When New-York Historical Society curators invited Kay WalkingStick to visit their art storage facility in Jersey City to consider some Hudson River school landscapes, I don’t think they did so because these works needed rescuing. They undoubtedly thought the paintings could benefit from a fresh view by a nimble artist who is both unafraid of beauty and adept at looking the past in the eye. That the artist identifies as Native American (her father was Cherokee, her mother of Scots/Irish heritage) made the current exhibition of her work alongside the kinds of mid-nineteenth-century paintings she has been looking at carefully, critically, and appreciatively for years all but inevitable.

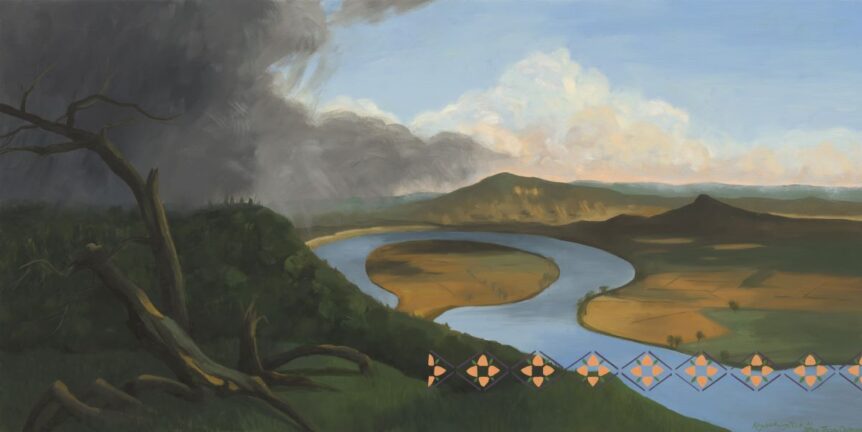

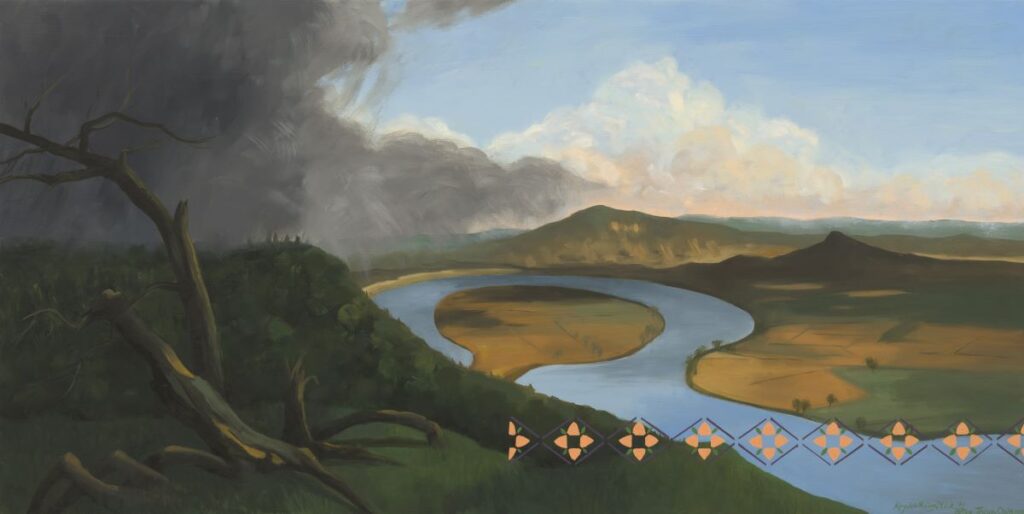

Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School manages to do several things at once, some expected, some not. In the former category it is not too surprising to find her response to a well-knownpainting not on display, Thomas Cole’s View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (Fig. 2), in a large canvas from 2020 echoing that scene and titled Thom, Where are the Pocumtucks (The Oxbow) (Fig. 1). Although her painting, like Cole’s, is notably absent of Native figures, she has inscribed their presence on it with a stenciled design from the Nipmucks, the valley’s current residents. Point made, and, yet, in its beauty her work is indeed something of an appreciation of Cole’s, even though its title is wry and its spirit less melodramatic.

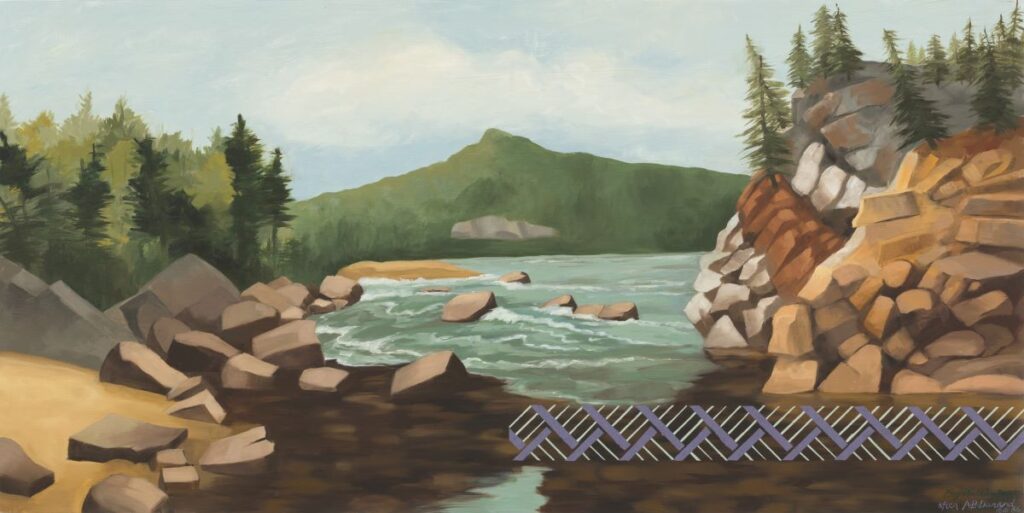

WalkingStick had done much of the same thing with Asher B. Durand’s East Branch of the Ausable River (Fig. 3), again overlaying a Native pattern appropriate to this Adirondack scene in her slyly titled Durand’s Homage to the Mohawks (Fig. 4). If Cole, Durand, and others insisted on giving us the impression that their scenes were pictorially and even historically accurate, WalkingStick’s stencils draw attention to their revisions and omissions, while also honoring sites of great beauty.

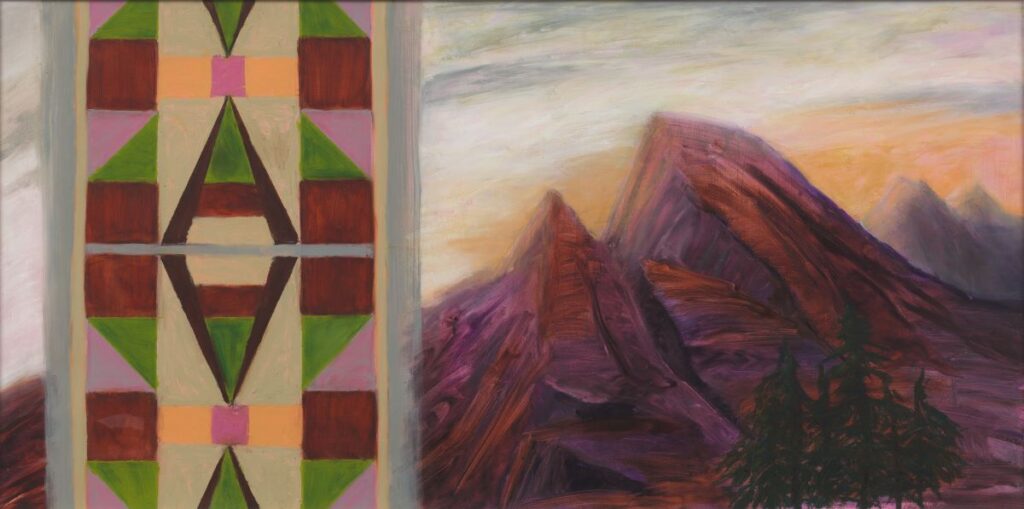

Artists like Cole and Durand are one thing, but Albert Bierstadt is quite another. No artist of the American landscape has come in for more criticism for imbuing natural scenes with jingoistic fervor than Bierstadt. WalkingStick does not so much confront his work and others like it as transcend it, painting both the Smokies—Farewell to the Smokies (Trail of Tears) (Fig. 5)—and the Rockies (Our Land Variation II) (Fig. 7), in a way that both reclaims the American sublime while joining it to the traumas of Native American history.

Kay WalkingStick has been a notable figure in the art world for decades now, and the works on view at the New-York Historical Society are only a small sample of what she has done. Since the 1980s she has often produced diptychs, sometimes pairing an abstraction with a representational image, sometimes creating mirror images of the same scene. A few of those diptychs are on view here. They should remind viewers of this artist’s capacity for looking both ways—past and present, hope and despair, Native and not. That spirit imbues this exhibition, allowing us to look beyond the carved and gilded frames of our mid-nineteenth-century artists, with a new perspective on the perennial question, what is American in American art?

Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School is on view at the New-York Historical Society through April 14.