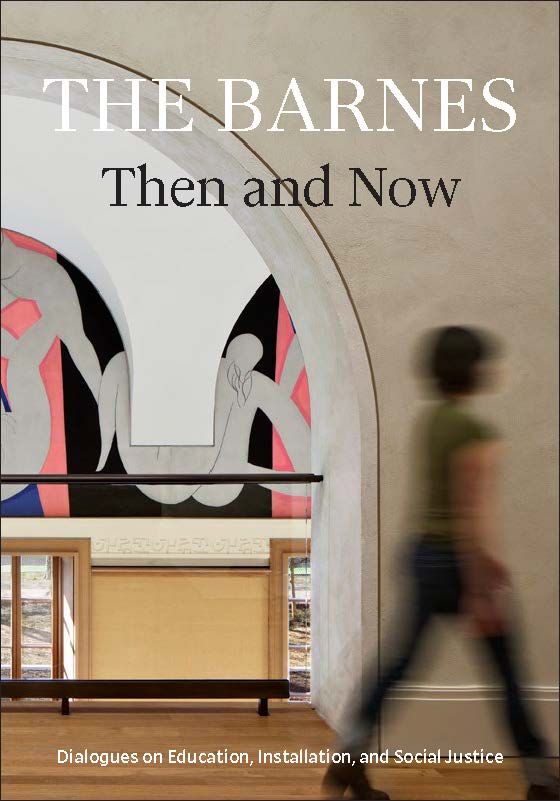

A decade or so after its controversial move from the suburb of Merion to museum row on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, the Barnes Foundation has published a book, The Barnes Then and Now: Dialogues on Education, Installation, and Social Justice. It’s a detailed and fascinating volume, bringing together contributions from outside scholars, Barnes staff members, and community activists, that begins by illuminating the foundation’s origins in the 1920s with careful discussions of the Barnes Method—Albert Barnes’s theory of art education for the masses to “improve minds and transform lives.” The next section explains his rationale for his unconventional installations, where masterpieces of Cézanne, Matisse, Seurat, Van Gogh, and so many others are surrounded by decorative arts of unknown pedigree. Part three addresses the wider issues of social justice that animated Barnes and links all three sections to the foundation’s current engagement with, and improvisations on, the original mission.

Of course, there is an unacknowledged subtext to the whole enterprise, one that will keep some readers on edge given what they know from The Art of the Steal, a widely praised documentary about the ways in which Philadelphia power brokers were able to break Barnes’s trust, subvert his mission, and move the foundation to the city he once described as “a depressing intellectual slum.” But for the attentive reader this undertow of dismay will now be accompanied, and perhaps even offset, by an appreciation of the current Barnes. Arriving at this balance is the kind of adventure I can encourage people to embrace with the help of this book (which is blessedly free of any self-justifying contributions by the political figures who brokered “the steal”) and, of course, by visits to 20th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway in a city that is now vastly different from the one Barnes disparaged.

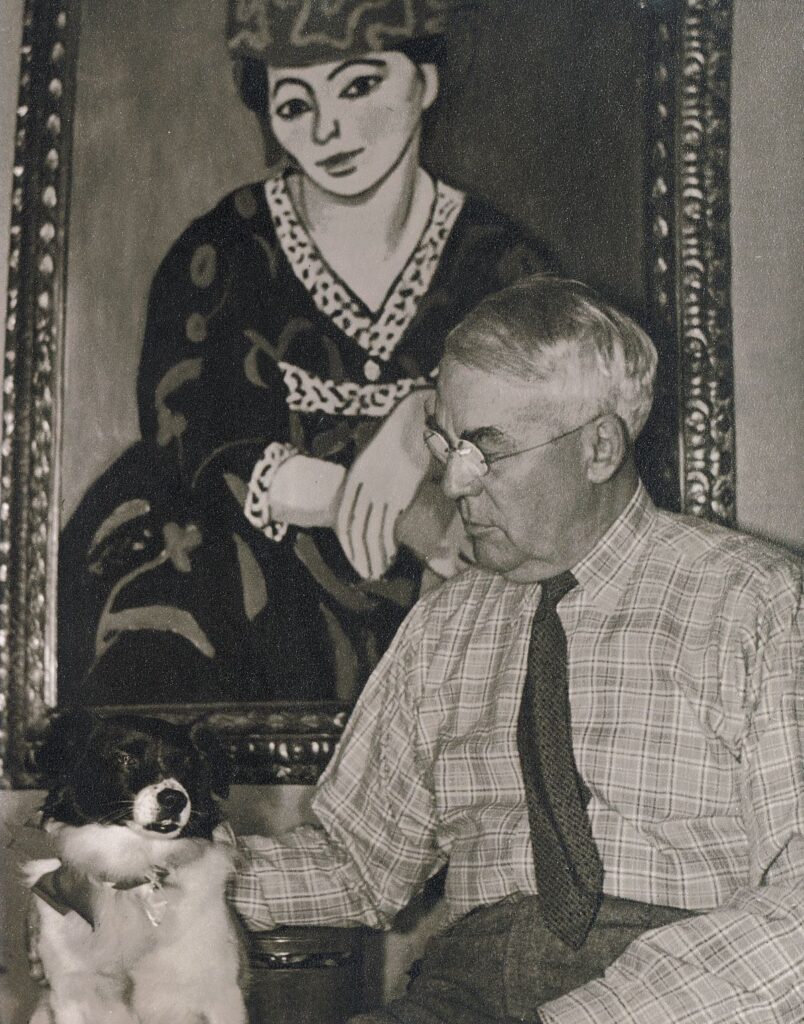

By the time I first went to Merion in the 1970s, the vigorous spirit of Albert Barnes—that pugnacious can-do-kid who rose from poverty to pharmaceutical riches with the development of the antiseptic Argyrol and then went on to amass the finest collection of early modernist art in the world before almost anyone else had an eye for it—had faded. He’d been dead for almost two decades; Violette de Mazia, designated keeper of the flame, was very much in charge, but the atmosphere was uninviting and almost cult-like in its rigid rules for entrance and the reverential hush hanging over it all. When the “new” Barnes first opened in 2012 in Philadelphia, I noticed a similar spirit of fussy authoritarian rigor, but by 2018 things had changed, giving us the foundation we have now—relaxed and inviting with innovative programming and vigorous community outreach while also maintaining the galleries just as they were in Merion.

Would Albert Barnes approve? Let’s imagine him around today, and, improbably, let’s imagine him somewhat mellower. He’d surely not have welcomed the high-toned gift shop or the sleek restaurant, and definitely not the Annenberg Court, named after the family of his arch nemesis Walter Annenberg, but I think he would have come to see that in becoming less Eurocentric, less masculine in its programming, the foundation’s current goals are not inconsistent with his. I think he also might well have liked many of the less obvious changes, such as the fact that visitors are now encouraged to snap photographs and share them with the foundation.

But what of his mission on behalf of the emancipating power of art? There is no Argyrol for the injuries inflicted by racial prejudice, but there is art, and this is where The Barnes Then and Now is especially convincing in its careful descriptions of just how the Barnes Method of unmediated encounters with art, with learning to see without the interference of wall labels and so forth, can continue to emancipate and liberate. Barnes had first employed his method by introducing the mostly Black workers in his West Philadelphia factory to the masterpieces he installed there; the book is especially careful in covering both the successes and the contradictions of these early encounters. Barnes created the foundation to continue this work in Merion, but it wasn’t until it moved to Philadelphia that it could go from a somewhat rarified experiment to a much more comprehensive mission, joining the city’s superb Mural Arts program and other organizations to engage significant numbers of people of various ages, races, and backgrounds.

One of the more disturbing issues in The Art of the Steal concerns Lincoln, the historically Black university fifty miles from Philadelphia; it is here that The Barnes Then and Now addresses the controversy surrounding the foundation’s move, while also showing how the Barnes can evolve in a way consistent with its founder’s wishes. In 1946, after meeting Dr. Horace Mann Bond, Lincoln’s first Black president (and father to Julian Bond who speaks at length in the documentary), Albert Barnes was eager to unite the two educational institutions, eventually giving Lincoln significant control of the Barnes by giving it control of the foundation’s small board of trustees. I will abbreviate the controversy: in 2003 various forces conspired to expand the board so that the Lincoln trustees were greatly outnumbered, clearing the way for the move to Philadelphia. Lincoln and its students were for the most part out in the cold—an ugly story.

What you will find in The Barnes Then and Now is a lengthy conversation between Brenda A. Allen, current president of Lincoln, and Thom Collins, director and president of the Barnes, repairing the connection between the two institutions. What they envision is a collaboration that will be a model to encourage African American students and faculty across the country to play a significant part in museums, admitting as they do so that they are only at the beginning of this projected road to redemption.

For anyone liable to think the Barnes’s mission impossibly utopian, or for anyone inclined to move through the superb new building by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien consuming the art and ignoring that mission, The Barnes Then and Now is an indispensable corrective and an inspiring guide.