New York City has long been the artistic and musical heart of the nation, its cutting-edge position grounded in the opulent era known as the Gilded Age. Those decades following the Civil War were a time when the high noon of steam power and gaslight gave way to the dawning of electricity, as extraordinary inventions by Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell revolutionized communication, and as Elisha Otis’s safety elevator encouraged New York’s architects to reach for the skies. It was a time when a younger generation of American artists—women as well as men—found New York the perfect locus in which to embrace new ideas and ideals.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s intimate and often revelatory show, New York Art Worlds, 1870–1890, examines this sumptuous yet innovative period in the city’s history through the art it produced. The show has been organized by Sylvia Yount, curator in charge of the Met’s American Wing, and Thayer Tolles, curator of American painting and sculpture. It features some fifty works drawn from the Met’s American collections, each created by artists based in New York, or who exhibited in the city during this significant era in America’s artistic development. These paintings, sculptures, watercolors, illustrated books, and decorative objects attest to the rising sophistication of American artists whose contributions to the modernity of the New York art world at this time lay the foundation for the cultural capital it is today.

Post-bellum New York was a burgeoning city, though at this period—before the consolidation of 1898 annexed the former independent city of Brooklyn, neighboring Queens County, the Westchester district of the Bronx, and distant Staten Island—New York City was essentially confined to Manhattan Island. Until the 1870s, the focal point of New York’s artistic community had been the National Academy of Design, then housed in a Venetian-Gothic style palazzo facing Madison Square at East 23rd Street, where the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower now stands. Founded in 1825 by a group of young artists headed by the rising young painter Samuel F. B. Morse, it was modeled after the Royal Academy in London and aimed to foster a high standard of American artistic professionalism. The National Academy school provided traditional academic training—focused on drawing casts of classical sculptures—under the supervision of established professionals. Moreover, it sought to publicize and support a contemporary art market by holding annual exhibitions of new work.

National Academy exhibitions were regarded as equivalent to the annual Royal Academy exhibitions and the Paris Salon. Yet, after the Civil War, a new generation of Americans arrived on the scene, many having studied abroad. Upon returning home they found the new stylistic principles they had absorbed in Europe at odds with what they deemed the National Academy’s conservatism. Instead, the youthful members of this “new movement,” as it was commonly called at the time, embraced looser, modern European conceptions of what qualities constituted a finished work of art. Turning away from the majestic rhetoric of the Hudson River school landscape, they embraced figure painting and genre subjects founded on daily, often urban, life. Seeking new educational directions and exhibition venues, they founded the Art Students League in 1875 and, two years later, the Society of American Artists.

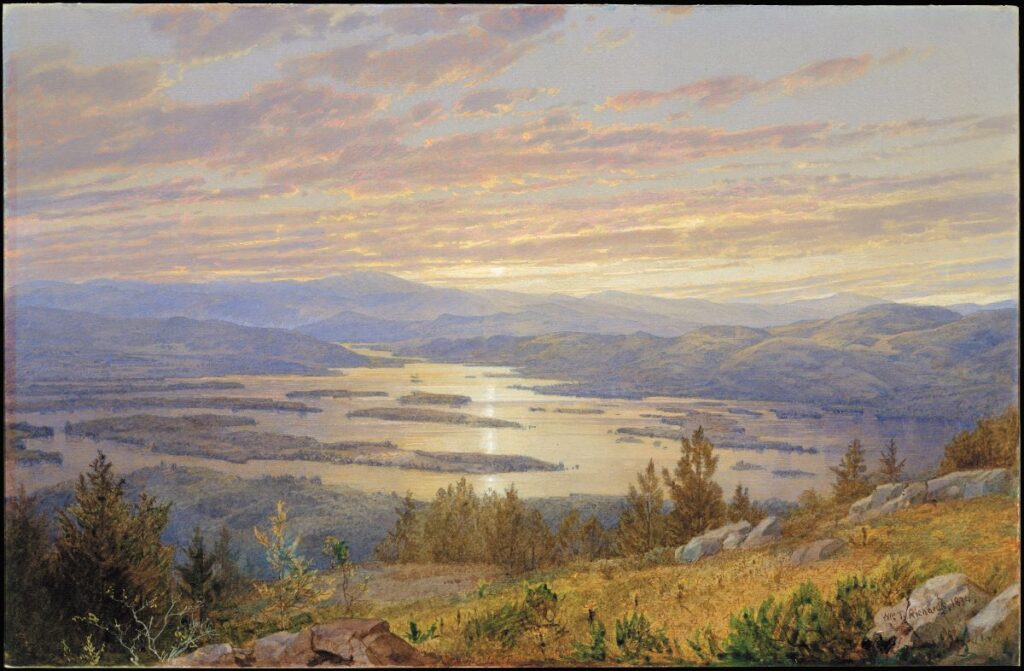

Even earlier, the American Society of Painters in Water Colors (now the American Watercolor Society) was founded in 1866 to raise the status of watercolor from a medium for amateurs and colorists of engravings to a serious professional medium. William Trost Richards, though Philadelphia-based, was an early exhibitor at the society, and the moving radiance of his Lake Squam from Red Hill (Fig. 1), included in the show, makes abundantly clear why he was so influential in this arena.

Equally important, new-movement artists banded together, creating their own community of progressive spirits, which also included sympathetic critics and journalists willing to support their work in the popular press. Some, like author Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer (1851–1934), put their efforts behind specific young artists like Thomas Eakins and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. A group of portrait plaques by Saint-Gaudens in the show celebrates some of these warm relationships, personal and professional, that flourished at the time (Fig. 3).

Exhibition venues newly established outside the academic system provided new-movement artists with increased opportunities to show their work, as did the willingness of the recently organized Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire new artworks (often presented as gifts by the artists themselves) for its collections.

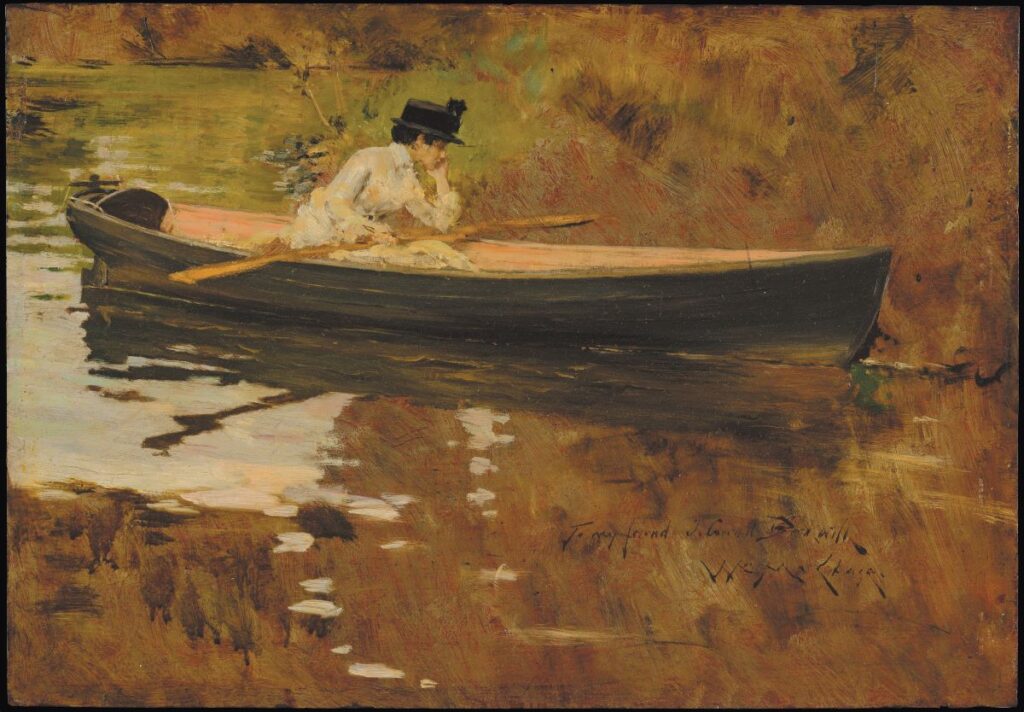

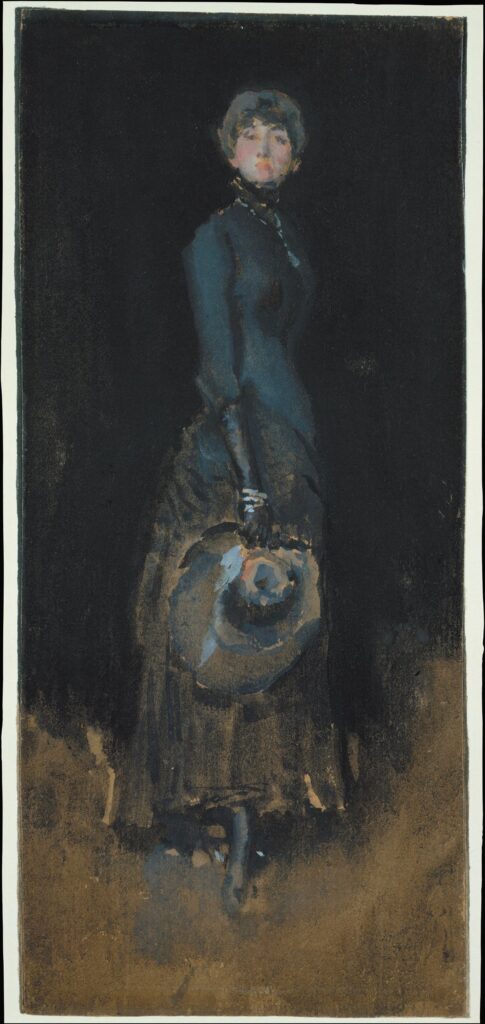

Once gathered professionally around an informal network of studios, schools, clubs, and commercial establishments surrounding Union Square, the artists represented in the show include familiar names like James McNeill Whistler, Winslow Homer, and great artist-teachers such as Eakins and William Merritt Chase. Several are represented by relatively unfamiliar works, including Whistler’s watercolor Lady in Gray (Fig. 4) and Chase’s oil Alice Gerson in Prospect Park (Fig. 2). Other works represent their many American contemporaries whose oeuvres have long been unjustly overshadowed. This latter group includes once-celebrated men like Edwin Austin Abbey, John La Farge, Francis Davis Millet, and Elihu Vedder as well as remarkable women like Edith Mitchill Prellwitz, Dora Wheeler (daughter of the more famous pioneering female interior designer Candace Wheeler), and Cecilia Beaux.

The show’s thematic arrangement subtly underscores late nineteenth-century aesthetic trends, and the selected works help to reveal these artists as tastemakers, organizers, exhibitors, and collaborators. Nevertheless, the chief pleasure here comes from examining the works themselves, for their pictorial qualities and painterly details and for the refined and often inventive techniques they embody. Among them are several paintings that depict actual New York scenes of the time, like Edith Mitchill’s beautifully atmospheric The Elevated (Fig. 5).

Mitchill (later wife of the gifted symbolist painter Henry Prellwitz) shows an “el” train of wooden coaches being pulled by one of the little Forney steam locomotives that hauled them before the electrification of the lines in 1903. Mitchill shows the train headed by a locomotive running in reverse, with the coal bunker leading. With calligraphic brushwork she deploys a subtlerange of pinks and light blues, lyrically enhancing the billowing clouds of steam and soot produced by these engines, which quickly darkened the surrounding buildings, just as the shadowy el structures darkened the streets below.

Among the landscapes representing differ structures darkened the streets below. A mong the landscapes representing different facets of the new movement is Albert Pinkham Ryder’s The Bridge (Fig. 7), an imaginative panoramic capriccio moodily combining the stone-arch High Bridge (completed in 1848)—which carried the original Croton Aqueduct across the Harlem River from the Bronx to northern Manhattan—with a portion of the skyline as seen from Central Park, features geographically distant from one another that would not both be visible from a single viewpoint. Ryder painted The Bridge on gilt leather, possibly to decorate a piece of furniture, hence it is one of his few surviving works of applied arts. He probably created it for the Fifth Avenue furnishing gallery of Cottier and Company, run by the enterprising Scottish designer-dealer Daniel Cottier, who engaged various artists to produce cabinetry, stained glass, and other decorations for the carriage trade.

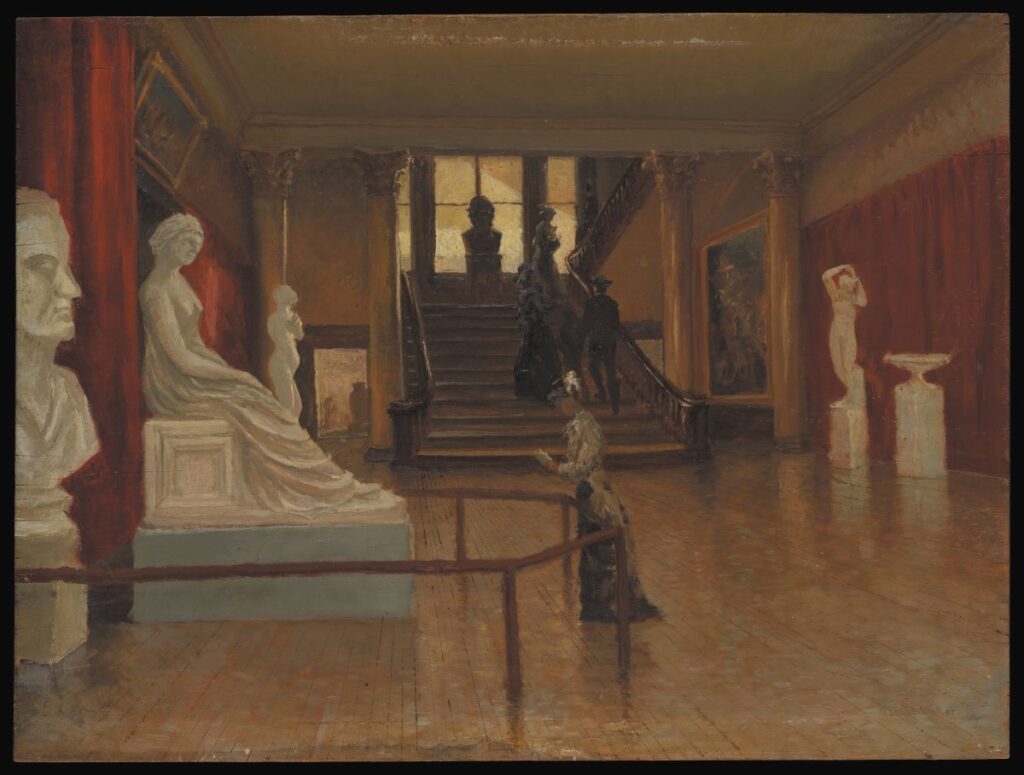

More interesting as a document rather than for its painterly finesse is Frank Waller’s oil on wood Entrance Hall of the Metropolitan when in Fourteenth Street (Fig. 6). It shows the spacious entrance hall and broad staircase of the Met’s second temporary home, the former Douglas mansion, a substantial brownstone house located on Fourteenth Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, where it would remain until the move to Central Park in 1879. Having made earlier drawings on site, Waller painted two views of the Douglas mansion quarters. (The other one, also dating from 1881 and in the Met’s collection, though not included in the show, depicts a gallery on the second floor filled with paintings.) His view of the entry hall emphasizes the sculpture collection, with marbles displayed around the foyer and on the landing of the staircase. A fashionably attired woman consults her guidebook while viewing William Wetmore Story’s 1873 marble of Polyxena, the mythological Trojan princess beloved of Achilles. Story’s sculpture now belongs to the Brooklyn Museum.

Waller studied commercial art at the New York Free Academy (now the City College of New York) and pursued that field professionally while painting in his leisure hours. After studies in Rome and a tour of Egypt (subject of his pleasant orientalist scenes), he studied at the National Academy before becoming a founder and first president of the Art Students League.

Two paintings in the show notably record artistic life at the time. German-born Louis Lang’s detailed Women’s Art Class (Fig. 8) documents the advancing opportunities for women to receive training in a professional studio. Where women were formerly limited to private drawing lessons from a tutor or a professional artist as part of a respectable female education, schools like the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (founded in 1859) offered the opportunity for them to study together, like the men, if not actually with men. In Lang’s painting a pleasantly industrious atmosphere prevails: as one woman works with a compass to copy a measured architectural drawing, behind her another in yellow shows her profile study to a colleague painting a landscape. A third models a clay or plaster bust. Swagged with elegant green portieres, the studio itself seems well illuminated by a skylight, its walls crowded with plaster casts, art materials and pictorial reference works strewn about.

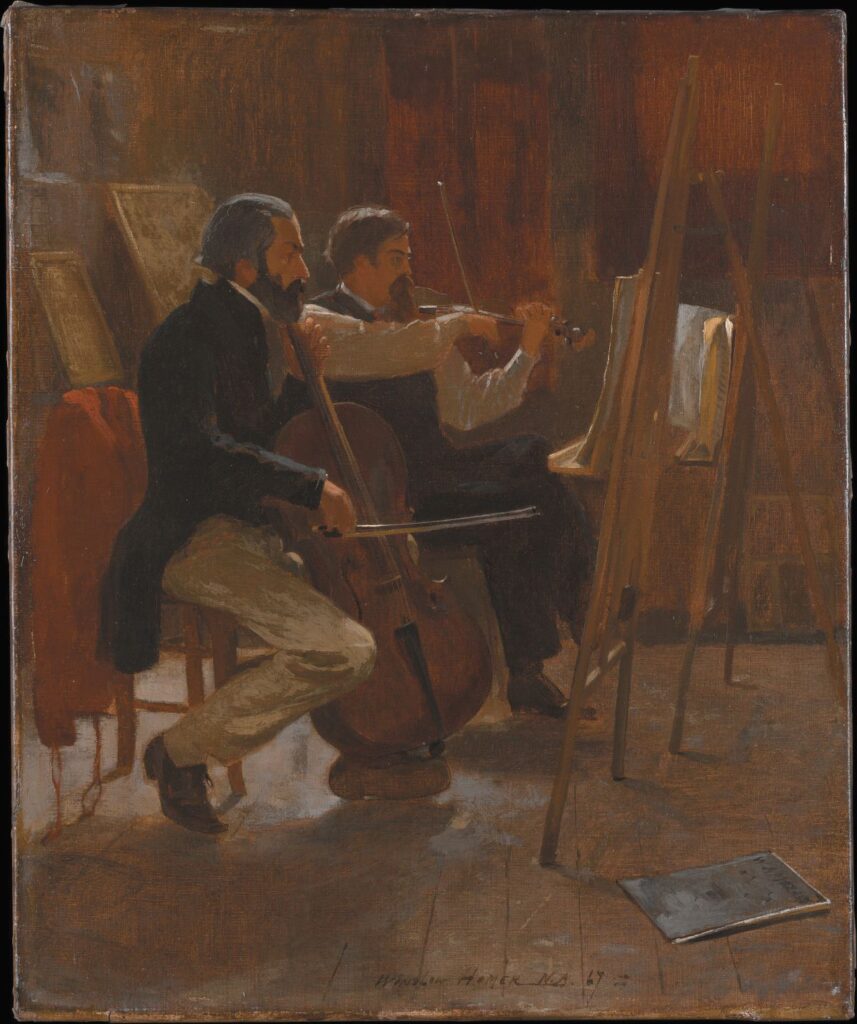

Homer’s charming The Studio (Fig. 12) shows the cultural pursuits that were common among artists when not actually at their work— here two painters enjoy a musical moment together playing a duet for violin and cello, reading from sheet music propped on their easels. In the lower right corner a large folio is clearly marked “W. A. Mozart.” The consciously bohemian scene evokes the many musical reminiscences forming the backdrop to Punch cartoonist George du Maurier’s bestselling novel of Second-Empire Parisian artistic life, Trilby (published serially in 1894 and in book form in 1895). In a time before the development of the phonograph industry, musical training was considered fundamental to a genteel life and many nineteenth-century artists were accomplished amateur musicians, most notable among them John Singer Sargent, whose musical ear was as acute as his painterly eye and whose pianistic abilities were deemed of a professional level.

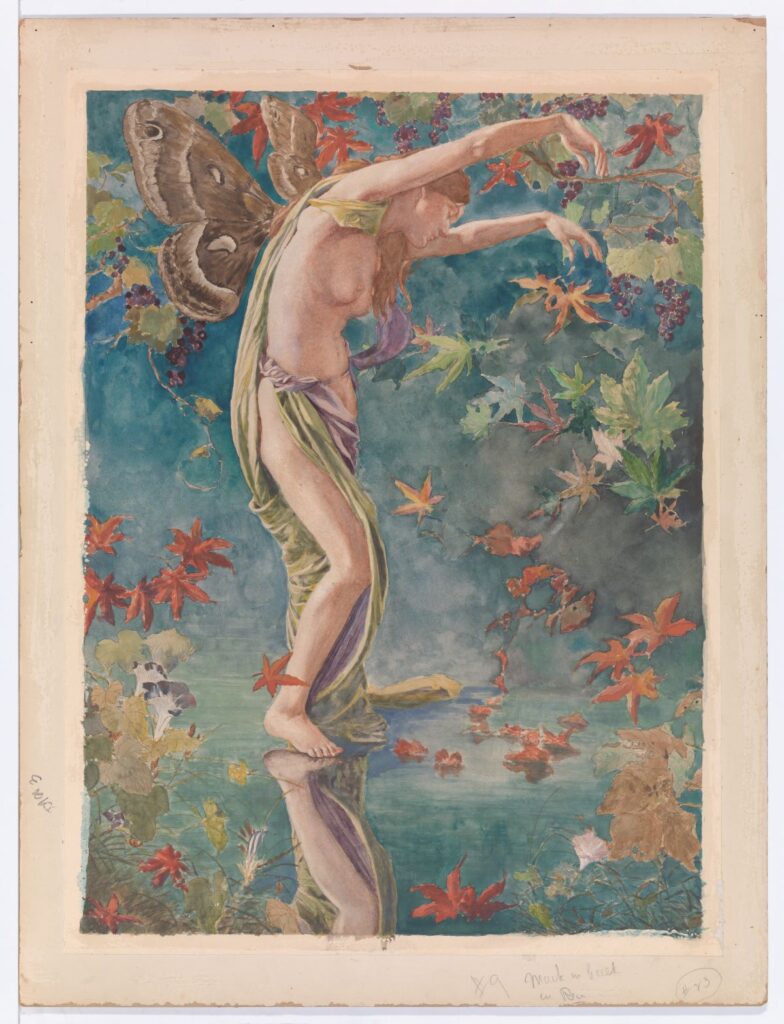

Examples of stained glass by, respectively, John La Farge and Louis Comfort Tiffany recall their rivalry in this decorative field. La Farge produced his allegorical watercolor Autumn Scattering Leaves (Fig. 9) as a proposed stained-glass window design. When his patron rejected it in favor of a neoclassical alternative, La Farge exhibited it as an independent work. The terpsichorean pose of his sensual winged nude figure poised upon the glassy surface of a stream prompts one to wonder if La Farge based the figure on one of the many sketches he made of native dancers during his extended 1890–1891 voyage to the South Pacific with his great friend, historian Henry Adams.

Longtime colleagues whose friendship dated from their years in the expatriate artist colony in the English village of Broadway, Edwin Austin Abbey and Francis Millet were important figures on both the American and British scenes. Abbey—who became a major Shakespeare painter and an important muralist (his series The Quest of the Holy Grail is one of the decorative masterpieces of Charles McKim’s Boston Public Library)—was busy as an illustrator of books and stories and articles in Harper’s Magazine. In his unfinished watercolor The Hat with the Blue Ribbons, the sitter’s vaguely colonial costume and the turned spindles of the Morris and Company “Sussex” armchair deliberately evoke eighteenth-century rural life (Fig. 10).

Millet, who also enjoyed close friendships with Mark Twain and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (whose bronze profile plaque of Millet is in the show), was also a writer, sculptor, and muralist. Like Abbey’s watercolor, Millet’s charming genre painting A Cosey Corner (1884) evokes the romanticized antiquarian spirit of the colonial revival, which gained popularity after the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, at which one of the features was an eighteenth-century “New England Kitchen.” Millet apparently incorporated several features of the New England kitchen in his East Bridgewater, Massachusetts, studio, which, notes Yount, “he used as a kind of stage set for costume pieces like this one.”

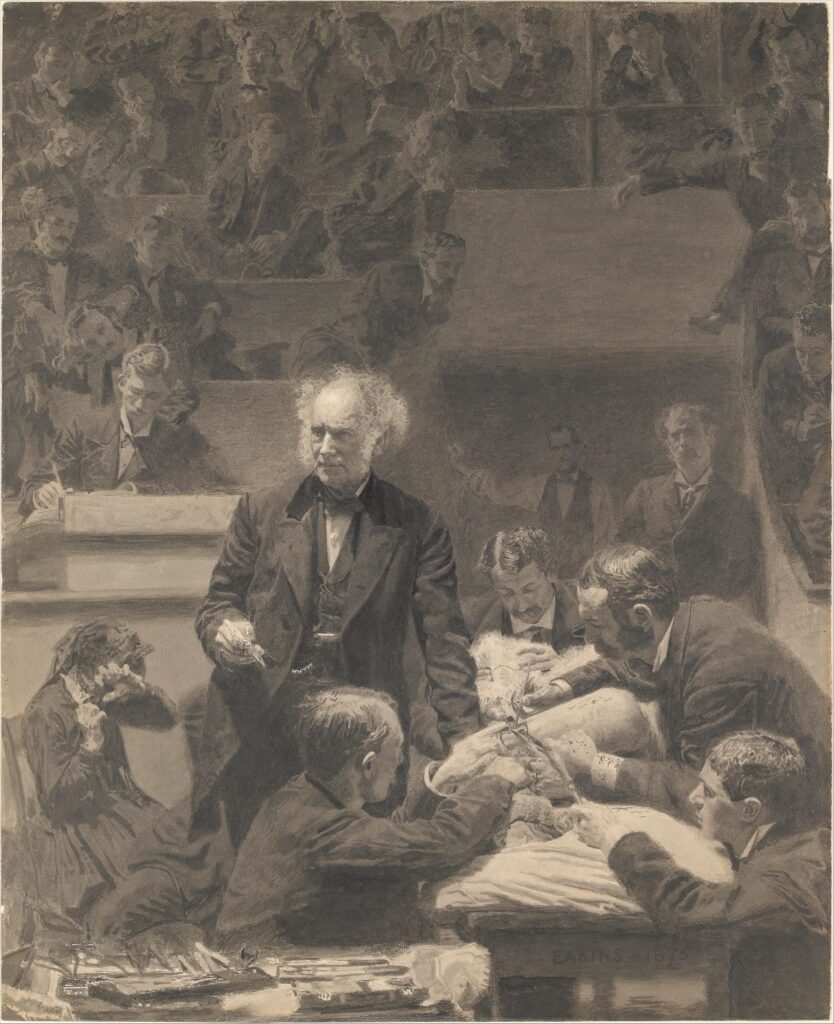

One of the show’s most exceptional works is Eakins’s India ink and watercolor The Gross Clinic (Fig. 11). A quarter-size reduction of his original oil portrait (jointly held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), it is a masterly work of draftsmanship, deliberately drawn for reproduction because Eakins did not trust a photograph of the painting to translate its color values into black and white. It attests to the pains that academically trained painters took to create a work, and in this instance to reproduce it for photomechanical printing. Most artworks were reproduced for printing by means of steel or wood engravings prepared by graphic specialists, and which usually printed the image in reverse. In this case the final collotype (an early form of photolithography) would print Eakins’s drawing from a photograph of it, without reversal, every line and shadow representing Eakins’s own hand rather than the intermediary hand of an engraver.

Asked what insights they hope visitors will derive from what Tolles characterizes as this “layered and textured look at Gilded-Age New York,” Yount replies that, “beyond understanding that this cultural moment was far more diverse and progressive than generally acknowledged, we hope visitors will realize how the era’s network of artistic, academic, and commercial organizations yielded a variety of art forms aimed not only at traditional elite patronage, but to the increasingly influential middle class. Moreover, it created opportunities for a range of practitioners (US-born and immigrant)— including women and a handful of artists of color.”

New York Art Worlds, 1870–1890 is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to July 21, 2024.