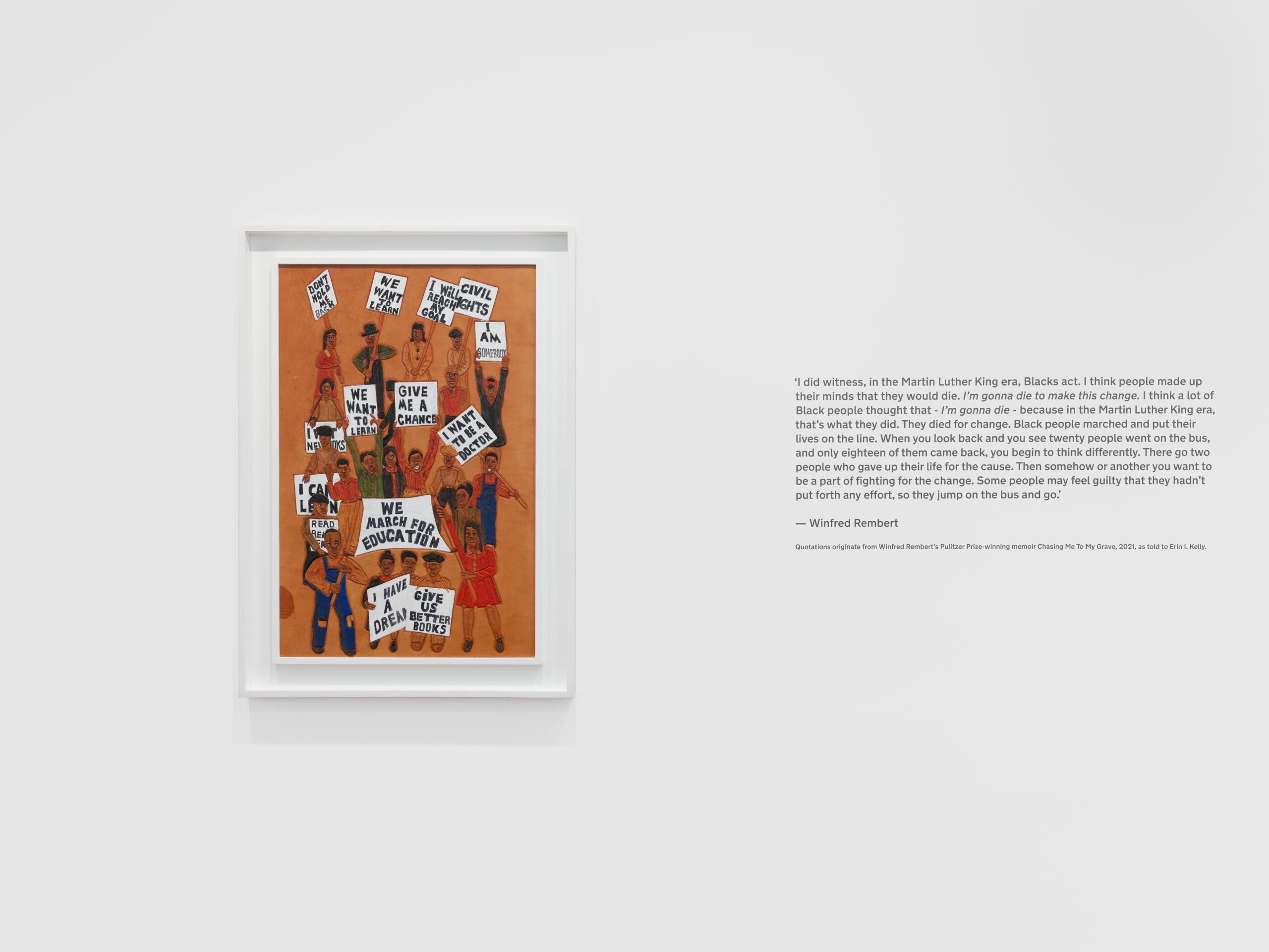

All of Me by Winfred Rembert (1945-2021), n.d. Winfred Rembert © 2023 The Estate of Winfred Rembert / ARS NY, Courtesy the estate, Fort Gansevoort, and Hauser & Wirth.

Some advice: keep your hands clasped behind your back when looking at artworks by Winfred Rembert (1945-2021). There’s a strong temptation to touch them, which of course is not allowed. Part of that urge stems from Rembert’s medium. His “paintings” are actually panels of tooled leather—that most tactile of materials—incised with figures and scenes that he dyed in vibrant colors. But the impulse to touch comes more from the stories of life in the Jim Crow South that Rembert’s artworks tell. Sometimes of joy, but more often of pain, hardship, and cruelty, these stories are so powerfully affecting that you feel an instinctive need to reach out in a simple gesture of empathy.

Installation view, ‘Winfred Rembert. All of Me,’ Hauser & Wirth 69th Street 23 February–22 April 2023© 2023 The Estate of Winfred Rembert / ARS NY, Courtesy the estate, Fort Gansevoort, and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer.

Winfred Rembert: All of Me, on view until April 22 at the Upper East Side, Manhattan outpost of the international art gallery Hauser and Wirth, offers a rare chance to engage with a large number of Rembert’s works at one time. The show, mounted in collaboration with the New York art gallery Fort Gansevoort, features 44 works by Rembert, some on loan and others for sale at prices ranging from $90,000 to $400,000. The exhibition is not to be missed.

The details of Rembert’s life have been told often—most notably in his prize-winning 2021 memoir, Chasing Me to My Grave, written with Erin I. Kelly—but bear repeating. He was born in rural Georgia and worked in the cotton fields as a boy. In the mid-1960s he took part in a civil rights demonstration that devolved into violence and was subsequently arrested. After languishing in jail uncharged for a year, he escaped, was captured and nearly lynched, then was sent to prison to serve seven years at hard labor. After his release in 1974, he married his sweetheart, Patsy Gammage, and the two eventually settled in New Haven, Connecticut. While working as a longshoreman, Rembert began using the leather-tooling and dying skills he learned in prison as a hobby, making items like billfolds. He also made a pair of leather pictures—based on images he traced from a book—which each sold for a few hundred dollars. Rembert realized he had talent, but the turning point came when Patsy encouraged him to carve images drawn from his own life experiences. He did, and at age 51 became a true artist.

Portrait of Winfred Rembert by Renan Ozturk.

Installation view, ‘Winfred Rembert. All of Me,’ Hauser & Wirth 69th Street 23 February–22 April 2023© 2023 The Estate of Winfred Rembert / ARS NY, Courtesy the estate, Fort Gansevoort, and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer.

At Hauser and Wirth, Rembert’s art is arrayed on three floors. The force of the scenic artworks on the first level is palpable. They depict the episodes that led to Rembert’s seven-year imprisonment, ranging from the attack on civil rights marchers that led to the artist’s initial arrest to the court hearing where he received a harsh prison sentence. Two of the most haunting images are titled Inside the Trunk and Wingtips. After Rembert’s capture following his jailbreak, law enforcement officers shoved him into the trunk of a car and drove him to a remote spot. The first artwork presents the harrowing moment when the trunk was opened and Rembert found himself facing an angry crowd armed with baseball bats and other clubs. The second depicts the scene a short while later: Rembert, bound and strung from a tree by his heels, gashed and bleeding from a knife wound. The title Wingtips is taken from small, poignant detail in the composition: the shoes of the man who stepped forward to put a stop to the lynching attempt. His shoes were likely the only thing about the man who saved his life that the artist, hanging upside down, could see.

Some relief from the horrors comes in a smaller space on the first floor, which contains artworks devoted to women in Rembert’s life. They include the large, lovely double portrait Patsy and Me, and the bright and busy family scene The Gammages (Patsy’s House). Such appealing tableaux of community continue in the artworks on the second floor, which include such lively compositions as Soda Shop, Jeff’s Pool Room, and The Curvey—a depiction of teenagers leaping from a railroad trestle to swim in the river below.

Jeff’s Pool Room by Winfred Rembert (1945-2021), 2003. Winfred Rembert © 2023 The Estate of Winfred Rembert / ARS NY, Courtesy the estate, Fort Gansevoort, and Hauser & Wirth.

On the uppermost floor you will find examples of the works that are considered Rembert’s crowning artistic achievement. Ten panels depict back-breaking drudgery with echoes of enslavement: in several, field workers pick cotton; others show prisoners in striped uniforms shackled together in a chain gang. Though these scenes remain implicitly brutal and degrading, Rembert nevertheless is able to make them beautiful—in mesmerizing and lyrical figural abstractions with sinuous patterns and vivid colors. There is something heroic about these artworks. They are testaments to the artist’s strength and resilience, and to the astonishing human capacity to process pain and suffering and from them, somehow, to create the sublime.

Installation view, ‘Winfred Rembert. All of Me,’ Hauser & Wirth 69th Street 23 February–22 April 2023© 2023 The Estate of Winfred Rembert / ARS NY, Courtesy the estate, Fort Gansevoort, and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer.

Winfred Rembert: All of Me • Hauser and Wirth 32 East 69th Street (at Madison) New York • Tuesdays through Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • to April 22