In his 1948 year-end report, Charles Kuhn—Harvard professor, curator of the university’s Germanic Museum (later called the Busch-Reisinger Museum), and recently discharged deputy chief of the soldiering art experts known as the Monuments Men—took the modest first step to establish an archive of Bauhaus materials. “One of the most important of the projects planned for the future,” he wrote, “is the assembly of study material related to the Bauhaus, which flourished in Germany from 1919 to 1933. This school of design has an enormous influence on American architecture and industrial art and the presence, at Harvard, of a study collection will be of great service to future historians.”Working from names provided by Walter Gropius, Bauhaus founder and then chairman of Harvard’s department of architecture, Kuhn sent thirty-one letters to faculty members, students, and associates who had emigrated to America. Starting with four hundred objects and a small selection of work by Klee, Kandinsky, and Feininger which he purchased before the war, he launched the Harvard collection which has grown to over thirty-two thousand objects.

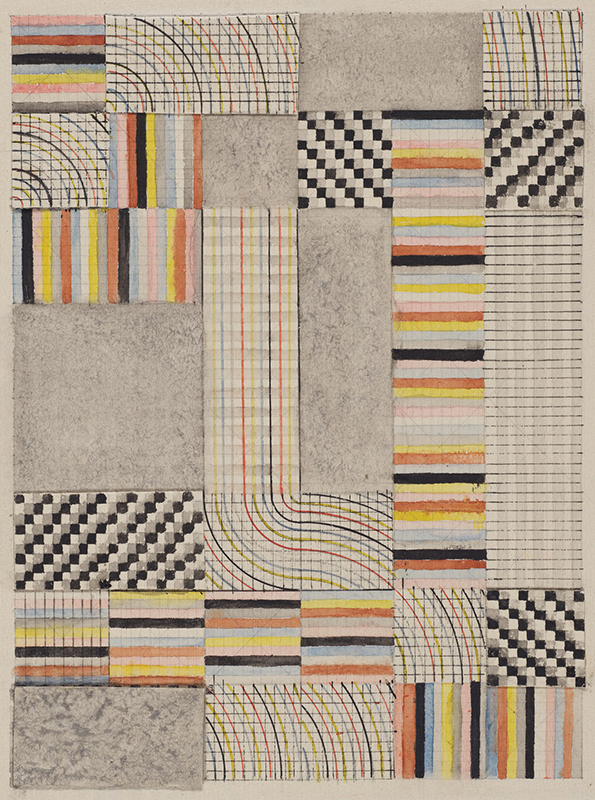

To mark the centenary of the opening of the Bauhaus, the new exhibition The Bauhaus and Harvard tells the story of the school’s own association with the movement with nearly two hundred assorted and often ravishing objects culled predominantly from its holdings. These include Anni Albers’s ebullient and labyrinthine design in watercolor for a rug; a handmade brass coffee and tea service by Wilhelm Wagenfeld; László Moholy-Nagy’s Light Prop for Mechanical Stage, still operational thanks to Harvard conservators; and Oskar Schlemmer’s geometric costume designs for the puppet-like figures in his Triadic Ballet.

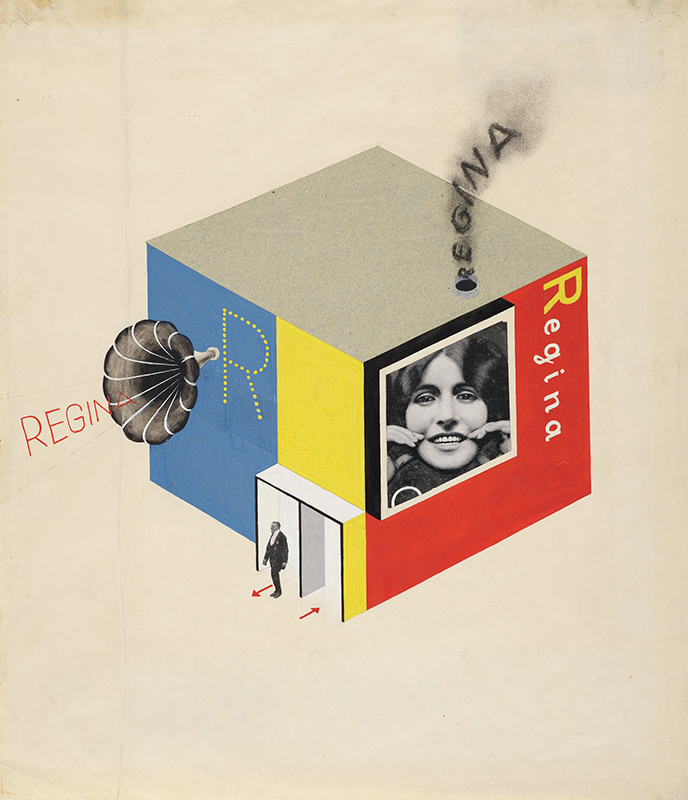

The show is anchored by two standout works by Herbert Bayer—the painter, sculptor, architect, and environmentalist best known for having designed the Bauhaus Universal typeface. One is his 1924 collage, Design for a Multimedia Trade Fair Booth, which epitomizes the exuberance of the early Bauhaus through the playful conception of a cube-like kiosk advertising Regina-brand toothpaste. The other is his monumental, twenty-foot-wide mural Verdure, once situated below a set of clerestory windows in the Harkness Commons dining room in the Harvard Graduate Center. The waves of color in the spectacularly lush abstract painting, Bayer explained, were meant to create a sense of perpetual unfolding and growing that was in synchrony with the natural world beyond the windows. With such simple considerations about the integrity of art in its architectural space, he transplanted the essence of the Bauhaus to Harvard.

The Bauhaus and Harvard • to July 28 • Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts • harvardartmuseums.org