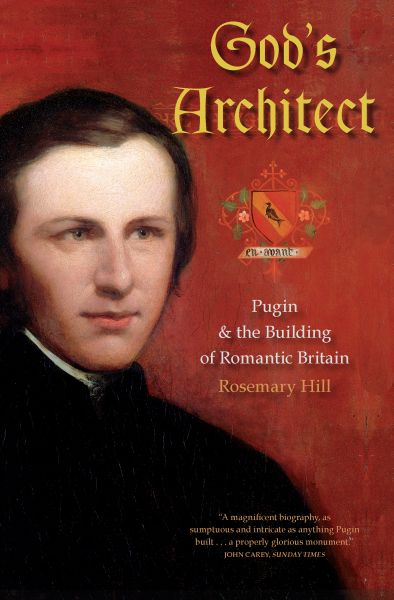

God’s Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain by Rosemary Hill (Yale University Press, 2009), an extensive biography of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852), won the Wolfson Prize for History and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Biography in 2007, when it was published in England. The book is recently published in the U.S. by Yale University Press. Hill, a writer and cultural historian in London, agreed to answer some questions for The Magazine ANTIQUES regarding this extensive and detailed biography:

A.W.N. Pugin seems to be catching a great deal of attention, thanks to you. What was there about him that first led you to launch into a biography of him?

I have always been interested in the connections between art and ideas—why should a particular philosophy or a religion make somebody decide that, say, wallpaper or furniture ought to look a certain way? You find those connections in all sorts of places—with the Shakers, in the work of William Morris and in the writings of Ruskin. Gradually I became aware of Pugin as somebody else in that line who hadn’t been talked about so much.

I wondered at first why you spent so much time on Pugin’s early years, but it really gives the reader an incredible understanding of a difficult and often peculiar man. What was most helpful to you in characterizing the young Pugin? Also have you any idea how his mother was educated except via her brother?

Pugin was a romantic and like all romantics the experiences of his childhood were critical. He lived with his parents for the first half of his short life, and he spent the second half trying to recapture the security and love of those years.

His mother’s letters, which are at Yale and had never been used by anybody, were immensely valuable, an extremely interesting woman in her own right her personality was in many ways the key to the formation of his.

I don’t know anything about her education as a child. She may have gone to school, she was certainly taught to play the piano, but I think like many women of her time and class she was largely self-educated through her reading.

Do you think if you lived back then you would have been attracted or repelled by Pugin? You paint this strong picture of an unkempt, uncontrolled person who is also so very honest and full of integrity. He does come to life even in the maze of economic, political, and religious turmoil.

I’m glad you find he comes to life. I think what I would have felt about him would have depended on how I encountered him. If I’d been an overworked bishop, trying to balance my accounts, I would have been exasperated by him, if I’d been a young woman who caught his attention I would have been completely captivated.

I read that you worked on God’s Architect for almost fifteen years. You give a wealth of background information that shows an amazing depth of knowledge. What area or areas of his life were of most interest to you?

I was interested by all of it. If there is a blank it is the sailing, which was a great enthusiasm of Pugin all his adult life. I never got to grips with square rigging and so forth.

What I found most interesting was the way in which his life, especially his childhood, was a microcosm of an age. I think that is one reason that he touched his contemporaries so much, that he had the typical experience of his generation only on a bigger scale. I also found that his life crossed the boundaries between disciplines, historic periods and subjects—like design history and theology—that we are inclined to keep artificially apart. It makes academic life easier but it distorts history.

The revival of the English Catholic church, the Oxford movement, and the entire economic background in England at this time is extraordinarily well presented. What were some of the discoveries or items of interest you found that kept you going through this enthralling pursuit?

This was another area where artificial divisions had been created. I found that Roman Catholic historians had said relatively little-understandably perhaps-about the Oxford Movement, and historians of the Oxford Movement—less forgivably—had ignored the early Catholic revival. Reading the letters of both groups, which was one of the most revealing parts of the research, I realized that they were all in contact with one another and indeed the two movements were completely intertwined for a decade or more. In the end I had to coin a name, Romantic Catholics, for the men and women who believed what Pugin did about England and its Catholic heritage. Their moment, though not long, was significant, yet it had been almost entirely written out of history.

Of all of Pugin’s buildings and projects which ones do you find the most influential and which for you personally are the most aesthetically pleasing?

Pugin’s own house, the Grange, at Ramsgate in Kent, was hugely influential. It really reinvented the family house for the nineteenth century and its legacy is with us still. Otherwise Pugin’s influence came largely through his books and their illustrations which were much better known than most of the buildings.

My own favorite is the Rolle Chantry at Bicton in Devon. It is a tiny building, a perfect miniature in which Pugin got every detail right. The little chapel is set amid the ruins of a medieval church and the tomb inside is beautifully carved in white marble. When the colored sunlight falls on it through Pugin’s stained glass it sums up for me everything that he wanted to achieve.

There are a great many other fascinating people surrounding the life of Pugin, some who are also not very well known. Have you found someone else in this period or milieu you would like to hone in on?

No one person, but the antiquaries like John Britton and Edward Willson who helped to form Pugin’s own vision and whose researches paved the way for him interest me a great deal. They were often eccentric, they collected all sorts of bizarre objects in an effort to try and understand the past, but they were pioneers of almost everything we mean by history today—archaeology, architectural history, oral history, social history. I’m writing about some of them.