The early history of the acquisition and display of Native American objects as emblems of conquered power is an ugly one. If its odor still lingers in heated discussions about how public institutions like museums and universities should fulfill the mandates of NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990), that is not surprising, especially since virtually everything from the teaching of phonics to ketchup on hotdogs is now polarized in some form of all-or-nothing debate. And yet, unlike twenty or thirty years ago, many museums have already seized the moment as a new generation of curators realigns institutional goals with those of source communities on questions of repatriation and other matters. It can be—and should be—a particularly fruitful moment in our history.

But while many very good things are happening across the nation, voices are still being raised, notably in a Pro Publica article this spring charging that several Native American objects in the Diker Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art “could have been stolen or may be fake,” and taking the museum to task for failing to follow the protocols of NAGPRA in quickly returning them.

I don’t have to argue the matter here since the museum has already clarified things in a Hyperallergic article by its curator Patricia Marroquín Norby (Purépecha), explaining what has made the NAGPRA process a lengthy one. Curators elsewhere tell me that arriving at a consensus with tribal experts about what should remain and what must be returned can take a long time for many reasons, as can the research and agreement to correct the information on a museum’s wall labels. When you consider that the Diker Collection encompasses art from more than fifty Native cultures, you get a sense of what a staff assigned to matters of provenance, authenticity, and repatriation is up against at even the wealthiest of museums.

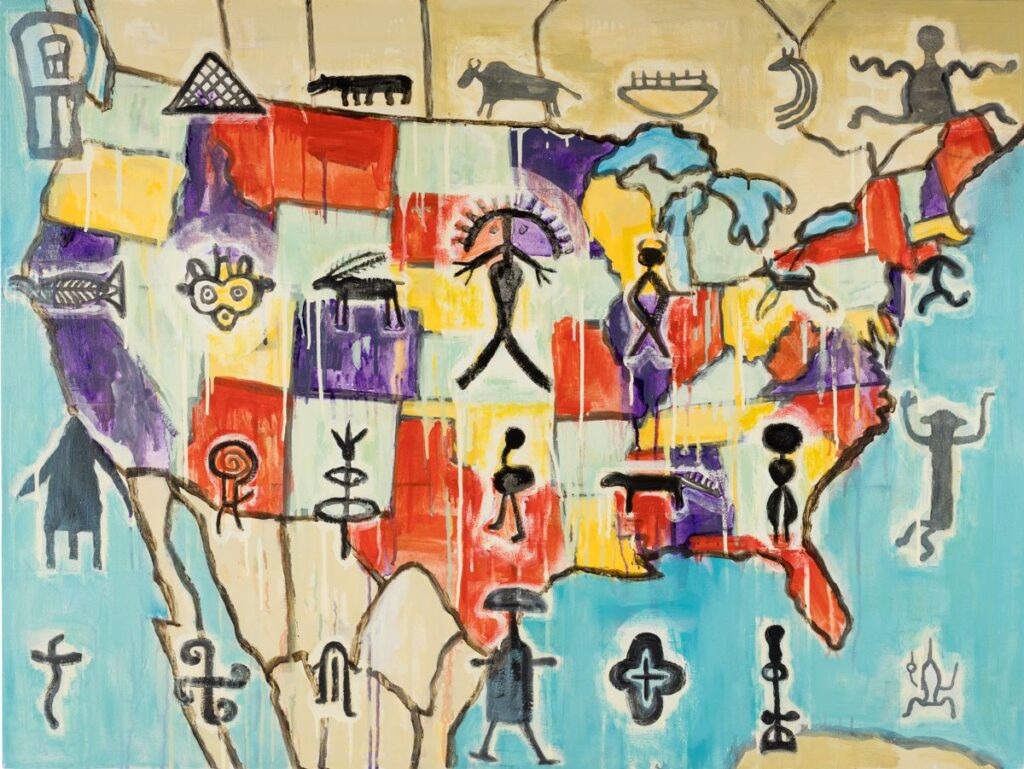

It’s a shame about the shouting because if you look around you can’t help noticing that we are in a golden moment of Native American culture—in literature, television, dance, music, but especially in art. (One of the year’s most heralded shows is the superb, revelatory retrospective of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.) Given the political and environmental challenges that Native Americans continue to face, this might be surprising, especially if you haven’t read Ned Blackhawk’s revelatory new book, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. A counter narrative to our benign national myth, it meticulously traces the “struggle, survival, and resurgence” of Indigenous people despite centuries of dispossession and efforts at erasure. For every downturn in Native American history—from Removal to Reaganomics–Blackhawk , a professor of history at Yale, presents activists who have risen up in response.

The book is not about art, artifacts, or museums, but is adept at showing readers that American history is Native American history. To that end it is especially suggestive when you begin to consider questions of repatriation, the American museum, what should and should not be on view there—and why, in my opinion, the current controversies ought to play out in exhibitions instead of going nowhere in shouting matches and gotcha articles.

A particularly difficult area for museums lies in the exhibition of the huge numbers of Native American objects that were not intended for aesthetic response—objects of obvious utility, of course, but far more challenging and controversial, objects whose purpose and power is spiritual. This is not a new problem for museums. The Africa Center in Manhattan has addressed it for decades in careful and innovative ways without, as far as I know, violating source communities, while the Museum of Modern Art’s “Primitivism” In Twentieth Century Art of 1984–1985, with its pairings of African masks and other tribal objects with modernist artworks, lives on as the gold standard for what not to do. The history of how the relevant Native American objects have been and should be seen is a rich one, and my sense is that the time is right to address it in more than one exhibition, particularly given those Native Americans outraged by what they see as the art world’s reification of the spiritual.

And while I am in the business of wishing for exhibitions, I think it might be healthy to address the vast category of Native American objects made for trade (and thus survival). After all, even the sculptor Edmonia Lewis (Mississauga Ojibwe and African American) served up baskets and beaded tourist goods in her youth, but beyond that some of the fine objects in the Diker Collection were undoubtedly made for non-Natives. Which objects? I’d like to know—and to know much more about their cultural and commercial context. There’s a long history here that many museums can and should address bit by bit, as some have begun to do.

Some of what I hope for is already happening as I look around me and see Native communities taking a major role in museum exhibitions. Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery, curated by the Pueblo Pottery Collective and presented at the Met in conjunction with the Vilcek Foundation is one example (on view to June 4, 2024). Bard College’s Center for Indigenous Studies has assembled one hundred artists to shape the exhibition Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969, which is on view to November 26. Both shows do what museums must—link historic and contemporary works in themes of continuity, survival, and triumph.

The past is now, and we are only at the beginning of what the Diker Collection has to teach us. While a few loud voices enjoy vilifying these benefactors, it is well to keep in mind that in addition to trying to be careful about provenance (another tricky subject for museums to address publicly), the Dikers insisted that their gift go to the Met’s American Wing rather than to another department, making it possible for us to see and say, as Ned Blackhawk does, that American history is Native American history and that Native American art is a significant part of that.