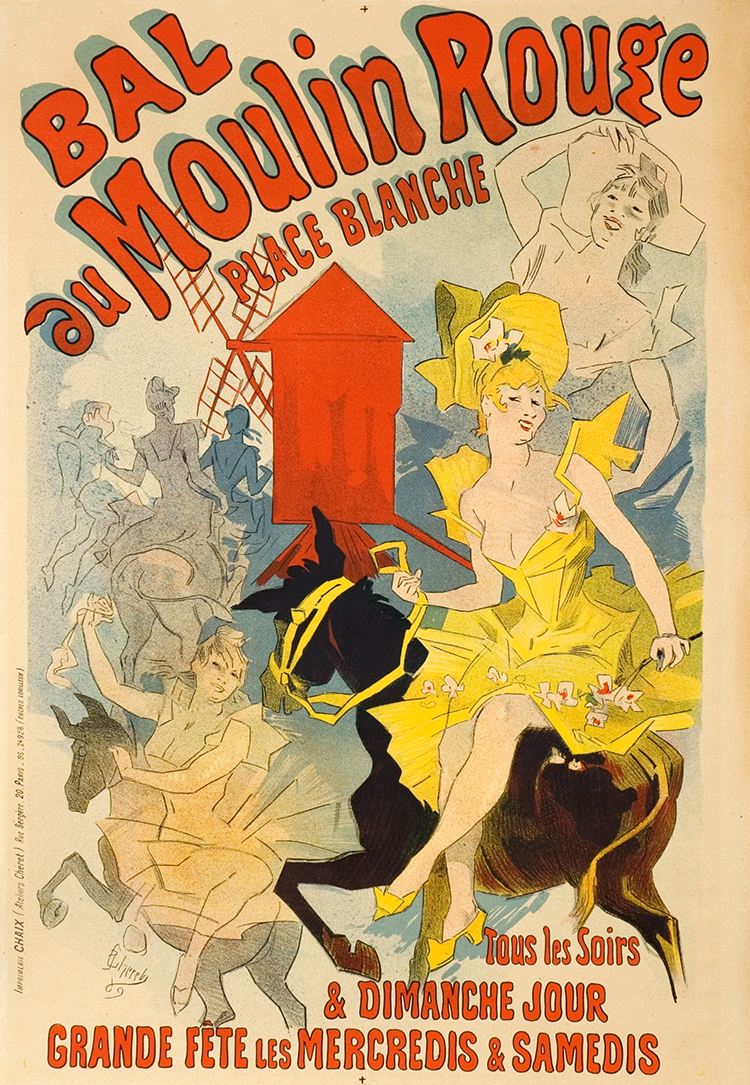

Bal au Moulin Rouge by Jules Chéret, 1889. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University; photograph by Jack Abraham.

In 1796, little-known German playwright Alois Senefelder was casting about for a way to reproduce his scripts more quickly. What he hit upon—printing from a limestone matrix smeared with ink-repelling grease, now known as lithography—would usher in a new “stone age” of sorts, and start a revolution in the production and reproduction of images, the effects of which are being felt to this day (one spinoff was photography, the discovery of a frustrated lithographer). Surveying the first century of the upstart medium is Set in Stone: Lithography in Paris, 1815–1900, on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Jersey.

Though not able to render prints that were as sharp as those produced by etching, lithography’s limestone was much more durable than metal or wood, and could be used to create an abundance of prints before the stone was ground smooth again and reused. Better yet, making lithographic prints didn’t necessitate the mastering of the chisel or needle, just of familiar drawing tools such as crayons. Artists in France were quick to embrace the medium, leading to lithography’s first inclusion at the Salon in 1817. Two of art lithography’s test drivers were Francisco Goya, who created his swirling, tenebrous Bulls of Bordeaux in the medium, and Eugène Delacroix, who provided demoniacal lithographic illustrations for the 1828 French edition of Goethe’s Faust.

By mid-century art lithography had become something of a victim of the general success of the medium. Associated with gluts of cheap, commercial reproductions, it ceded ground to etching. Further technical advances were needed before the true—and brief—golden age of lithography would shine forth. They came in the form of steam-powered presses capable of processing huge slabs of limestone and improvements in four-color printing, and resulted in the creation of the stunning posters by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Pierre Bonnard, and Jules Chéret, so indelibly associated with turn-of-the-century France. Some of those peerless posters, such as Toulouse-Lautrec’s Divan Japonais and Steinlen’s Tournée du Chat Noir, are among the more than 120 works on view at the Zimmerli.

Set in Stone: Lithography in Paris, 1815–1900 • Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ • to July 29 • zimmerlimuseum.rutgers.edu