by Edouard Vuillard depicts Fénéon slouched over a mound of manuscripts in the offices of the Revue Blanche.

At the same time, he served as an editor of Éditions de la Sirène, where he oversaw the publication of poets Arthur Rimbaud, Jules Laforgue and Paul Verlaine, as well as James Joyce and Guillaume Apollinaire. He was also an admired literary stylist in his own right, best known today for his Romans en trois lignes (Novels in Three Lines), which he contributed to Le Matin, a daily newspaper, from 1903 to 1937. A typical example of his skills: “The swimming teacher Renard, whose students were floating like tritons in the Marne at Charenton, took to the water himself: he drowned.”

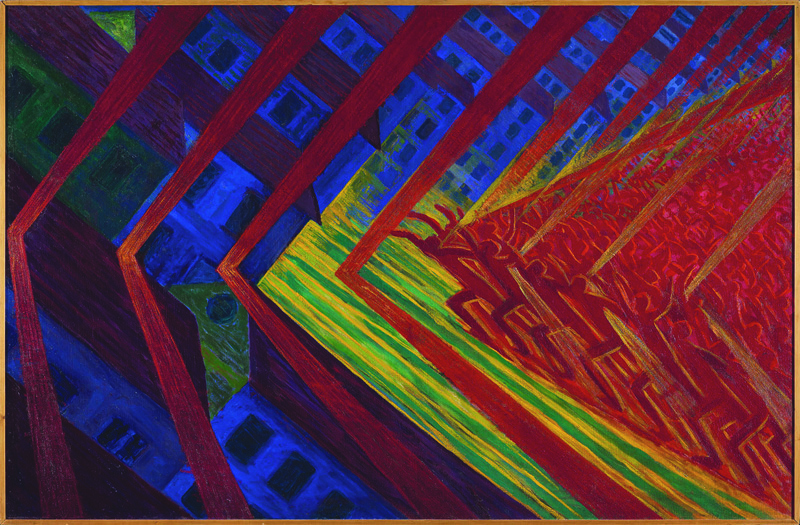

Today, however, Félix Fénéon is best known for his services to visual art. In addition to being one of the first to write about Georges Seurat, Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Signac, he amassed one of the finest collections of post-impressionism, fauvism and surrealism ever assembled. He was even a collector of African and Oceanic sculpture at a time when both fields were almost completely unknown I’m the West. When ill health compelled him, at eighty, to sell some of these works at the Hôtels-Druot on 4 December 1941, the sale included the aforementioned artists, as well as Braque, Max Ernst, Modigliani and Renoir. It was in consequence of that sale that Seurat’s early masterpiece, La Baigneurs d’Asnieres, entered London’s National Gallery, where it presides as one of the treasures of the British nation.

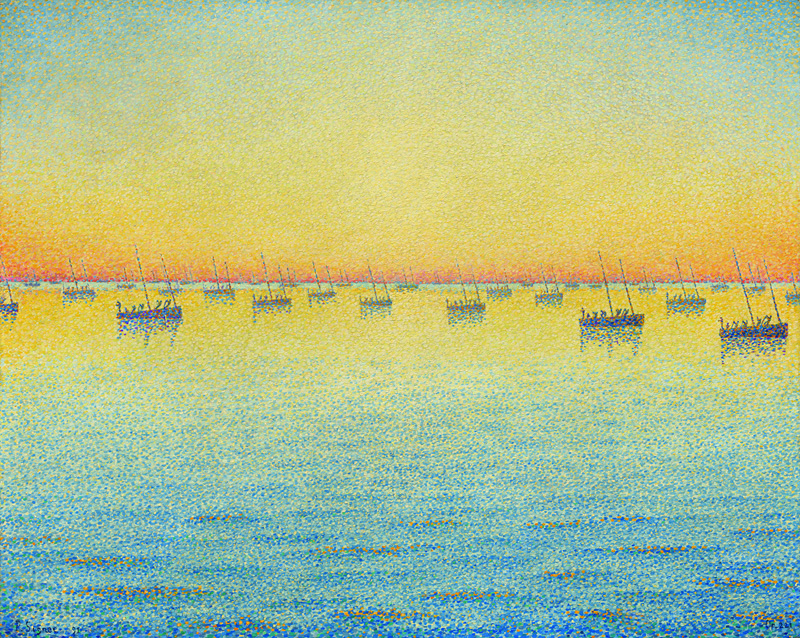

Only a few years later, after Fénéon and his widow had passed away, David Rockefeller purchased the portrait that forms the spiritual core of the present exhibition. When the twenty-seven-year-old Paul Signac first displayed this masterpiece at the Salon des Indépendants in 1890, it was widely assailed by Parisian art critics, who were less inclined to look at the painting itself than to see it through a scrim of expectations that it implicitly challenged. The actual title of the work is one of the oddest in western art, so odd, in fact, as to be almost polemical: Opus 217: Against an Enameled Background Rhythmic with Measures and Angles, Tones and Tints, the Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890. That business about Opus 217 alludes to the fin de siecle pretense that art must aspire to the pure forms of musical composition (see also Whistler’s sundry “symphonies” and “nocturnes”). It is difficult to say if the title is also a joke at the expense of aestheticians like Charles Henry, a friend of both the painter and the sitter, or if it earnestly invokes their writings, which were central to neo-impressionism, the term that Fénéon coined to describe the art of Seurat and Signac. Today the movement is more commonly called pointillism or, occasionally, divisionism. The technique entails the accumulation of short strokes and points of pure color that, from a distance, gather into recognizable form. The resulting objects—in theory at least—come closer to retinal reality than art had ever come before.

But if Signac’s portrait of Fénéon is one of the towering achievements of neo-impressionism, it also reveals the theoretical weaknesses of that movement. For all its scientific claims, it never attained that deeper reality to which it aspired. Indeed, pointillism is a singular instance of a purely arbitrary set of aesthetic convictions that succeeded—briefly, but mightily—not through any compelling theoretical merit, but through the sheer brilliance of its fruits and through the purely fortuitous convergence of several artists of irrefutable genius who labored under its standard. For all its jabs and dabs of color, Signac’s image of Fénéon achieves a washed out, symbolist nuance, ethereal and shy of outright declaration. The hard contours of the observable world seep into one another with that same air of resonant fatigue that suffuses the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes—who, not coincidentally, was Seurat’s teacher. At the same time, the eye can touch as well as see, and no small part of the pleasure we take in Signac’s portrait is an almost tactile appreciation of its fine-spun surface, formed from tens of thousands of tiny squibs of color. And, yet, somehow out of those myriad atomic particles there emerges a unified figure of unforgettable presence, one Félix Fénéon, and he lives.

Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde—From Signac to Matisse and Beyond at the Museum of Modern Art in New York was originally scheduled to run March 22 to July 25, 2020 moma.org