Artist of Iron Samuel Yellin and the Landmark Year 1922

Fig. 1. Door by Samuel Yellin (1884–1940) for his personal office in the Samuel Yellin Metalworkers Building, Philadelphia, 1922. Impressed “Samuel Yellin 1922” at the lower right. Iron with red felt; height 74 1⁄4, width 34 1⁄2, depth 5 7/8 inches. Courtesy of the Leeds Art Foundation; except as noted, photographs are by John Carlano.

The year 1922 has always seemed magical to me. Gertrude Stein published Geography and Plays; James Joyce issued Ulysses; and T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land appeared. On the European continent, modernist works tested the boundaries of painting. Giorgio de Chirico painted Il figliol prodigo, Paul Klee created Twittering Machine, John Miró completed The Farm, and Pablo Picasso unveiled Two Women Running on the Beach. In America, Maxfield Parrish looked backward to romanticism in Daybreak, while Charles Sheeler rushed toward the angularity of cubism in Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting. Maurice Ravel’s orchestral arrangement of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition premiered in Paris, while nearby Antigone by Jean Cocteau appeared on the stage of the Théâtre de l’Atelier in a production designed by Picasso, with music by Arthur Honegger and costumes by Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel. Louis Armstrong left New Orleans for Chicago to join King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Paul Hindemith debuted his fourth string quartet (op. 22), Dimitri Shostakovich completed his Three Fantastic Dances, op. 5 and Suite in F-Sharp Minor, op. 6, both for piano, and Alexander von Zemlinsky premiered the opera Der Zwerg (libretto adapted from a short story by Oscar Wilde). Bauhaus painter, sculptor, and teacher Oskar Schlemmer captivated the world of dance with the “artistic metaphysical mathematics” of his Triadic Ballet, with a score also by Hindemith; Fritz Lang made Dr. Mabuse der Spieler; and Robert J. Flaherty debuted Nanook of the North. And in these heady times The Magazine ANTIQUES was born.

Fig. 2. Yellin in his personal office in the Samuel Yellin Metalworkers Building in a photograph of c. 1922. He is seated at the massive refectory table where he met with architects, clients, employees, and students. Weitzman School of Design, University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives, Samuel Yellin Collection.

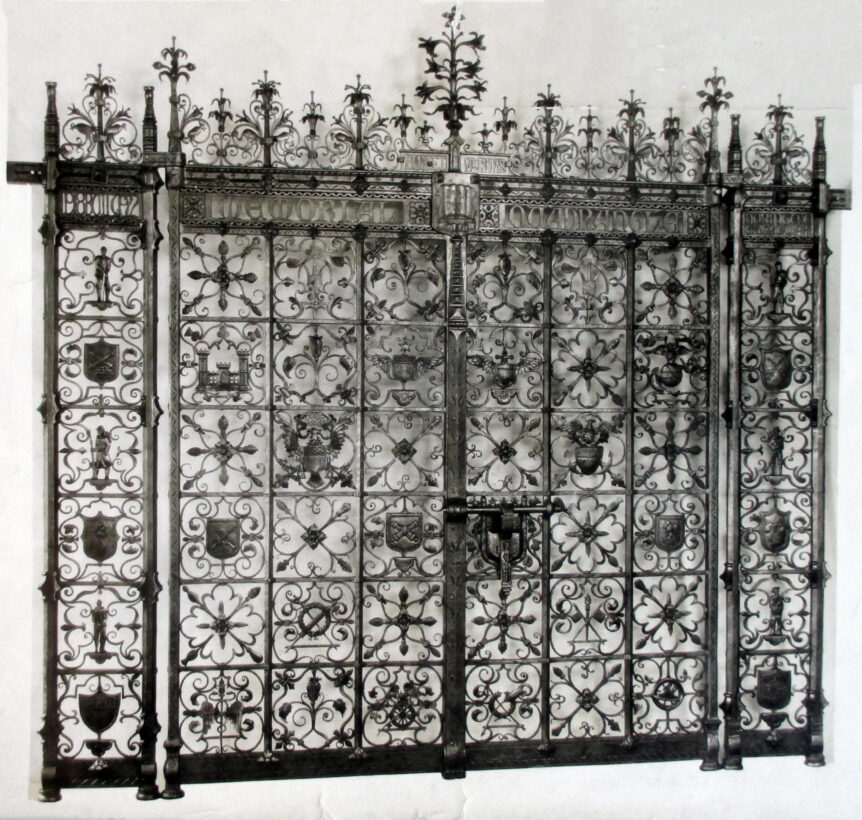

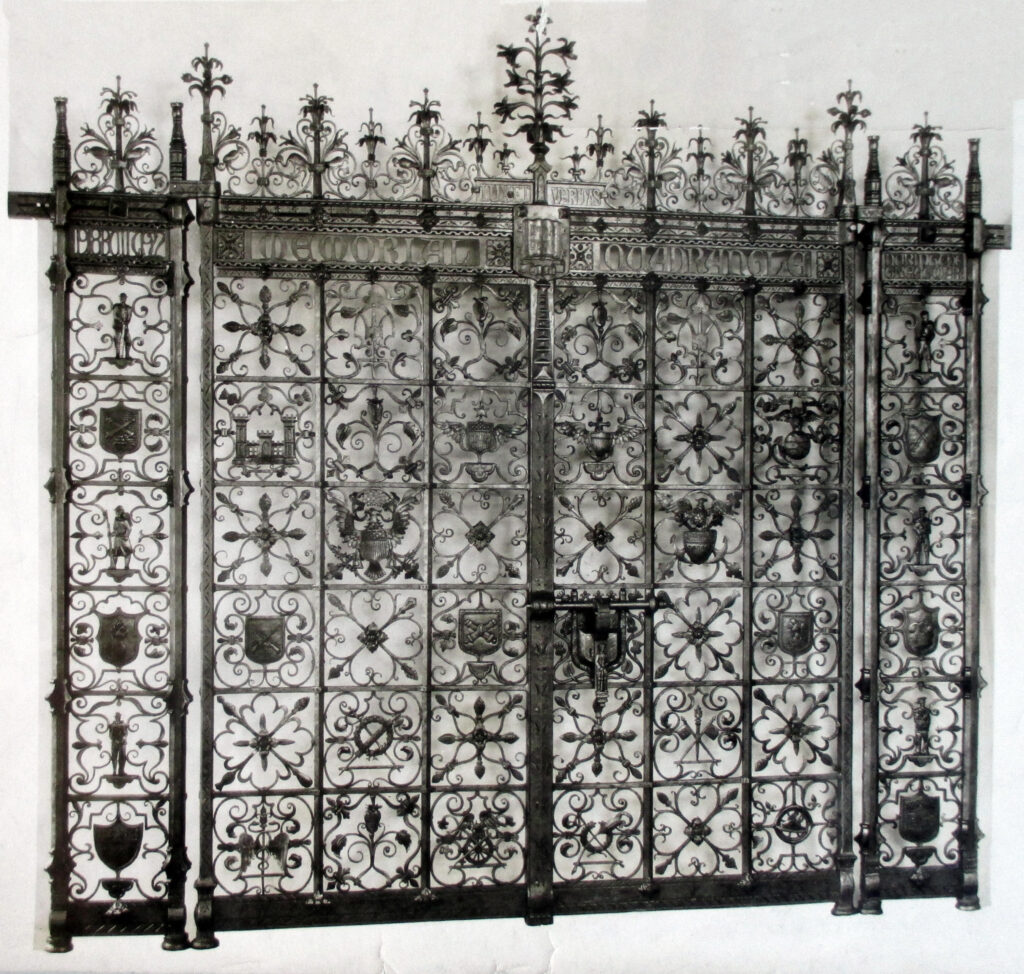

It is easy to miss, but hard to overstate the singular importance of design periodicals in the early twentieth century. As American design truly came into its own in the first years of the new century, ANTIQUES was uniquely poised to join the well-established American and European design press, presenting a remarkable new voice contributing to the public’s understanding of historic design. Ironworker Samuel Yellin enjoyed support from design critics and exposure to readers across the country through important articles virtually from the time he first arrived in Philadelphia from Ukraine about 1905 through his death in 1940, when the New York Times celebrated his achievements in a lengthy obituary. 1922 was similar to other years for Yellin, with numerous articles appearing in key periodicals, many of which celebrated his outstanding ironwork for the Memorial Quadrangle at Yale University (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3. Charles William Harkness Memorial Gates for Harkness Memorial Tower, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 1921–1922, in a photograph of c. 1922. University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives, Samuel Yellin Collection.

Fig. 4. Harkness Memorial Tower, Yale University, designed by James Gamble Rogers (1867–1947), with Yellin’s gates at center, in a photograph of c. 1922. University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives, Samuel Yellin Collection.

We can use this coverage to calibrate his art and the state of design criticism at the time. Critic Dorothy Grafly called Yellin’s “imposing and imaginative” gates for Yale “portals,” and a “tribute to [a] Hero,” namely Edward Harkness’s “patriot son, a student at Yale who fell in the world war.”1 At this point in the design critics’ and their readers’ development of understanding of Yellin’s work, it is notable that Grafly reached a fascinating insight regarding the methods of “adaptation” and stylization essential to the ironworker’s method. She quoted Yellin, who explained that he had suggested the military insignia in the gates at Yale “without carrying it out literally in the iron.”

Grafly’s 1922 analysis of Yellin’s achievements revealed that rather than seeking a faithful reproduction of such details, Yellin stated that there were times when he could not work directly from designs but instead needed to “go down to the forge room” to “play with the iron.” The “different and more satisfactory result” he sought was a reflection of the medium of wrought iron, where “designs serve merely as a guide.” Grafly marveled at Yellin’s ability to combine the “Gothic with the modern through a skillful modulation of conventionalized design.” She argued that it required the “courage and genius of an artist” to unite the twentieth century with Gothic style, creating both “dignity and beauty” in the design.

Fig. 5. Detail of the door for Yellin’s office, showing cross-overlaid decorated straps of iron and one of thirty large decorative bosses hiding the joinery across the surface of the door.

Fig. 6. Detail of the door for Yellin’s office, showing the dog-shaped lever handle, which is both visually entertaining and fits perfectly into the hand of the user.

Iron, unlike clay, Grafly argued, “can never fully attain realism” and was necessarily archaic in its presentation, requiring conventionalized systems of ornament, but not a “quaint, flat presentation of symbols.” A sense of humor was also essential in this work for the author, who stated that Yellin presents his “doughboys with service stripes, because, as he laughingly assured, ‘they were under fire in the forge room.’” Avoiding the monotony possible in his art form, this master craftsman created novel, intricate designs that are “paradoxically both restful and stimulating.” For Grafly, the genius of Yellin’s work lay in the “poise and dignity of the general impression,” contrasting the excitement of “endless variation of its detail.” She noted the fruitful, verdant peace in a “tree of life” on one side of the lock, and the torn branches of a tree damaged by war or drought on the other side. Despite the fancy of her interpretations, she insisted that the artist’s imagination was “necessarily bounded by stern practicability.”

Fig. 7. Detail of the door for Yellin’s office, showing three repoussé panels. The flanking panels illustrate techniques such as repoussage, incising, drawing, upsetting, and puncturing, with the center panel a tableau of commerce, where a client or his representative delivers payment (a bag of coins) to the head of shop.

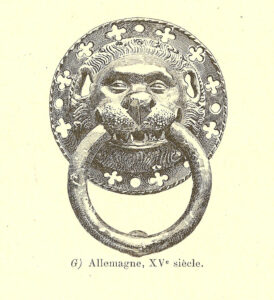

Fig. 8. Fifteenth-century German door knocker pictured in L’Art pour tous, new series, vol. 44, no. 2 (1905), Pl. 1, fig. G. Yellin owned a copy of this volume and kept it in the firm’s library.

As elements of the design world raced forward, embracing modernist designs of the early 1920s that stemmed from the arts and crafts movement, American iterations of art deco, and machine-made product innovations, Yellin harkened back to a time of handmade artisan products rooted in medieval and Gothic styles. The same tensions between the new and the antique played out in the design press, where some commentators raved about the pared-down aesthetics of modernism while others called it a fad that could never measure up to the glory days of historic modes. The old-world charm and artisanal skill that Grafly found in Yellin’s shop were brilliantly exemplified in his 1922 masterpiece of design: a door in his personal office at his workshop (Fig. 1). Rarely have old and new been brought together more seamlessly than in this boldly simple design, ornamented with complex and virtuosic repoussage, incising, and finishing. Though Yellin used his office—where he met with architects, clients, and art and design critics—as a kind of constantly evolving laboratory for his best design concepts, because the door was fixed in a specific prime location in the space, it held a place of honor (Fig. 2). During planning sessions and meetings, he could easily point to a range of historic works from medieval to Gothic based on Spanish, French, German, and Italian precedents, meant for public, ecclesiastical, banking and business, and domestic installations. He always kept a survey of his finest works so he could specifically negotiate designs, but the door was especially important because it was an object made of iron demonstrating techniques from forging to repoussage, hammering to incising and complex joinery that framed panels into a whole with large straps of forge-welded sheet iron (Fig. 7).

Fig. 9. Detail of the door for Yellin’s office, showing the ape-like lion door knocker, similar to the one in Fig. 8, raised in dramatic repoussage and surrounded by twelve quatrefoils. At left, workers hammer an iron bar on the anvil; at right, blacksmiths join scrolled strap hardware to a door.

Set with seven strata, each with three cells, the composition depicted various aspects of ironmaking, from forging and welding to joinery and construction, all presented in idealized neoclassical scenes. Each tableau portrayed a specific activity with metalsmiths in various types of historic costume, but they were all unified in the typical medieval portrayal of the happy toiler. Wizard-jester-ironsmiths worthy of Maxfield Parrish jauntily flank the merry workers striking against the anvil at top center. Some panels represent fastidious chiseling to the surface of sheet metal or repoussé hammering to the opposite side, while others survey techniques of scrolling, puncturing, and even complex sculpting of foliage. Joinery and surface finishing and various aspects of quality control are all depicted as well. In one of the most central panels, Yellin reminds us that his was a business, as nobles exchange a bag of currency for commissioned work completed by a workman set back within the drafting room (Fig. 7, center).

The overall grid pattern for the door was created with thick strips of iron woven across the surface and incised with many novel geometric patterns. Each juncture of horizontal and vertical strapwork was punctuated with a large elaborate boss—thirty in total—each unique (Fig. 5). The door closure was formed from a cylindrical lever in a decorated collar, with a handle in the form of a dog’s head, whose long tongue descended below its mouth and curled upward in a smile (Fig. 6). The ring handle and knocker were suspended from the stylized face of a lion (Fig. 9). This marvelous ornament was strongly influenced by fifteenth-century German precedents, likely known directly to Yellin, but definitively present in his personal library of art, design, and architecture books (Fig. 8).2 The reverse side of the door revealed the brilliant repoussage technique that created the images on the front (Fig. 10). In its design and execution, the door was extraordinary as a conveyer of the history and techniques of ironmaking. As we draw closed the door on a year of centennial celebrations of the founding of The Magazine ANTIQUES, this door, made by Yellin for his personal office at his forge building at 5520 Arch Street in Philadelphia, reminds us of the impulses that propel design forward and the moorings that anchor us all to our shared history in material culture.

Fig. 10. Detail of the verso of the door for Yellin’s office. The ring mimics closely the one on the front but it is held here by a decorated collar incised “Y” for Yellin.

1 All quotes from and references to this article in this and subsequent paragraphs are from Dorothy Grafly, “Yellin’s Art Seen in Memorial Gates,” unidentified publication (likely the Public Ledger, Philadelphia), dated 1922 in pen, Samuel Yellin Scrapbook, University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives, Philadelphia.

2 The illustration referenced is a fifteenth-century German design illustrated in L’Art pour tous (Fig. 8). See also Wilhelm Schmitz, Die Mittelalterlichen Türen Deutschlands (Trier: Schaar and Dathe, 1905), cover. Both volumes were in the Samuel Yellin firm’s library.