For both breadth and depth, the collection of early English needlework amassed by British business executive Percival D. Griffiths (1862–1937) was the most important assemblage of such material built in the first half of the twentieth century. He displayed vast quantities of it at his Hertfordshire country home, Sandridgebury, where it took pride of place on the walls of all the main rooms, and impressed visitors no less discerning than Queen Mary. Griffiths was only the most prolific of several important collectors who, by gathering together, exhibiting, and publishing these objects as significant examples of English decorative arts, removed a long-standing stigma surrounding their artistic merit. Long dispersed, the collection has been reconstructed in Volume II of the monograph dedicated to Griffiths’s works of art, English Needlework, 1600–1740. In the following excerpt from the book, author William DeGregorio explains how these objects underwent a transformation from “grotesque” embarrassments to “glorious” treasures, to be appreciated for the information they provided on a lost way of life and the women who lived it.

An early step in needlework’s reappraisal as an art form was the Exhibition of Old English Tapestry Pictures, Embroideries and Samplers of 1900, organized by the former editor of the Art Journal, Marcus B. Huish, at the Fine Arts Society in London. As he wrote in the large illustrated catalogue that appeared later that year, popular interest in the exhibition was extraordinarily high, precisely because “almost every visitor possessed some specimen of the craft, but few had any idea that his or her possession was the descendant of such an ancestry, or had any claim to recognition beyond a quite personal interest.” Only when needlework was removed from its domestic context and viewed en masse did the public begin to accept its value. It took a “museological” approach to elevate estimation of this material, and Huish cited no less an authority than John Ruskin in arguing for needlework’s fundamental place in the English museum landscape. The Illustrated London News hoped that the “publicity thus given to the primitive phase of our national art may draw other specimens from their hiding-places.”

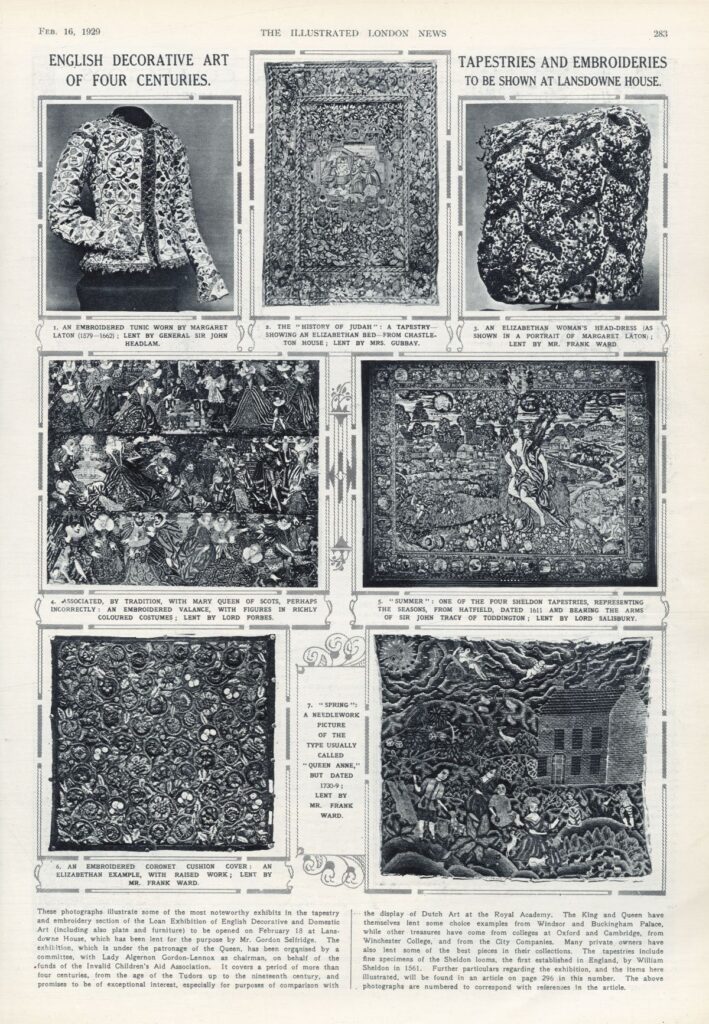

Subsequently, in a fulfillment of this wish, the numerous exhibitions that showcased English needlework in the interwar period (1919–39), often staged for charities, brought together large quantities—up to 600 pieces in some cases—of embroidery, impressing the public with the sheer mass and brilliancy of this material. Typically viewed in sometimes sad country-house contexts, domestic needlework of the seventeenth century did not have a stellar artistic reputation. However, the needlework caskets (Fig. 1), baskets (Fig. 4), framed panels (Fig. 5), and trinkets (Fig. 6) collected by Percival Griffiths, Sir William Burrell, William Hesketh Lever (Lord Leverhulme), Sir William Plender, Sir William Lawrence, Frank Ward, and Sir Frederick Richmond were carefully chosen to be the best of the best in connoisseurial terms, and when these objects were presented in large numbers—often with the endorsement of the omnipresent exhibition patron Queen Mary—their reputation and interest steadily grew.

On the occasion of the Loan Exhibition of English Decorative Art at Lansdowne House in February 1929, the London Times highlighted the importance of collectors in safeguarding these treasures, which were normally kept in “a less crowded atmosphere, where their charms, perhaps, are so well known that there will often be days, perhaps even weeks, when no one will consciously look at them at all.” Indeed, The Times was particularly fulsome in its praise of this exhibition, and the power of its needlework pieces to invoke a powerful emotional response. In an anonymous editorial that appeared just after the exhibition closed, it lamented that the “rare and delicate creations of human hands” on display, having “delighted our eyes and stirred our memories,” were destined to be returned to their owners, and to disappear once more from public view. Vivifying her portrait, the newspaper wrote that, “Mme. Margaret Laton of Rawdon, together with her embroidered tunic, ‘mainly in button hole stitch,’ must be content once more with a smaller circle” (Fig. 7). The reviewer singled out one of Sir Frederick Richmond’s loans, an embroidered casket dated 1678 and initialed “E C,” grieving over how “the animals and the flowers which ‘E.C.’ caused to prance and to bloom in such a delicate profusion, even the mermaid, will fade from the memories of all but the enthusiasts, and await in the wise care of their owners the next burst of applause.” In describing the power of the objects on display to conjure and reanimate historical figures within the imagination of the spectator, he added:

Yet those who do pause to remember [the exhibition], those to whom such things as Jacob Lord Astley’s gloves, or Charles II.’s deed-box, or the embroidered case containing Sir William Walrond’s love letter of October 27, 1659, to Diana de Montpellon, are more than materials, will be permanently enriched by this leisurely sight of them. For here all the matters of romance have been gathered together; all the gracious and artful devices for the adornment of life, so that the eye may see beyond the lines and curves of chairs, commodes, and tables; inside the caskets and the letter-cases, between the coloured splendours of the arras, into the lives of those who planned, wrought, and used these things. To such the gloves of 1600 have been but freshly drawn from the hands; Oliver Cromwell has this day worn his christening robe; the bitter tragedy of Charles I. (how strangely symbolized in the reunited Garter ribbon) draws on apace; William III. is even now pausing in his work to give the two-handled cup to his god-daughter, little Dorothea Manly; Peter Garon is bending over the fine mechanism of his eight-day striking clock, and, faintly far off in 1700, a fair unknown is still awhir at her spinning wheel. Herein lies a charm; whether each object is linked to a known first owner or whether it is a bit of nameless lovely work adrift in the world, each has at some time received personality. The expert may discuss the texture of the tapestries, the variety of the stitches in the needlework, or the excellence of the carpentry. He may ascribe authorship to this and exact period to that. But only when he is also a lover will he give his pupils true proportion in these matters. For in looking at these treasures, collected from so many sources, we see their beauties enhanced. Pages of history start again into movement about them, and memory and vision unite in lighting up the stage peopled with great, with simple, and with kindly shapes.

Why did collectors like Griffiths, and the general public, become infatuated with the arts of the Stuart period (Fig. 8)? The introduction to an article of 1930 about the collection of Major Cyril Sloane-Stanley by Basil S. Long, then keeper of paintings at the V&A and an expert on miniatures, goes some way toward explaining the contemporary interest in the Stuarts:

A curious glamour surrounded the Stuarts, that family “plus infortunée encore qu’illustre, qui avait rempli le monde du bruit de ses malheurs,” and it still to some extent pervades their memory. The romantic career of Mary, Queen of Scots, the early promise of Prince Henry, cut off in 1619 at the age of eighteen and now almost forgotten, the tragic fate and courageous end of Charles I and the early part of “Bonnie Prince Charlie’s” life appealed especially to the popular imagination. Charles II, the cynical viveur, was no hero, but somehow makes a sympathique figure. James I, James II, and the “Old Pretender,” however, have no advocates, and Queen Anne is hardly remembered except for the fact of her death and for the style of furniture evolved during her reign.

From the mid-nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth, a veritable obsession with Mary Queen of Scots had developed, fostered and promulgated by numerous antiquarian exhibitions, which purported to display objects associated with the tragic queen, who famously occupied her time, while confined, with needlework. Numerous gloves, shoes, veils, and other items worn or used by the queen were shown, but it was objects supposed to have been “worked” by Mary herself that most directly forged a link with the past.

Griffiths collected no needlework with connections to Mary, but he did have a passion for images of Stuart monarchs, from Charles I to James II, and he collected later Jacobite material as well. When trying to sell some of her late husband’s embroidery to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1938, Mrs. Griffiths pointed out the rarity of the embroidered portrait of Charles I that had been offered (Fig. 10), writing: “Percy had 5, and when Queen Mary saw them she said, ‘Where did you ever find five of these[?] I have only been able to get two!’” This obsession with royal portraiture in needlework sometimes led Griffiths to create fanciful interpretations of iconography; he believed, for instance, that the scene on the lid of a stumpwork casket dated 1662 represented “a Toast to Charles 2nd on coming into his own,” as he recorded in his album (Fig. 9); in fact, it represents King Ahasuerus and Haman at Esther’s banquet (Fig. 9a).

If the insinuation of feminine dutifulness and devotion to monarchy in these needle-works was admirable, so too were the aesthetics of the Stuart style, which was appreciated both for its soft color palette and lively figurative quality. A persistent strain of stylistic conservatism—a reaction to the avant-garde artistic movements of the fin de siècle—influenced this interest in the naive forms and subtle colors (caused by fading) of the seventeenth century. Indeed it was precisely the soft, pastel colors of sun-washed embroidery threads that many found attractive. A notice of the Fine Art Society’s Exhibition of Old English Tapestry Pictures, Embroideries and Samplers in 1900, for example, attributed the “charm” of seventeenth-century needlework pictures to “the kindly hand of Time, in softening and harmonizing” the colors. In 1921, on the occasion of The Franco-British Exhibition of Textiles at the V&A, The Times reported that the current interest in Jacobean embroidery, and in imitations thereof, which had begun before World War I, was attributable to “The sober browns, blues, and greens in which flowers, leaves, and birds are carried out”—tones that viewers found “satisfying and quiet” (Fig. 11).

Authentically old pictorial embroideries, however, retained a particular decorative purpose. As The Times also reported at the time of The Franco-British Exhibition, many embroideries were “hung, as pictures are hung, for decoration.” Indeed, Griffiths, along with other collectors like Lever, used needlework as a substitute for paintings in their homes, adorning the walls with framed pictorial panels and sometimes even costume accessories (Fig. 12). As opposed to the stiff hieratic portraiture of the Tudor period and the allegorical monotony of seventeenth-century court paintings, scholars and collectors sought a connection with everyday life in early modern England through needlework. The lens through which twentieth-century enthusiasts viewed this England was bifocal. On one hand, a sense of (usually feminine) moral character—both of the makers and of women generally—could be deduced from the mere fact of stitches on canvas, whether the subject was figurative (usually biblical) (Fig. 13) or merely decorative. On the other, a more direct representative expression could be found in scenes thought to signify typical pastimes, relationships, and architecture (Fig. 15), or, alternatively, in the exploration of archaic object forms such as caskets, purses, baskets, and gloves, which embodied certain ideals of social and domestic coherence (Figs. 2, 14). The desire was to reach across the gulf of industrialization to grasp the tangible proof of a pre-modern domestic life centered on harmony, order, and piety, if nevertheless interrupted by the epoch-defining dramas of the Civil War and Commonwealth.

This article is excerpted and adapted from English Needlework, 1600–1740, The Percival D. Griffiths Collection (Vol. II) and all notes and sources for this excerpt can be found in the book. Both that book and English Furniture 1680–1760, The Percival D. Griffiths Collection (Vol. I) are available from Yale University Press.