Western Mountain Scene by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902); Centennial by Ilya Bolotowsky (1907-1981), 1949.

The New York gallery D. Wigmore Fine Art has a special talent for discovering affinities and relationships between works of art from disparate eras and in different styles, and the gallery’s current exhibition—The Changing West: 1865 to 1965—is another potent manifestation of that ability. The show includes thirty works of art inspired by the American West, mostly landscapes, and demonstrates how, for example, a geometric abstraction from 1949 can commune and communicate with a Hudson River school mountainscape painted nearly a century before.

Indian Encampment by Ralph Blakelock (1847-1919).

For its compact size, the exhibition offers a surprisingly rich survey of genres and artistic perspectives. Some of the oldest works in the show, by Albert Bierstadt and Worthington Whittredge, convey the sense of majesty and mystery the first artists to venture from the East must have felt. By contrast, Indian Encampment by the tonalist Ralph Albert Blakelock—who traveled into the West on his own and spent time among Native communities—seems almost intimate in comparison.

Installation view of The Changing West: 1865-1965

By the early decades of the twentieth century, the Western landscape as depicted by John Sloan, Ernest Lawson, John Marin and others appears gentler and more accessible, if still rugged and desolate. Fixed human habitation, as rendered by William Gropper and Henry Varnum Poor, is dwarfed by the mountains and canyons but seems peaceful if somewhat fragile. It’s difficult to know what to make of Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s mesmerizing 1941 gouache Virginia City, Nevada and its strange, near ground-level point of view: is the town rising out of the desert, or is the land about to buckle and swallow the buildings up?

Virginia City, Nevada by Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889-1953), 1941.

Under the gaze of modernists in the middle decades of the century, the art of the West took on a fresh vigor, the land stripped of myth but not of majesty and mystery. Raymond Jonson’s Casein Tempera No. 5 is a magnificent abstract depiction of a lightning storm, while Ilya Bolotowsky’s abstract Centennial—named for a town in Wyoming, and painted in 1949 while the Russian-born artist was teaching at the state’s university—is every bit as grand and imposing a snow-capped peak as Bierstadt’s.

Casein Tempera No. 5 by Raymond Jonson (1891-1982), 1938.

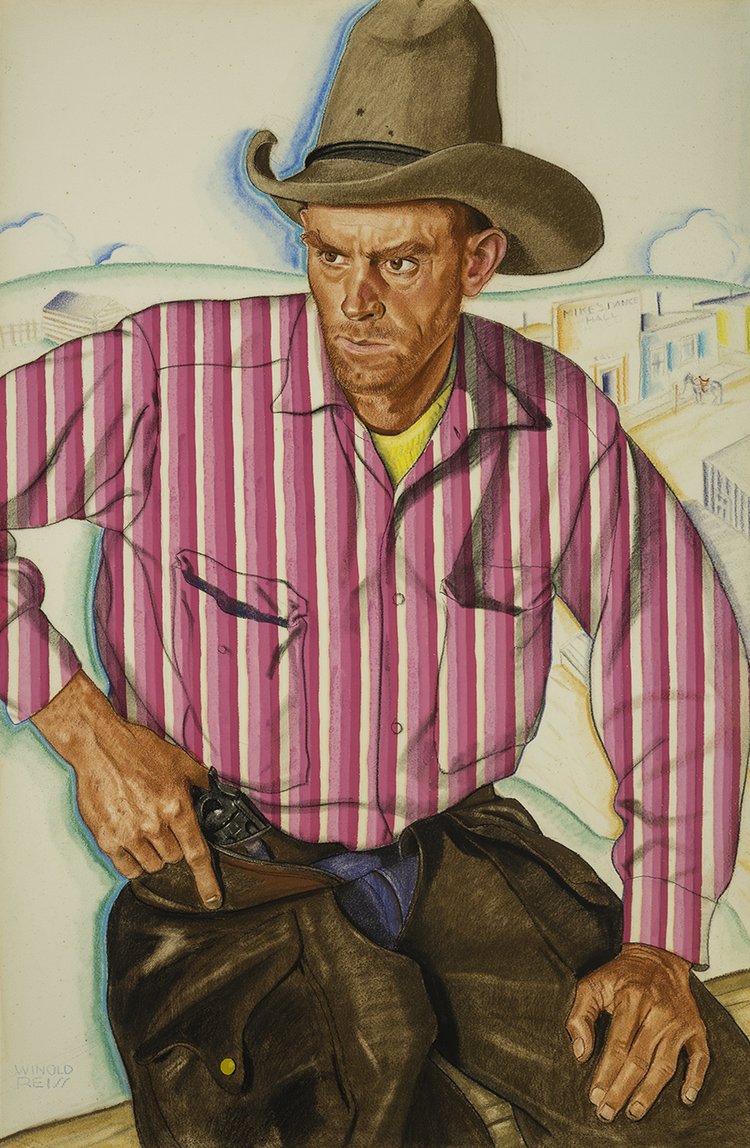

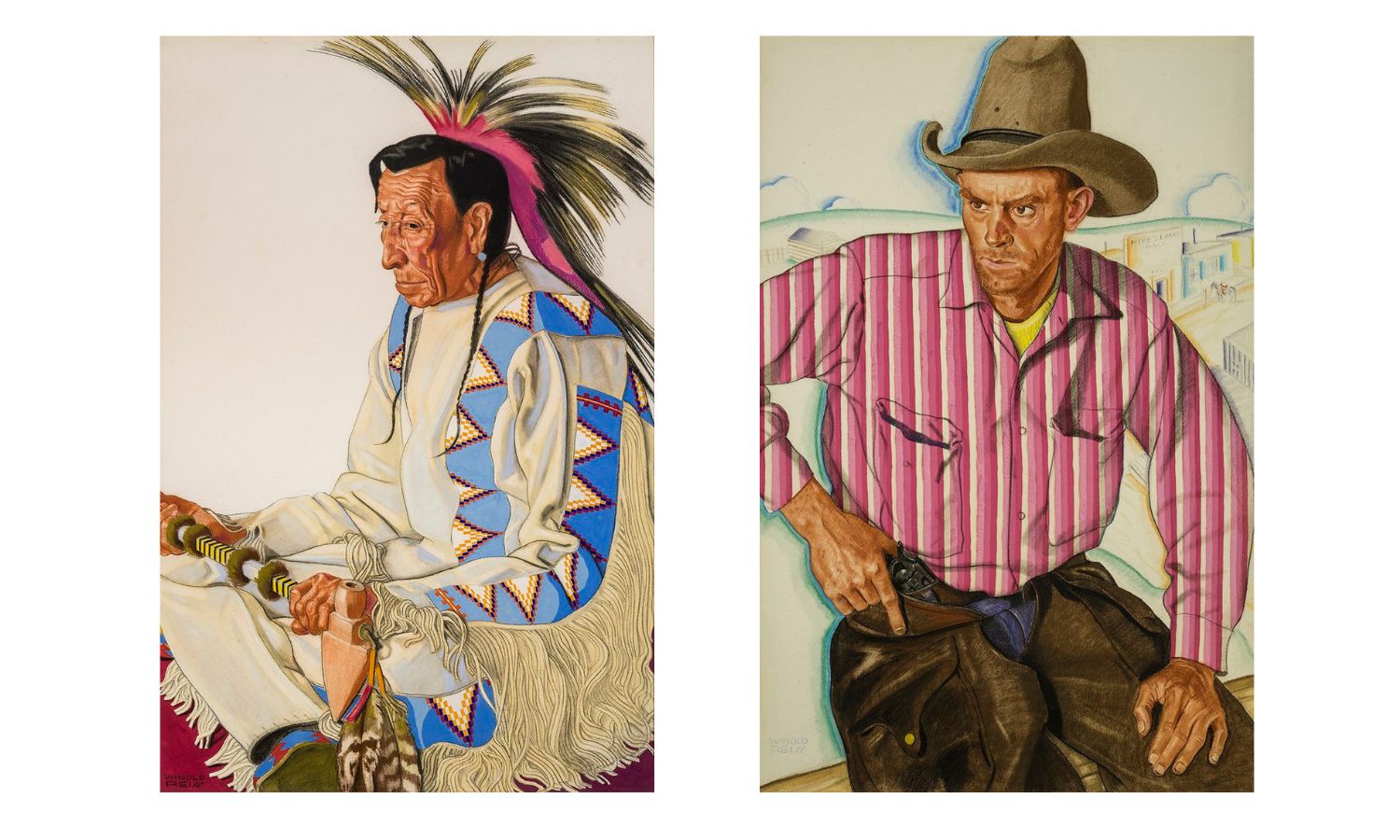

There are only two portraits in the exhibition, and they are special—as are most portraits by Winold Reiss, the German-born artist and designer who was the subject of an acclaimed recent exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. Like most German boys of his generation, Reiss had been fascinated by the frontier adventure stories of novelist Karl May. After emigrating to the US in 1913, Reiss took his first trip of many to the American West in 1920 and made friendships that lasted his life, particularly among the Blackfeet of Montana. The show at Wigmore includes a c. 1936 portrait of a Native elder named Spider Bonnet and a c. 1931 portrait of a gunslinger known as “Montana Red,” who had the unlikely surname Shy. For all the menace implicit in his depiction of Shy, Reiss wrote in his journal that he saw a sort of unspoiled innocence in the man—which perhaps explains the buoyant contradiction that is the pink- and fuchsia-striped shirt he wears.

Spider Bonnet by Winold Reiss (1886-1953), c. 1936. ; “Montana Red” Shy by Winold Reiss (1886-1953), c. 1931.

The Changing West: 1865 to 1965 is on view until May 19 at D. Wigmore Fine Art, 152 West 57th Street, 3rd Floor, New York, NY • dwigmore.com