In 1836 an anonymous review of modern paintings at the Royal Academy appeared in the conservative Blackwood’s Magazine. It was critical, even scornful of the artists who “delight in glare and glitter, foil and tinsel,” singling out J. M. W. Turner for special opprobrium. Young John Ruskin, Oxford man and amateur poet, dashed off a riposte. The review “raised me to the height of black anger in which I have remained pretty nearly ever since,” Ruskin recalled in his account of the moment, penned half a century later. Holding his tongue was out of the question. “[I had] by that time some confidence in my power of words.”

And what words! Perhaps no art critic writing in the English language has crafted so many pretty—and purple—passages. Here he is on Turner’s skies, one of his favorite subjects: “From the zenith to the horizon becomes one molten, mantling sea of color and fire; every black bar turns into massy gold, every ripple and wave into unsullied, shadowless, crimson, and purple, and scarlet, and colors for which there are no words in language, and no ideas in the mind.”

Ruskin would publish prolifically until his death in 1900, in the fields of art (five volumes of Modern Painters), architecture (The Stones of Venice and The Seven Lamps of Architecture), even a treatise on economics, Unto This Last, from which an encyclopedic exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, celebrating the bicentennial of the critic’s birth this year, takes its name.

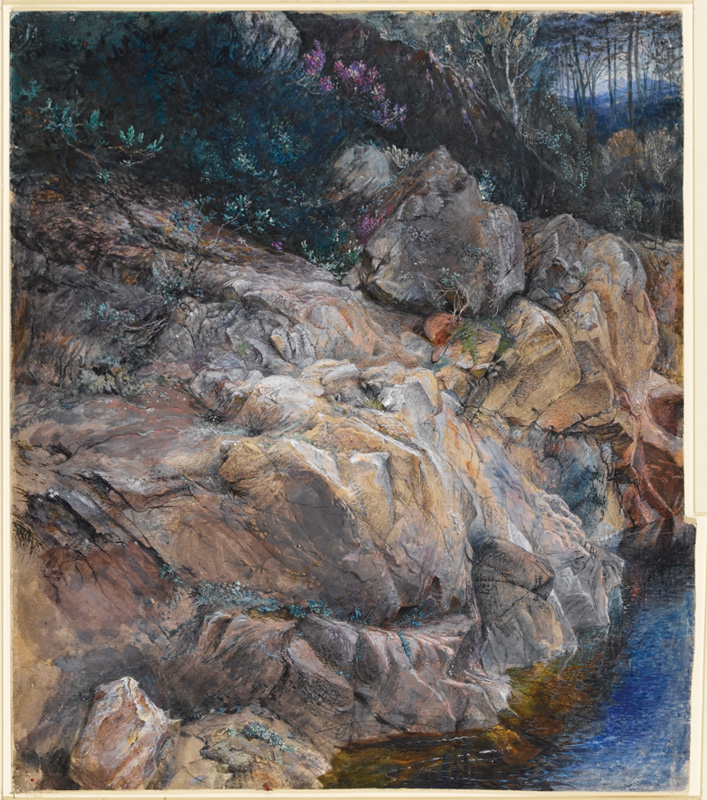

“His fundamental belief was that if you look closely at the world, it will reveal itself to you,” says Yale art history professor Tim Barringer, and the show takes visitors on a tour of the material Ruskin was influenced by, collected, and himself produced. This includes Turner’s Venice, from the Porch of Madonna della Salute (an exciting loan from the Met), an engraving of which hung in Ruskin’s Oxford dorm room; the critic’s copy of philosopher Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Inquiry; pen-and-ink and watercolor studies of rock formations natural (the stony banks of Scottish streams) as well as manmade (the cut, carved, and polished marble facade of the Basilica of St. Mark’s in Venice); and even stones themselves, in the form of Ruskin’s beloved mineral collection.

—Sammy Dalati

Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin • Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut • to December 8 • britishart.yale.edu