Francis Bacon: Late Paintings is suitable for emergencies both public and private. The Museum of Fine Arts Houston didn’t plan it this way, but to see Bacon’s work here, amid a worldwide pandemic, is to grasp how well the British painter understood us — our weaknesses, our cruelty, our despair, and frivolity. After closing temporarily due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the museum reopened on May 23. The Bacon exhibition has been extended through August 16.

Nearly 30 years after his death, Bacon’s lessons in nihilism and obsession retain their power to shock. Mere provocation was never his goal, however. His ambitions were bigger than that — and far less wholesome — as he made clear in an oft-quoted 1955 statement for the Museum of Modern Art: “I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail, leaving a trail of the human presence . . . as the snail leaves its slime.”

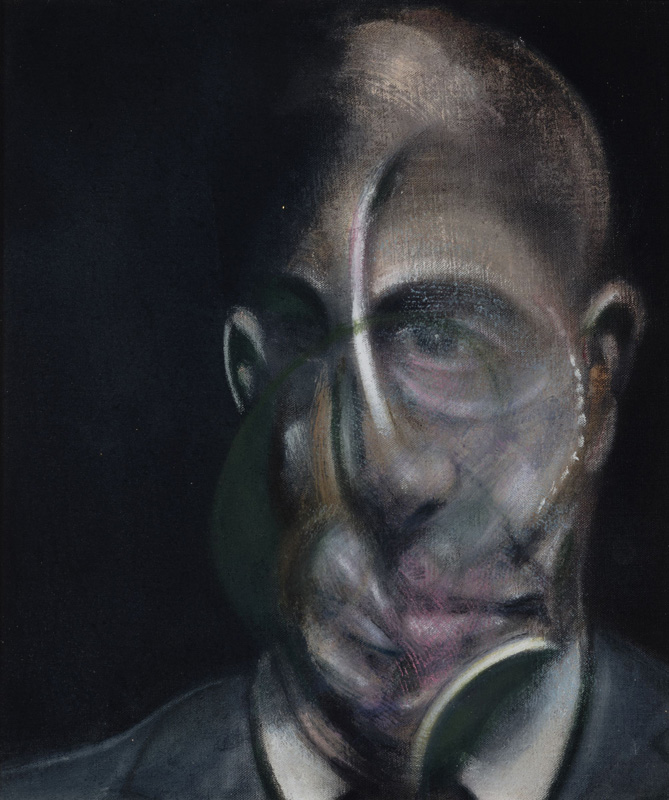

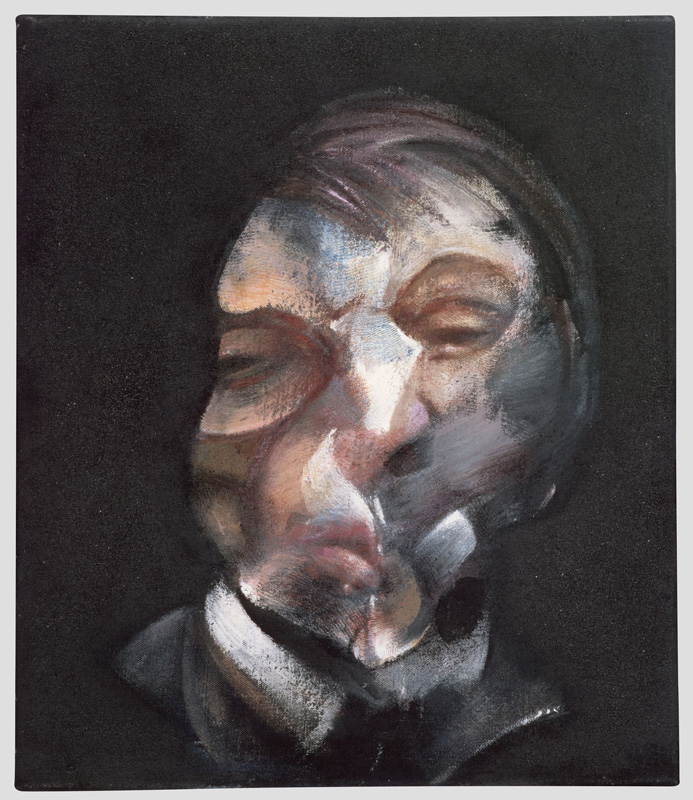

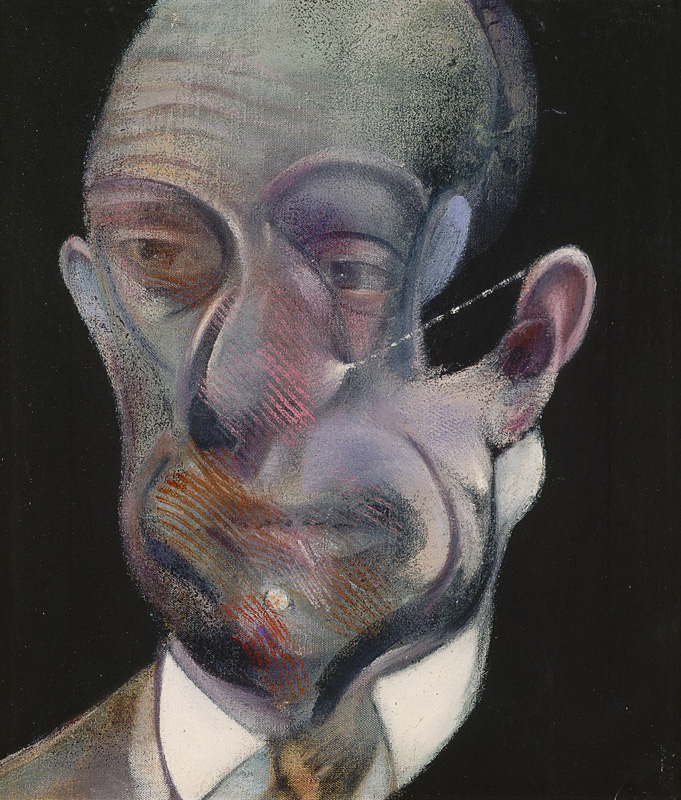

What Bacon made of the “human presence” comes through forcefully in Houston’s survey of 20 late-career masterworks: small portraits, moody landscapes and the vast, figurative triptychs that came to dominate his oeuvre. In every piece, one senses the steely nerve of a gambler who never lost his taste for existential dilemmas — a gambler who also embraced risk in his personal life, whether playing the tables through bleary nights at Monte Carlo casinos, plunging into rough trade encounters, or bingeing until dawn at seedy London clubs. He put it bluntly in an interview with critic David Sylvester: “I always think of myself not so much as a painter but as a medium for accident and chance.”

Immaculately hung in five spacious galleries, the exhibition traces Bacon’s evolution from shortly before the 1971 suicide of his lover, George Dyer, to the painter’s death in 1992. It’s a show that invites autobiographical readings: a tale of friendships, of withering self-regard, of the changes wrought by age and misadventure.

“You always love the show you’re hanging, but this one will surprise a lot of people who think they know Bacon’s work,” said MFAH curator Alison de Lima Greene. “The late paintings aren’t as well-known as his iconic early images — those screaming popes, for example. In this show you get more of Bacon’s meditative side. He didn’t need to hammer home his points anymore. His painting technique — all self-taught — had been brought to the highest pitch of refinement and his drawing skills were absolutely assured.”

The MFAH is the only tour stop for Francis Bacon: Late Paintings, which originated at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It opened at a booming time for Houston’s flagship museum, which, in a matter of weeks, also unveiled a grand touring show from New York’s Hispanic Society, and an exhibit that focuses on its own, comprehensive collection of radical Italian design — all while planning for the November 2020 opening of another museum building on its sprawling campus.

For the Texas show, the lineup of paintings has changed about 25 percent due to loan restrictions, Greene said. To tailor the show for Houston, she worked closely with museum director Gary Tinterow, who had curated a Bacon retrospective for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2009 — the last big show in the United States.

“Gary and I talked extensively about how to preserve the integrity of the Paris exhibition,” Greene said. “The Pompidou focused on Bacon’s literary influences — a theme especially suited to French audiences, which have a different, more intimate relationship with Bacon’s work. He lived, worked and exhibited in Paris for years.”

Bacon’s work evolved dramatically during the quarter-century covered by the MFAH show. In 1967, for example, he hit a mid-career high with Triptych Inspired by T.S. Eliot’s Poem Sweeney Agonistes — a Grand Guignol altarpiece built to accommodate two whores sprawled in sleep’s coils; a brutal S&M coupling; and a blood-spattered murder scene set on Le Train Bleu between Calais and the Côte d’Azur. Using an acid palette, Bacon deployed snaking brushwork and dripped paint amid geometric props, staging an extended dream narrative quite distinct from the claustrophobic freeze-frame of his early, single-figure canvases.

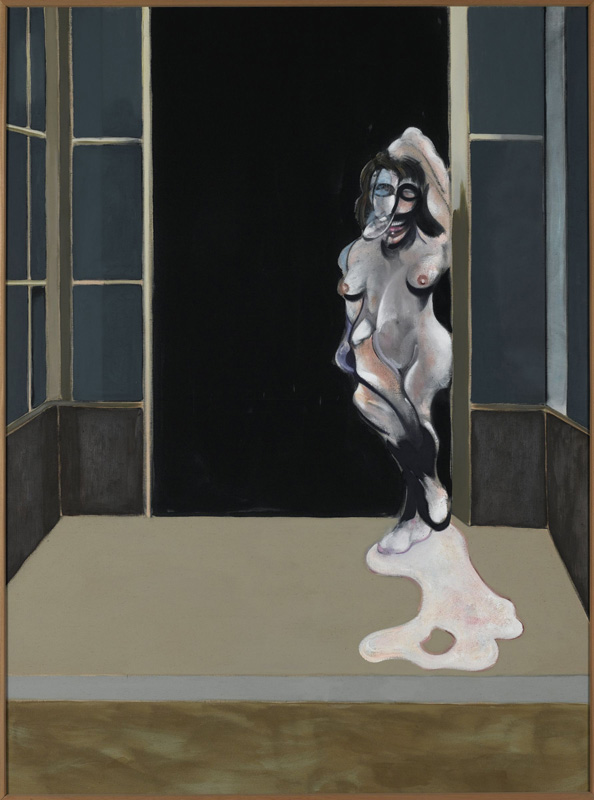

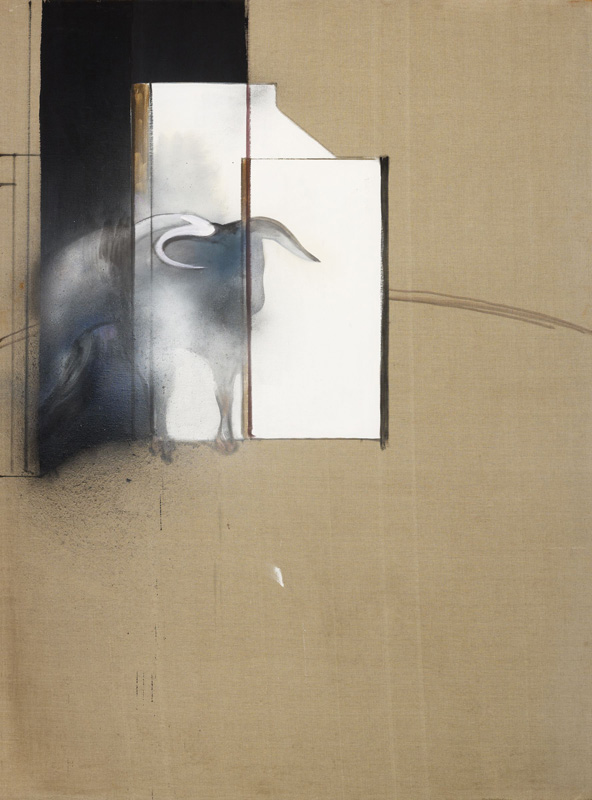

By his final years, the violence of Bacon’s images had abated, while the elements of his signature style remained — both his feeling for the expressive possibilities of the human form, and his desire to offer “sensation without the boredom of its conveyance.”

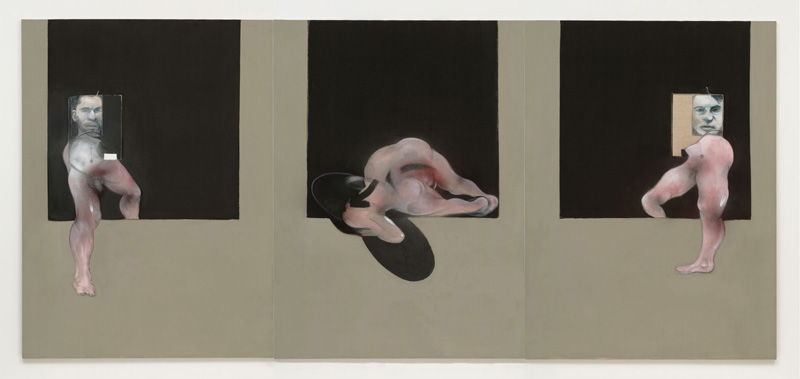

Resignation pervades Bacon’s late works. He knew that the end was coming, and found a potent emblem for death when he started to bind dust from his studio floor into impasto passages. His paintings changed in other ways, too. In the 1991 Triptych, loaned to Houston by the Museum of Modern Art, Bacon attains an elegiac calm. Here the undulant figures — Bacon and a lover— step from black portals that float on vast expanses of unprimed canvas. Between them, on the central panel, a mass of flesh spills over the lip of another black gateway. It’s a farewell to life and love, which feels about perfect for our current situation. Go see it when you come out of quarantine.

New Orleans journalist CHRIS WADDINGTON is a regular contributor to The Magazine ANTIQUES and other national publications. His many awards include two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships for critical writing.