Whether it’s Hieronymus Bosch, the details of whose life are lost to time, or Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose reclusive later years add to the mystery of his reputedly eccentric personality, there are any number of artists whose biographies are less than full, whose comings and goings are uncertain, whose intercourse with the world was so defiantly on their own terms that they have left little trace of their thoughts, their intentions, or their ambitions. When it comes to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American artists, Guy Carleton Wiggins occupies a unique place in the annals of obscurity. Not that his work is or was unknown. Far from it. He exhibited widely, earned any number of awards, and his canvases entered the collections of major museums across the country, including those of the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery of Art. But as Wichita Art Museum curator Mary Frances Ivey learned while organizing the current exhibition Country, City, Shore: America and Abroad in the Paintings of Guy C. Wiggins and Company, the paper trail for this American impressionist is slight, despite a life lived actively amid the mainstream of American art.

Guy Wiggins was the son of J. Carleton Wiggins (1848–1932), a Brooklyn-bred, Barbizon-inspired artist whose bucolic vistas—often populated by sheep and cows—brought him considerable success. Wiggins père studied for a time with George Inness and began showing at the National Academy of Design in 1866. Around 1880 he traveled to Paris and for the next fourteen years moved about Europe with sojourns stateside, where Guy Carlton Wiggins was born, in Brooklyn, in 1883. The following year, the family returned to Europe, living primarily in England. Before the age of ten, young Guy was reportedly making admirable forays into watercolor.

By the turn of the century, seventeen-year-old Wiggins was back in the US, studying architecture at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and then drawing at the National Academy of Design. He also studied with William Merritt Chase at the New York School of Art, and possibly with Robert Henri as well.In 1912 he became one of the youngest artists to have a work purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Entitled Metropolitan Tower, the oil depicts the seven-hundred-foot skyscraper (patterned after the campanile in St. Mark’s Square, Venice) erected at Madison Avenue and 23rd Street by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in 1909. With the tower partially obscured by smoke rising from neighboring buildings and set against a sunless sky, the painting manifests the hazy, atmospheric effects that would become a hallmark of Wiggins’s work as an American impressionist.

Accustomed to life in Europe, Wiggins returned for a six-month stay in 1914, during which he married Dorothy Stuart Johnson, the daughter of one of his father’s patrons. Home again, he established a residence in Olde Lyme, Connecticut, while maintaining a presence in the city. Elected an associate member of the National Academy, he was soon to see the first of the many awards that would come his way: the Hartford Prize from the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts. Throughout the teens and twenties, the honors kept coming and Wiggins found ready takers for his work, but by the 1930s buyers became rare. Faced with this new reality, Wiggins spent more time in Connecticut, where he opened the Guy Wiggins Art School.

While this bio isn’t exactly scanty, it is slender. Ivey, Sarachek Curatorial Fellow for Wiggins Studies at the Wichita Art Museum, discovered while developing Country, City, Shore that there seems to be very little documentation available on the artist’s working methods or pedagogical approach, no personal take on his peers, and even little in the way of exhibition reviews. Ivey’s efforts to pull together “a posthumous CV” have included accessing depositories at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Archives of American Art, and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and she suspects this dearth of information stems, in part, from the fact that Wiggins went into eclipse with the advent of World War II. “I can only speculate,” Ivey says. “This is because he did not seem to engage with that historical moment as other artists tried to do in their work. Charles Burchfield, for example, although he is sometimes described as an American impressionist, was really more of a modernist and much more interested in the contemporary dialogues about what paint can be doing. If Wiggins had any regrets that he did not do that, I don’t know, but I think that is the point at which he was left behind.

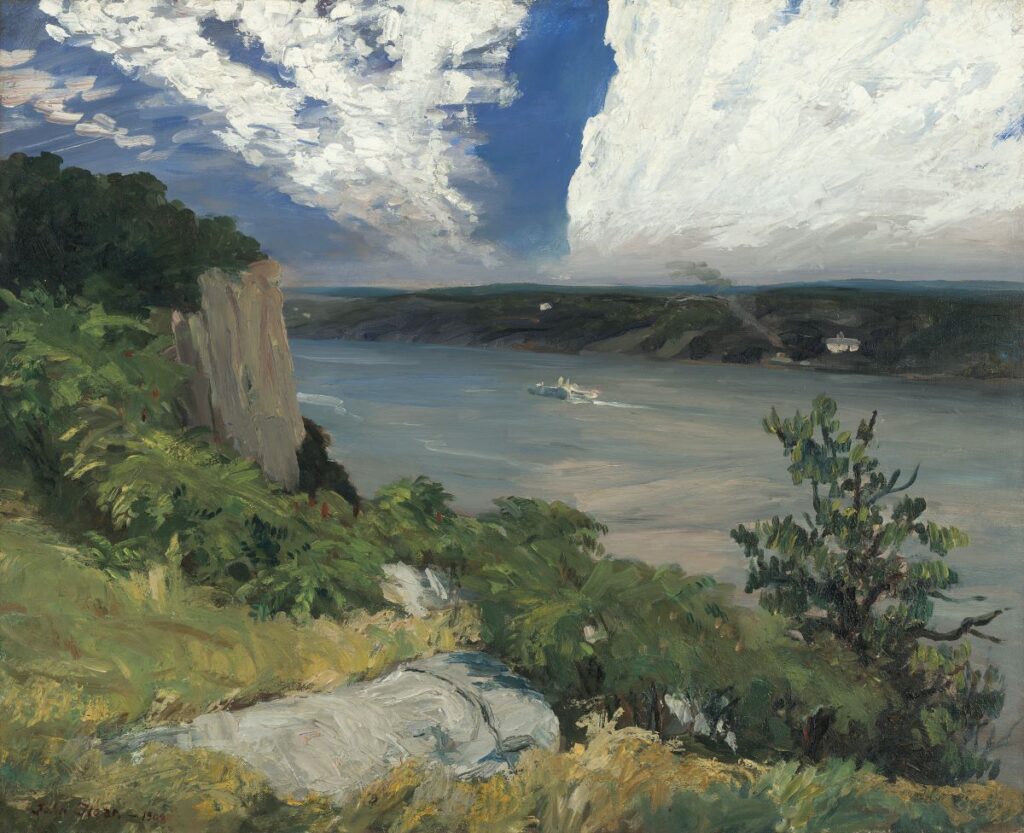

While Country, City, Shore is centered largely on Wiggins pieces donated to the museum by local collectors—most notably, Alvin and RosaLee Sarachek—Ivey had to take a contextual approach in offering an exploration of the artist’s work. “To study Guy Wiggins is to study an art historical moment. It’s almost impossible to meaningfully understand his body of work without thinking of his contemporaries,” she relates. “I most look forward to visitors spending time with Wiggins’s Across the Gloucester Shore (Fig. 1), Childe Hassam’s Jelly Fish (Fig. 6), and John Sloan’s Hudson Sky (Fig. 5). The range of maritime subjects in these three closely contemporary paintings and the artists’ individual brushwork underscore that the American impressionist movement was, more precisely, a moment of American impressionisms. Hassam, who is credited with introducing this French painterly mode to US artists, dots his cobalt-blue waters with white daubs for jellyfish bells and sculpts the weather-beaten rocks from bold hatch marks in navy blue, mustard yellow, and peachy pink. Sloan, who was a founder of the Ashcan school and taught at the Guy Wiggins Art School, mirrors an expansive sky in the river’s reflection, punctuating his painting with thickets, a puttering boat, and waterfront homes using heavily impastoed sweeps and drags of his brush. Wiggins crops his subject closely to focus on built environments at the water’s edge. Skiffs, canoes, and fishing boats dock in the foreground, where he attends to each surface with glistening highlights, ripples in the lapping water, and loose dashes for details obscured by shadows.”

Views of New York City were a favorite subject for Wiggins, especially with snow falling, as in Fifth Avenue Storm (Fig. 4), and Looking Down 5th Avenue (c. 1947), which Ivey brings together with Ernest Lawson’s St. John the Divine, New York City, in Winter (Fig. 7). “Wiggins and Lawson admired one another’s art and traded paintings, and Lawson also instructed students at the Guy Wiggins Art School,” Ivey says. “Both artists maximize the affinity of impressionist paint-handling for representing atmospheric qualities, and both picture New York City veiled with snow, mist, and skyscraper shadows. Yet, Lawson explores atmospheric effects mediating city vistas—like the setting sun’s glow, haze, and golden cast—with soft tonal transitions and blurred brushwork, whereas Wiggins’s cityscapes tend to focus on heavily peopled streets, bustling river ports, and flags flapping from awnings, all rendered with energetic strokes, dashes, and sharp color contrasts.”

Wiggins died in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1962, while vacationing. His obituary in the New York Times of April 26, 1962, identified him as “primarily a landscape artist, painting in a vigorous style deriving from Impressionism.” Accompanied by a photo of the man looking rather haughty and wearing a bow tie, it noted the various awards he had received and his membership in several clubs, including the National Arts Club and the Salmagundi Club. The eye-pleasing aesthetic he practiced until the end had long ago been superseded in the cultural consciousness by tougher approaches to representation as well as abstraction. So, in some sense, he had labored in the shadows for years, but as this exhibition demonstrates, he did have his day in the sun.

Country, City, Shore: America and Abroad in the Paintings of Guy C. Wiggins and Company is on view at the Wichita Art Museum through April 7, 2024.

THOMAS CONNORS is an arts and culture writer based in Chicago.