Recently I’ve had second thoughts about the ascendancy of the autonomous art object. Admired works, we like to think, occupy a space beyond the circumstances of their creation, beyond biography, social context, and even history itself in the exalted realm of. . . art. Often they do, and yet . . . when they both do and do not, they may have something else to say, some- thing valuable I think.

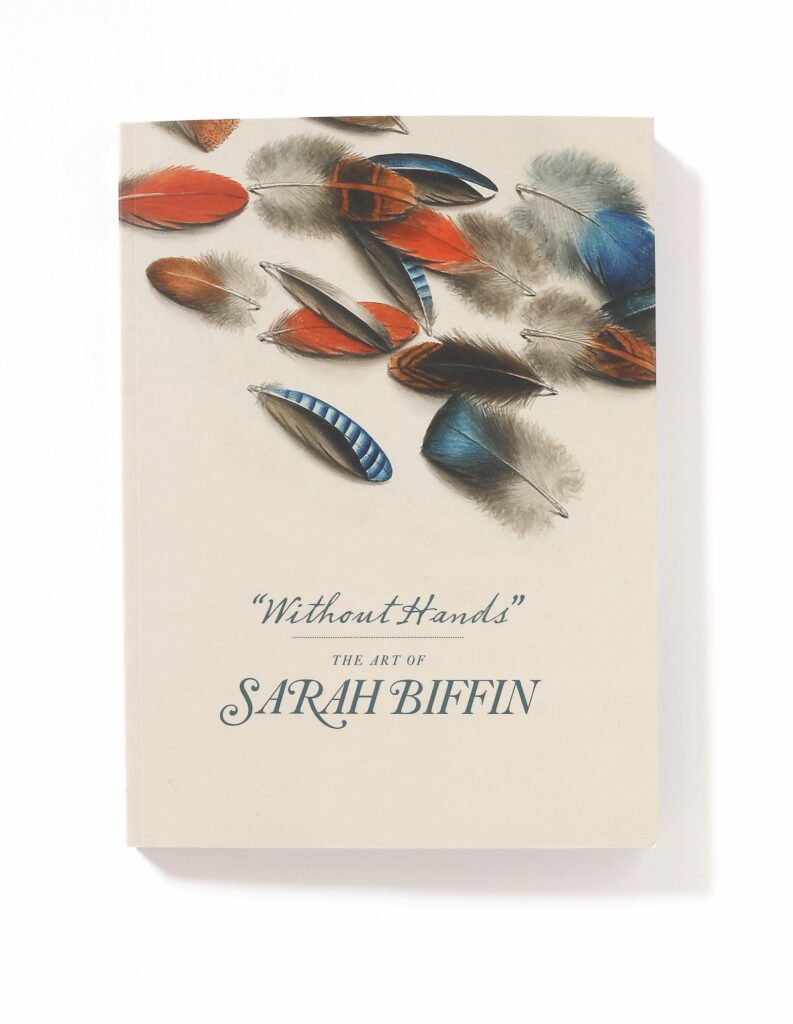

Although it had no press in this country, news of a well-received London exhibition of works by Sarah Biffin, an artist born without arms or legs to a Somerset farming family in 1784, reached me from an enthusiastic friend and neighbor in Brooklyn. Having been dimly aware of the Biffin phenomenon thanks to the redoubtable American dealer in portrait miniatures Elle Shushan, who will come into this story later, I obtained the catalogue produced by the Philip Mould gallery, “Without Hands”: The Art of Sarah Biffin.

It’s a handsome publication with solid scholarship and excellent production values, but before I got to that I was drawn to a self-portrait on the flyleaf that knocked me out. It’s a big work that nevertheless measures less than five inches high. The artist’s gaze is more bold than accommodating, her finery fashionable rather than functional, even as she presides over the tools of her trade—the needle attached to her dress, her painting slope, and her paints. Using her mouth and shoulder, Biffin was surprisingly prolific, especially in portraiture. She painted herself many times but the early ones show a far more tentative figure. She did this one in 1821, by which time she had moved beyond being freakified in fairs and taverns across the country to London, where she exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts and was poised for success, royal patronage, and marriage.

How did she do that? She had help, of course, but she more than helped herself, managing her stigma by, paradoxically, keeping the focus on it, often signing her works, “Drawn by Miss Biffin without hands.” A fine essay in the catalogue by Emma Rutherford valiantly considers the artist’s work separately from her physical disability; it’s a good and necessary exercise, but it was something Biffin emphatically did not do, making herself something of a household name with, among other landmarks of notoriety, throwaway references to her in several novels by Charles Dickens. She knew what she was about.

But what happens after decades pass and interest in the story of the artist without limbs fades, as it inevitably did, and the art shows up here and there pretty much on its own? To answer this question I called Elle Shushan, who, though far less biddable than Miss Biffin, has been no less adept at pushing past the confines of her niche field of portrait miniatures. In the late 1990s, Shushan told me, you could find a Biffin portrait miniature on the Portobello Road for a reasonable sum, maybe £500 to £700. She bought one from 1844 of the sheriff of Liverpool and later sold it at an antiques show to a woman who has since become a Biffin collector. Let’s call this woman Collector B, as she wishes to remain anonymous. When I asked Collector B what drew her to that first purchase, she answered with disarming candor, “the story behind it.” Ah, an honest woman, and an answer that was particularly gratifying for this writer.

It’s now some decades on from Collector B’s first purchase and I have learned that the portrait on the flyleaf, the one that initially drew me in, sold at auction in 2019 for more than $180,000. And so the once celebrated story of Biffin’s body has rejoined her work, making the exhibition “Without Hands” at London’s stylish Philip Mould gallery all but inevitable.

But there is more to the Biffin phenomenon to consider. After all, there were, according to one catalogue essay, two other similarly disabled American artists, rough contemporaries of Biffin, who did not even approach the foothills of her success and who, you can be sure, will not experience any resurgence of interest in their work. As I see it, Biffin’s prominence arose from the inextricable connection between the quality of her art and the way in which she managed her stigma, making her biography and her art inseparable.

Reading a few of the letters composed in her meticulous penmanship, I noticed an impressive ability to push beyond being protectively loved for her disability: “I thank god that he has been pleased to make me as I am, nor do I envy the enjoyments of others.” At the same time, Biffin inevitably prompted a radical identification with the helpless state of babyhood common to us all. (Indeed, the governess to the royal children is quoted comparing the new royal baby Princess Victoria, born in 1840, to “a blind Miss Biffin.”)

None of the successful balancing acts she managed between our identification with her stigma and our grateful distance from it was by any means a conscious strategy on the artist’s part. She simply seems to have been instinctively adept at drawing people to her while also managing situations that should have made them uneasy. An illuminating article in the catalogue by Essaka Joshua, a scholar who specializes in disability studies, clarifies the historical context of Biffin’s achievement. Among other things, Joshua underlines what we all should know about the stigmatized: acceptance is always conditional—behind closed doors things are often otherwise than sweetly appreciative. And so we find Elizabeth Barrett Browning, the immensely popular nineteenth-century poet, early advocate for women’s rights, staunch opponent to slavery, and a woman herself beset by disabling illnesses, writing to a friend that Miss Biffin was a “worse monster than any in the world.” Shocking? To Miss Biffin, undoubtedly not all that surprising.

Sarah Biffin’s art is not the transcript of her disability or the story of her successful management of it. Nor is hers a proto-feminist saga as some would have it. She was beyond category; she had to be. Her biography informs her art rather than making excuses for it and that is part of the reason I’m never giving up my admiration for that sassy self-portrait.