On September 1, 1878, impressionist painter Claude Monet declared, “I have pitched my tent on the banks of the Seine at Vétheuil [France], a ravishing place from which I should be able to extract some things that are not bad.”1 Time has proved that an understatement: during the period he spent in the small village on the Seine River, through the end of 1881, Monet produced about two hundred paintings, some of which helped to establish the direction of his later work.2 In 1968, almost a century after the departure of Monet, abstract expressionist and expatriate American artist Joan Mitchell relocated from Paris to Vétheuil, where she remained until her death in 1992. The fact that she lived in a house that literally overlooked the place Monet had occupied earlier invited comparisons between the artists that eventually exasperated Mitchell; her attitude toward her predecessor in Vétheuil went from “adoration” in the 1970s, to ambivalence and a need to move out from under his shadow in the 1980s, to “an outright disavowal of any influence from the French painter by the end of her career.”3 Despite her protestations to the contrary, Mitchell’s work at Vétheuil undeniably spoke to that of the iconic Monet.

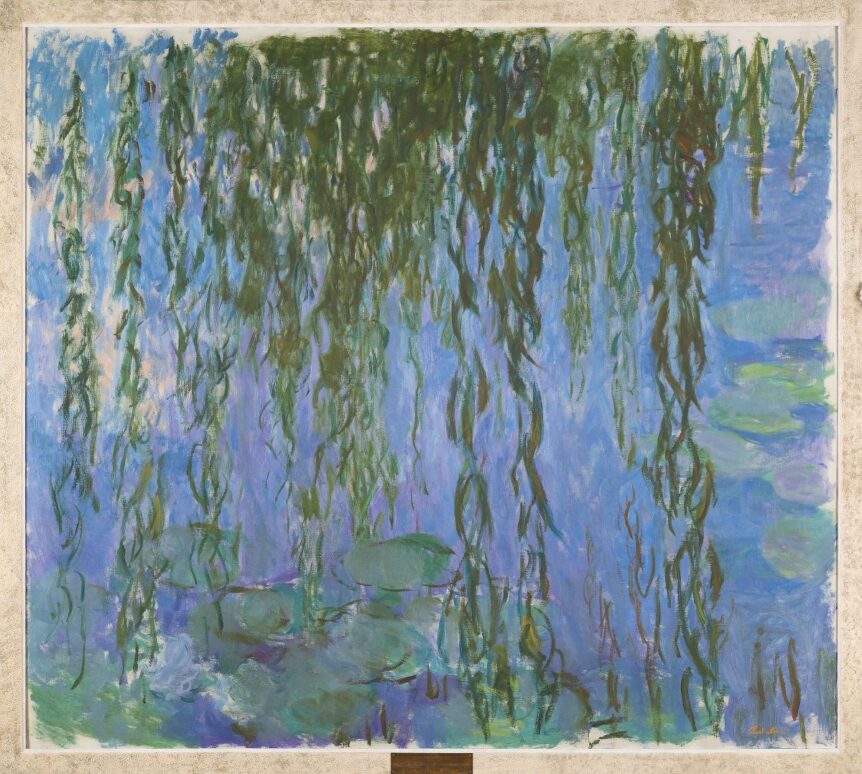

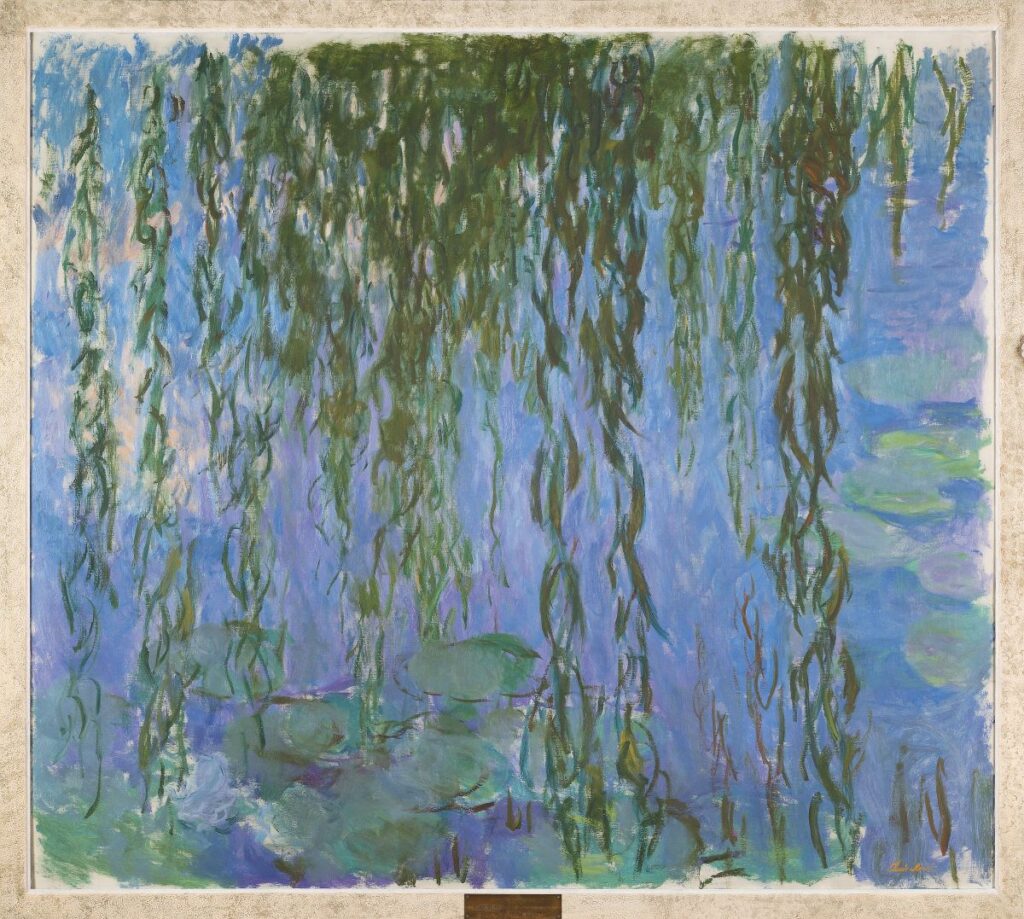

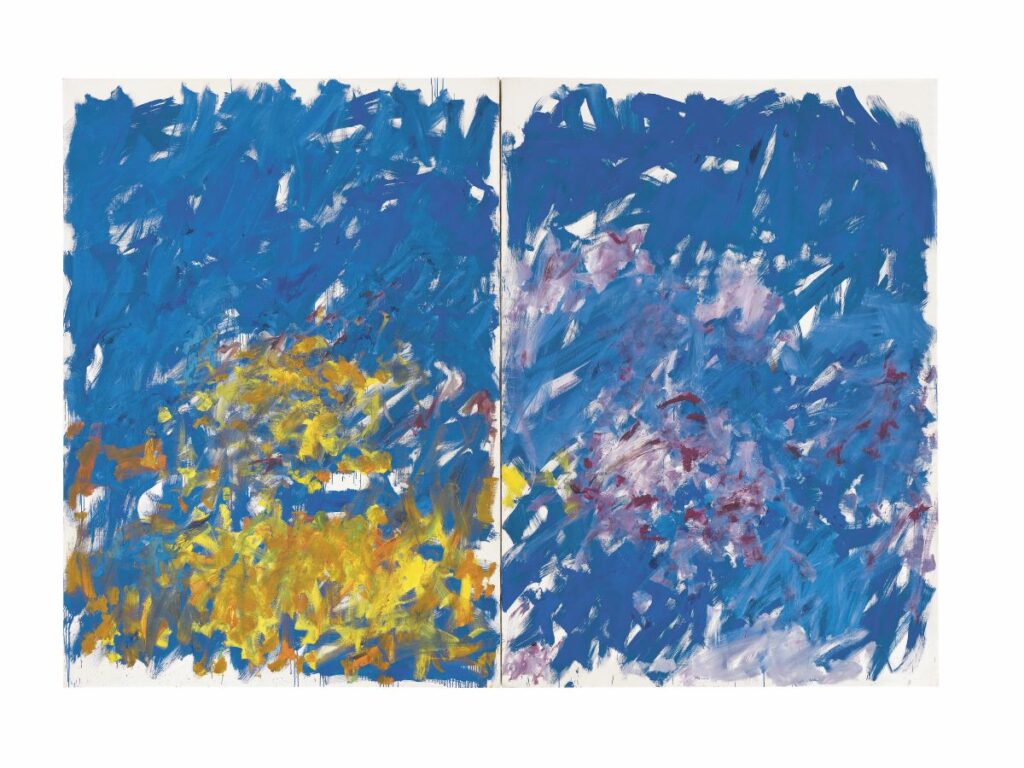

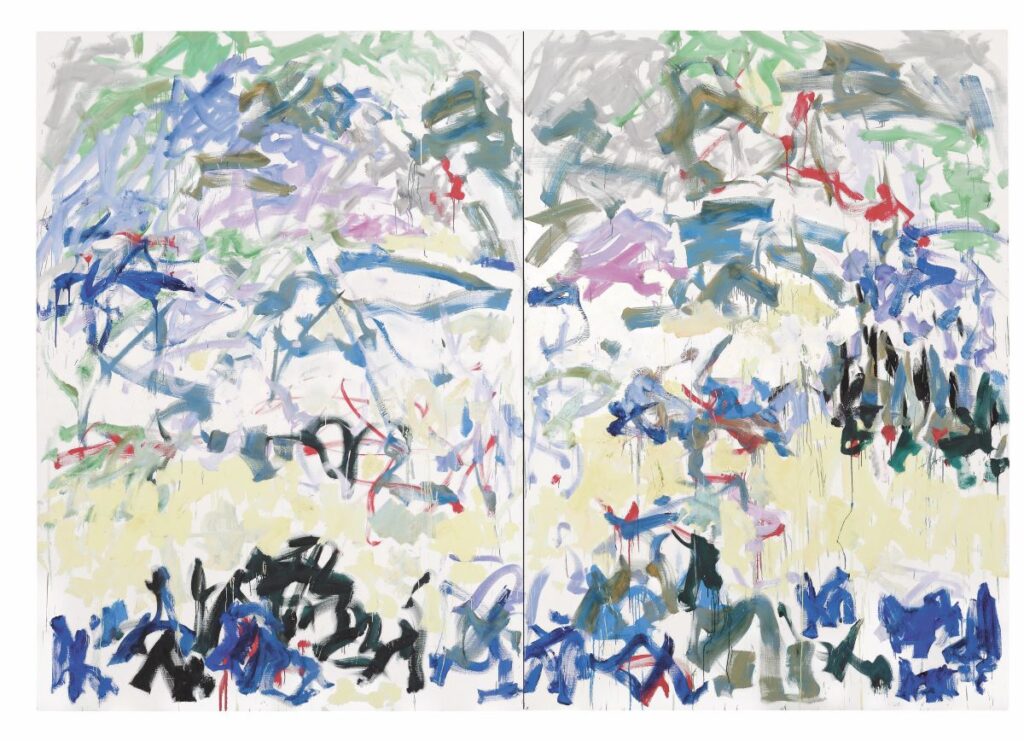

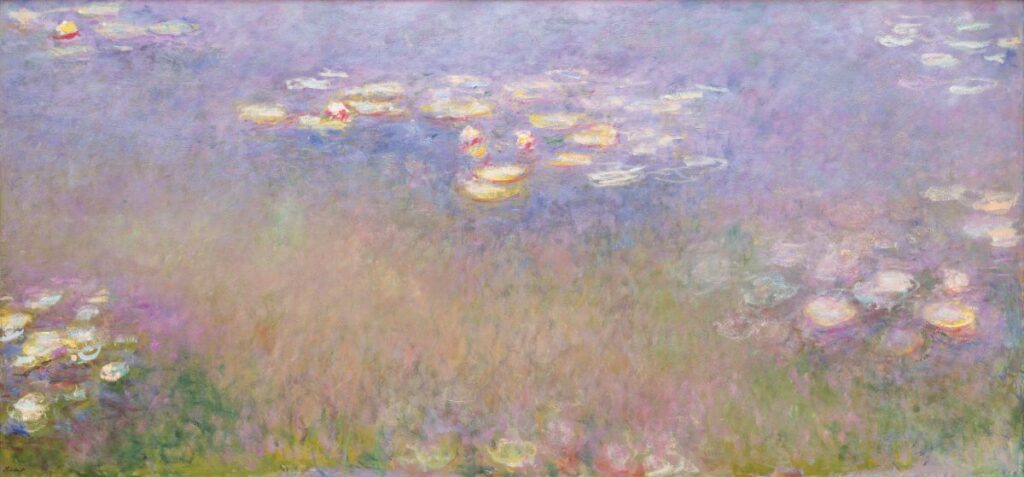

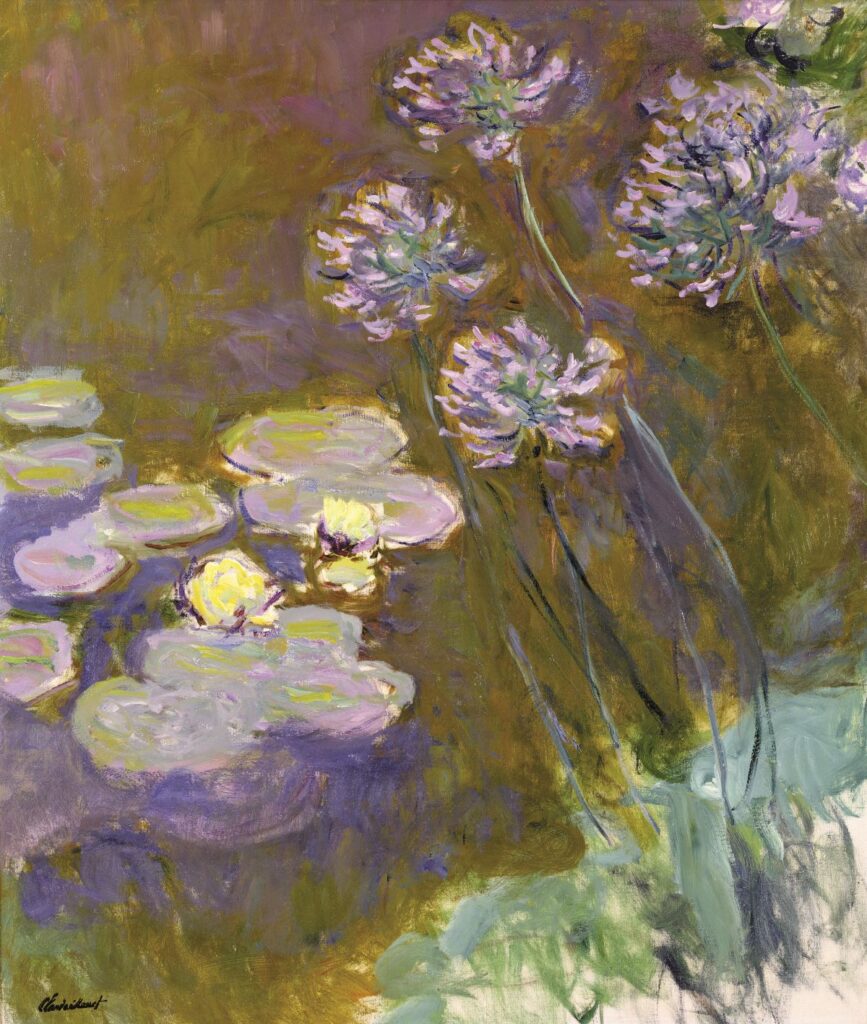

This point was made visually through the stunning and convincing juxtapositions of works by the two artists in an exhibition mounted at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, Monet-Mitchell, between May last year and this February, and substantiated in its catalogue.4 A new version of that exhibition, Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape, now at the Saint Louis Art Museum, offers a somewhat different group of artworks as well as a different perspective on the shared interests of the two artists in landscape painting. (Notably, the Saint Louis presentation lacks the retrospective of the work of Mitchell that complemented the Paris show, the first significant exhibition of her work in Europe in more than thirty years.5) Nonetheless, Simon Kelly, curator of the Saint Louis exhibition, underscores its significance in “foregrounding the work of a major woman artist.”6 The Saint Louis Art Museum, which lent to the Paris show, is featuring a dozen works by each artist, including eight by Mitchell not seen in the previous exhibition. The paintings by Monet are largely from the Musée Marmottan Monet and the Mitchell works from the Fondation Louis Vuitton, although two highlights are Water Lilies (Fig. 5) by Monet and Ici (Fig. 8) by Mitchell, both from the Missouri museum’s own collection.

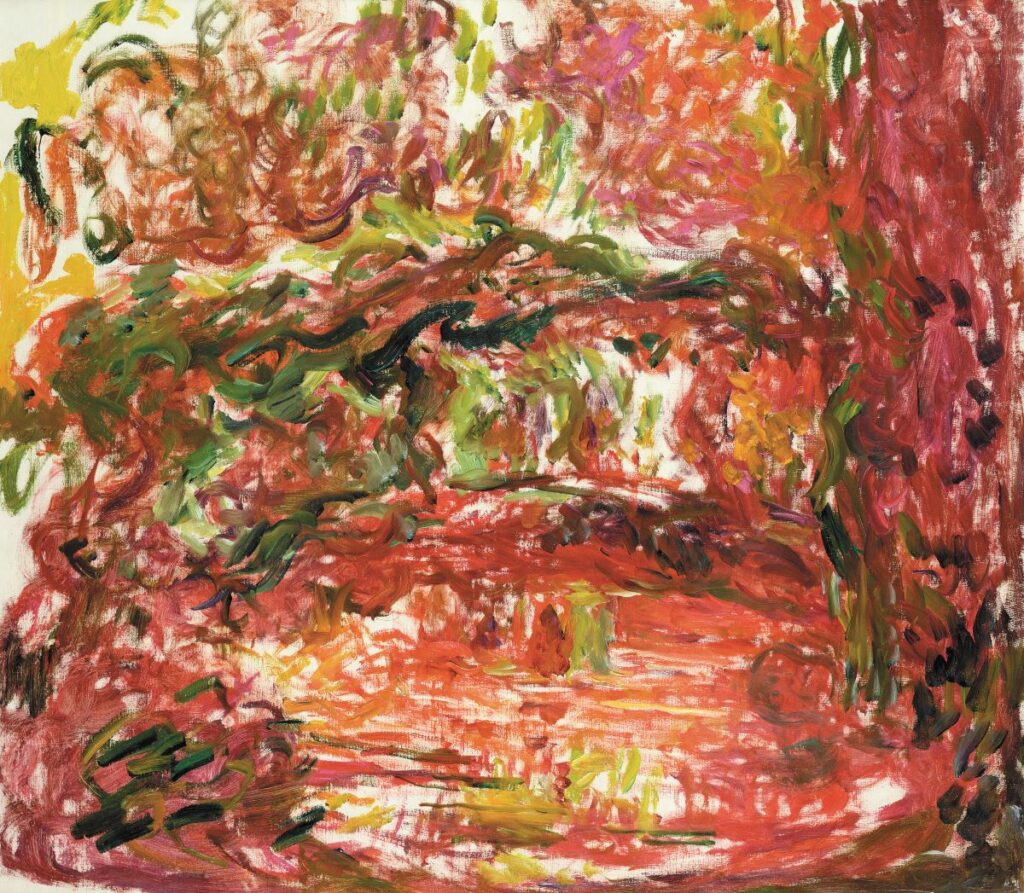

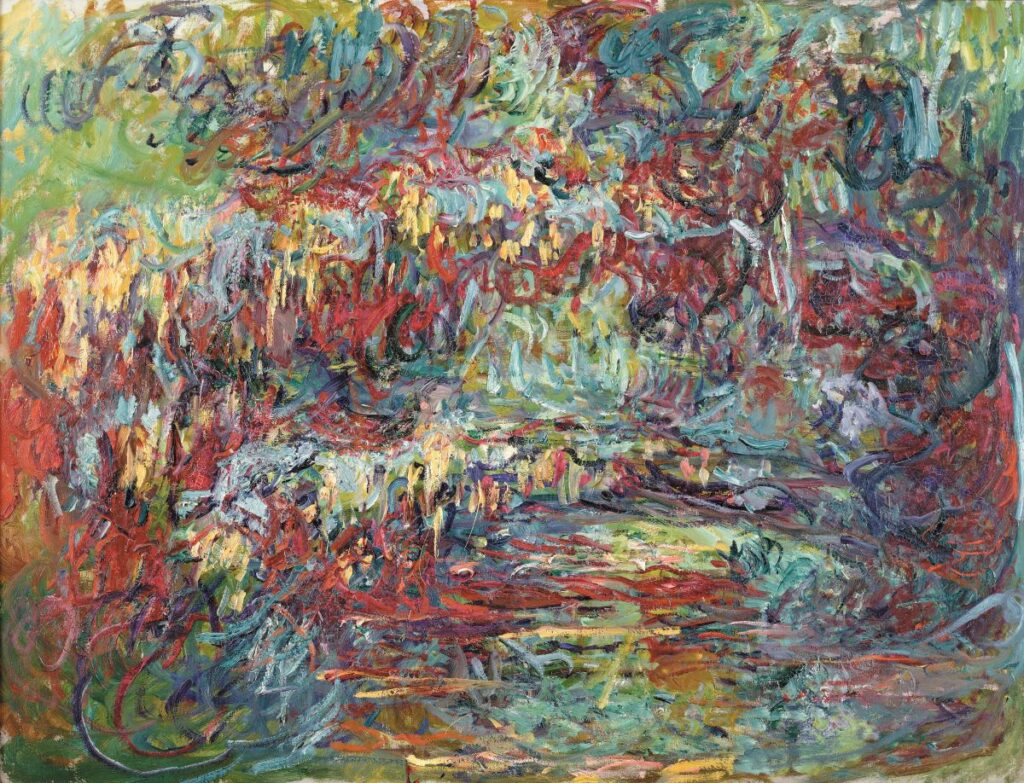

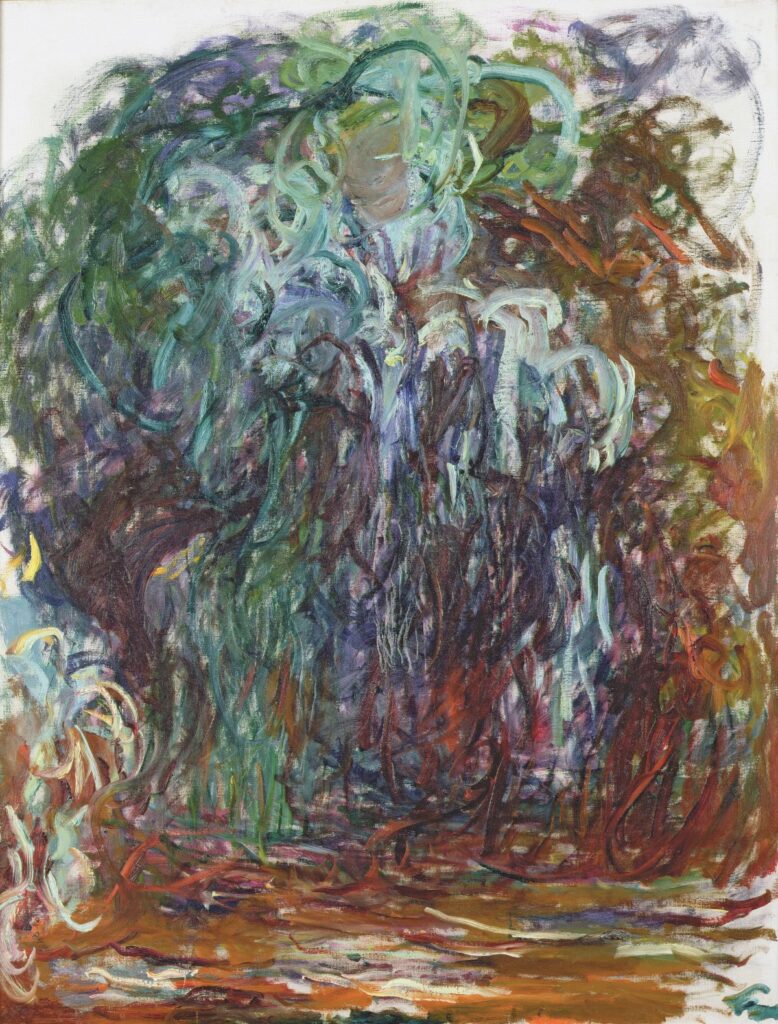

Exhibiting the work of Mitchell alongside that of Monet might be seen as a strategy to boost visitation, given the perennial appeal of French impressionism and especially of its best-known proponent. Ever since the “Monet revival” in the 1950s, the artist has enjoyed a nearly uninterrupted series of exhibitions in Europe, North America, Asia, and beyond. Indeed, at the time of the exhibition The Unknown Monet, in 2007, organized by the Royal Academy and the Clark Art Institute, art historian Patricia Mainardi observed that “I find it hard to believe that at this date there is anything left unknown about Monet,” given the spate of exhibitions of his work, including Monet at Vétheuil: The Turning Point (1998), the show that most deeply explored the brief but productive period the artist spent in the village.7 However, the Paris and Saint Louis exhibitions fully justify revisiting Monet’s Vétheuil period, and the pairing of the two artists shows undeniable affinities between their paintings. The fact that Monet and Mitchell each spent a part of their career painting in Vétheuil, chose similar subjects, and executed works at a large scale, makes it possible, as Kelly states, to see the parallels between their uses of color and “highly gestural brushwork,” as well as the place of abstraction in each oeuvre. When Mitchell in 1957 remarked that she liked “late Monet but not early,” she was already expressing a preference for the freer, more abstract work of the artist with which her own canvases have been compared (Figs. 11, 13, 14). 8

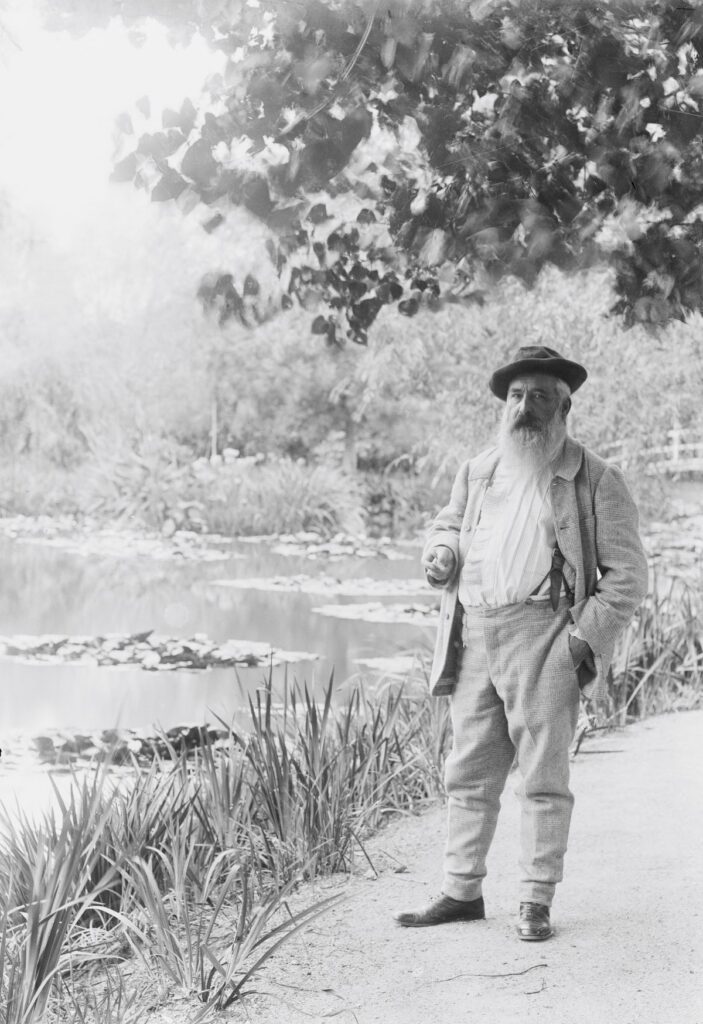

It must be noted that the late work of Monet that appealed to Mitchell was not painted in Vétheuil but rather in Giverny, about ten miles downstream, where the artist moved in 1883, purchased a property in 1890, and remained there for the rest of his long life, which ended in 1926. Nonetheless, art historian Susan Grace Galassi argues that the paintings Monet executed in Vétheuil, especially those of the ice floes that dramatically descended the Seine when a historic cold spell ended in the winter of 1880, provided a model for the composition of some of the artist’s water lily paintings made in his famed garden at Giverny a decade or so later. The freezing weather over the two winters he was there was just one of a number of challenges Monet faced in Vétheuil: he experienced acute and chronic financial woes, and witnessed there the illness and death of his first wife, Camille. Claude and Camille shared living quarters in Vétheuil with his promoter Ernest Hoschedé, Hoschedé’s wife, Alice (whom Monet would later marry), and the children of both couples.9 The lack of funds and large household meant that Monet had nothing like the spacious house and studio, with its luxurious gardens, he was later able to build in Giverny.

In fact, Monet’s retreat to Vétheuil had little in common with his later move to Giverny other than geography. In the first instance, leaving Paris was largely motivated by economic considerations at a time when Monet was struggling to meet his family’s needs. By the time he settled in Giverny, by way of contrast, he had the means to develop the extensive gardens that became the focus of his artmaking in the last phase of his career. The international fame that Monet enjoyed by the turn of the century drew to the Norman town scores of followers, including Mitchell’s own teacher-to-be at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the mid-1940s, impressionist painter Louis Ritman, who “worked in the orbit of Monet at Giverny in the 1910s and 1920s, producing sun-dappled imagery of the Giverny landscape,” as Kelly recounts.10 Ritman began teaching at the Art Institute in 1930 and continued to do so for thirty years. While his biographers have noted that “practically no attention has been paid to this important and successful period in the artist’s career,”11 his time in Giverny inspired Mitchell to travel there, and must have been one of his most important contributions to her career.

Ritman was just one of a very large number of American artists who spent summers in that French town. Like Ritman, many of them emulated Monet’s impressionist style; others went further and adopted his entire rural lifestyle when they returned to the United States. Thus, in the late nineteenth century, enclaves of impressionist painters were established in numerous locales on the East Coast, some of which had been fishing or farming communities but were bypassed by industrialization and subsequently languished, as Vétheuil had in Normandy. Often centering on an influential teacher, these artists’ colonies provided the same amenities found in Giverny: affordable lodgings, a landscape untouched by industrialization or from which the vestiges of modernity could be excluded when pictures were made of them, and a vernacular culture that could be mined for picturesque motifs.12 The equivalence between the French and American colonies was articulated by Brooklyn-based artist and publisher Hamilton Easter Field in 1913 when he admonished visitors to Ogunquit, Maine, where he ran a summer art school and put up practicing modernist artists in old outbuildings: “Open your eyes wide, get the local tang. There’s as much right here in Maine as there is in Monet’s Normandy. But to get it you must live in touch with the native Ogunquit life, just as Monet wears the sabots and peasant dress of Giverny.”13

Joan Mitchell gardened, Kelly tells us, but she hardly pretended to be a local. Nor did she paint en plein air as Monet did at Vétheuil, typically positioning himself on the opposite shore of the Seine in the village of Lavacourt so that he could frame the grouping of Vétheuil’s buildings with the church of Notre-Dame at its apex.14 Nevertheless, according to an interview she gave in 1982, Mitchell thought of Monet’s landscape at Giverny as her “secret garden,” where, during the 1970s, she would meet up with friends to explore, before the house and grounds were restored to become the global attraction they now are.15 Painter Bill Scott recalled how Mitchell described having visited the gardens at Giverny, subsequently painted her version of a “most beautiful late Monet water lily,” and then scrubbed it out. This anecdote, retold by Kelly, shows how uncomfortable Mitchell’s relationship with Monet was by 1980: as attracted as she was to his aesthetic, embodied in both his paintings and his gardens, she resisted it.16 Still, the lyricism, beauty, and vibrancy of Mitchell’s monumental paintings seem perfectly at ease alongside the late Monets she admired as a young woman. Indeed, the pairings of Mitchell and Monet in the recent exhibitions go well beyond the garden variety critical analysis that Virginia Woolf satirizes in To the Lighthouse (1927) as “the influence of somebody upon something.” Instead, these magnificent canvases on which paint registers the gestures of artists who lived almost a century and worlds apart but on the same spot, together demonstrate what can happen when an artist settles into a quiet backwater for the long haul.

Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape will be on view at the Saint Louis Art Museum from March 25 to June 25.

1 Claude Monet to Hyacinthe Murer, quoted in Susan Grace Galassi, “Frozen Splendor: Monet’s Vétheuil in Winter,” in Olafur Eliasson and Galassi, Monet’s Vétheuil in Winter (New York: Frick Collection, 2022), p. 19. 2 Ibid ., pp. 19, 21. 3 Simon Kelly, “A Dialogue with Monet: Mitchell’s Years in Vétheuil,” in Monet/Mitchell: Painting the French Landscape, ed. Simon Kelly (Munich, Germany: Hirmer, 2023), p. 61. 4 Suzanne Pagé et al., Claude Monet, Joan Mitchell (Vanves, France: Hazan and Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Musée Marmottan Monet, 2022). 5 Monet/Mitchell was organized through a partnership with the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris; Joan Mitchell Retrospective was co-organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the Baltimore Museum of Art (BAM), together with the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Mitchell is not the only contemporary artist to be paired with Monet: the Frick Collection recently (October 20, 2022–January 23, 2023) installed a “diptych” consisting of its Monet, Vétheuil in Winter (1878–1879) and a recent work by Olafur Eliasson, Colour Experiment no. 109 (2020). 6 Interview with the author, January 12, 2023. 7 Patricia Mainardi, “Looking Forward to the Nineteenth Century,” lecture at the Morgan Library Museum, New York, 2007. Monet at Vétheuil: The Turning Point was shown at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor (January 25–March 15, 1998); the Dallas Museum of Art, (March 28–May 17, 1998); and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (May 30–July 26, 1998). The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue: Annette Dixon, Carole McNamara, and Charles F. Stuckey, Monet at Vétheuil: The Turning Point (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1998). 8 Kelly, “A Dialogue with Monet,” p. 16. 9 Galassi, “Frozen Splendor,” p.57. 10 Kelly, “A Dialogue with Monet,” p. 16. 11 Suzanne L. Epstein and Joel S. Dryer, “Louis Ritman (1889–1963),” n.d., Illinois Historical Art Project, available at illinoisart.org. 12 H. Barbara Weinberg, Doreen Bolger, and David Park Curry, American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885–1915 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), pp. 95–98. 13 Hamilton Easter Field, The Technique of Oil Paintings and Other Essays (Brooklyn, NY: Ardsley House, 1913), p. 58. 14 Galassi, “Frozen Splendor,” pp. 30, 32. 15 The house and gardens of Monet at Giverny opened to the public following a three-year restoration in June 1980, the year the Fondation Claude Monet was established to operate the site. See “Historique,” at fondation-monet.com. 16 Kelly, “A Dialogue with Monet,” p. 37.

KEVIN D. MURPHY is the Andrew W. Mellon Chair in the Humanities and Professor and Chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Vanderbilt University.