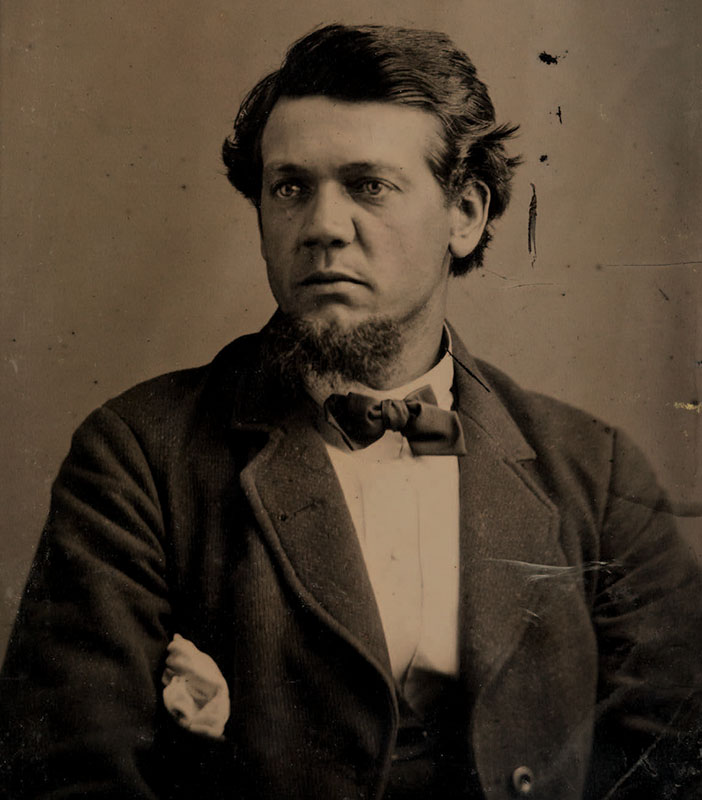

On July 16, 1870, Edward Lange stepped off the SS Frankfurt onto the docks of New York Harbor (Fig. 1).1 We can only guess at the mix of emotions running through the twenty-four-year-old artist’s mind. The world he was about to enter was an uncertain one, but surely more stable than the one he had left behind. Lange came from the independent state of Hesse-Darmstadt in present-day southern Germany. The day he arrived in New York, had he glanced at a newspaper, he would have seen headlines that likely felt inevitable for some time, such as the one on the front page of The Sun: “France Declares War. Prussia Accepts the Challenge.” Thoughts of home must have weighed heavily on Lange’s mind as he made his way through the crowded streets of New York for the first time.

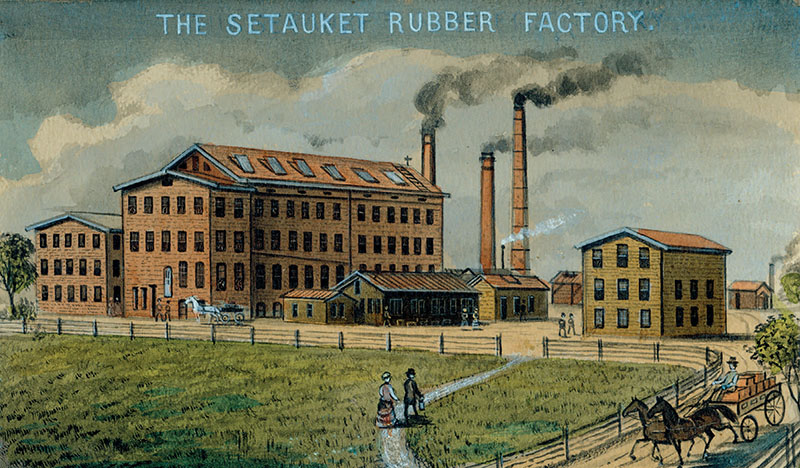

Lange settled near Elwood, New York, on a 148- acre plot of land that his father, Gustav Georg Lange (1812–1873), had purchased in 1856, presumably as an overseas investment. Ownership of the land passed to Edward Lange in 1872 and he lived there until 1889.2 The Long Island that he came to know was undergoing rapid change, as rural landscapes and an agricultural economy gave way to urban sprawl and new industries. Factories opened in droves along the North Shore. The Long Island Railroad expanded, better connecting islanders to New York City’s metropolitan hub. Towns and villages opened recreational clubs that quickly became tourist destinations, welcoming the thousands of visitors from the city and Connecticut who arrived on regularly scheduled steamers. In the midst of this bustling world, Lange became known for his watercolor renderings of estates, railroad depots, commercial businesses, and waterfronts in fastidious detail.

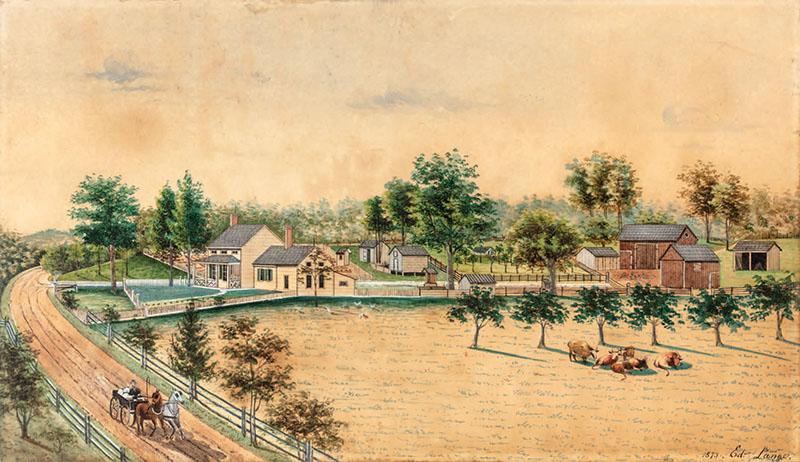

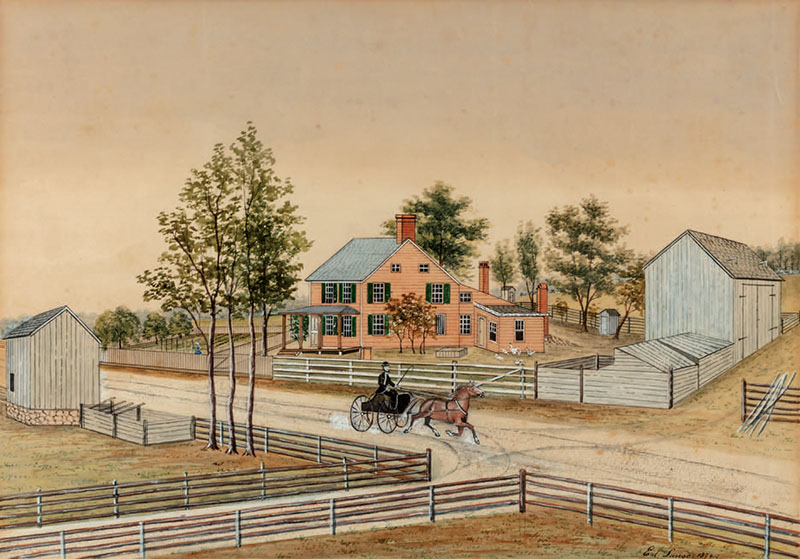

During the 1870s, Lange’s artistic style resembled that of other immigrant itinerant artists active around the same time. In both subject and composition, his work echoes the house portraits and almshouse pictures of artists like Ferdinand A. Brader (1833–1901), Charles C. Hofmann (c. 1820–1882), and Fritz Vogt (1842– 1900). Lange’s first artworks were commissions from individual property owners, each of whom lived within a few miles of him in the Town of Huntington. The Residence of Zebulon Buffett, Jericho Road, Long Island (Fig. 3), John Frederick Nevius Homestead (Fig. 4), and Long Island Farmstead with Red House (Fig. 5) are three examples of his early commissions, all painted in watercolor with graphite under-drawings and highlights. Lange’s skill as a draftsman is clear even in these early works. The detail with which he delineated architectural elements and fencing around property lines suggests a practiced eye for perspective.

There is no evidence that Lange trained in academic fine art before he immigrated. Rather, his early artistic efforts in the United States were likely born of the skills he learned watching more experienced artists in his family. Lange’s father owned a printshop in Darmstadt and worked as an engraver and book publisher. At times, Gustav Georg employed his two brothers—Ludwig Lange (1808–1868) and Julius Lange (1817–1878)—who were trained in architectural draftsmanship and landscape painting. The brothers collaborated on their best-known productions during Edward’s formative years and likely mentored the young boy.3

Lange was also likely influenced by mid-nineteenth-century American lithographs and the style of the engraved illustrations in county atlases.4 Between 1864 and 1890, American cartographers produced 123 atlases that mapped 114 of the 150 counties in New York, New England, and New Jersey.5 The popularity of these subscription-based atlases and of illustrated regional history books was boosted in the years surrounding the centenary of the United States, heightened by celebrations of local American life. The same sensibility helped focus Lange’s own work. It seems intuitive that he might have participated in the production of such publications, but there is little evidence that his sketches were ever adapted for print publication by the hand of an engraver.6

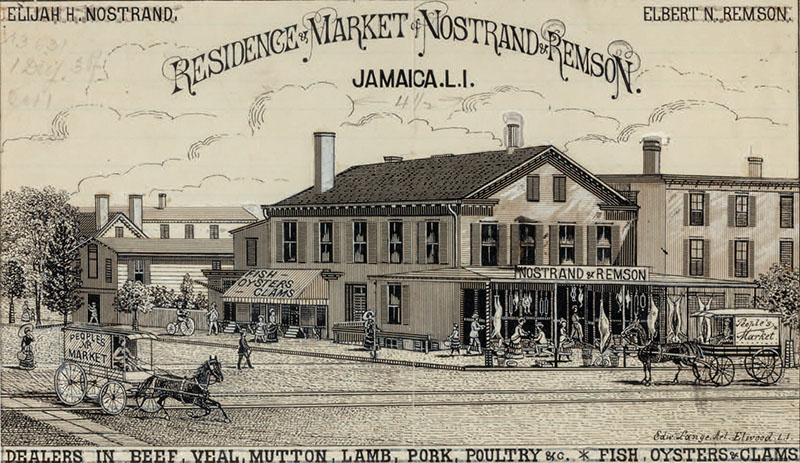

During the late 1870s, however, some of Lange’s work did appear in print, via the process called photoengraving. This method reproduces a work of art on a printing plate exactly, instead of the work serving simply as a reference for an engraver copying the scene. It was a popular technique for printing trade cards, letterheads, and other paper ephemera. Residence & Market of Nostrand & Remson. Jamaica. L.I. is one example of the work Lange created for that purpose (Fig. 6). He made this commercial advertisement depicting a street scene in Jamaica, New York, with collaged paper overpainted with India ink and white gouache highlights. A close look shows the dozens of tiny pieces of printed paper that demarcate unique architectural elements of the buildings and make up the surrounding scenery.

Lange’s adoption of mixed mediums was driven by the demands of photoengraving processes. Although photoengraving had been in use as early as the 1820s, it was not widely adopted for illustrating books, periodicals, and newspapers until the late nineteenth century. For original artworks to be successfully etched onto a plate with the photoengraving process, they needed to have high contrast and definition. Printing companies of the late 1870s distributed notices reminding artists that “drawings to be copied should be made in line, with black ink (India) on smooth white paper.”7 Lange likely found that his method of collaging and highlighting preprinted pieces of paper resulted in photoengraving of the highest quality.

Lange’s interest in commercial art and photoengraving offered a sharp departure from his earlier house portrait work, likely motivated by a desire to seek out more profitable art markets. To his disadvantage, the greatest concentration of photoengraving companies, as well as potential businesses who might enlist his services, were not located in Suffolk County, but in New York and Brooklyn. His desire to seek these types of commissions likely motivated him to move his family to New York in November of 1878. Unfortunately, it was a short-lived experiment. The Langes fell seriously ill with diphtheria and scarlet fever over the winter. After the death of their youngest daughter, the family moved back to Long Island, having stayed in the city just three months.8 Whether the result of his brief exposure to new exhibitions of landscape art in the city or influenced by other factors, Lange’s watercolor and gouache art changed dramatically after his return to Long Island.

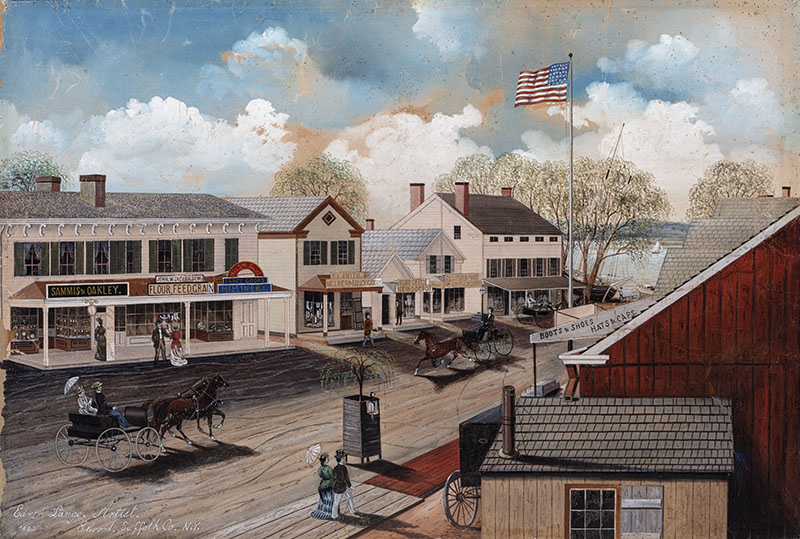

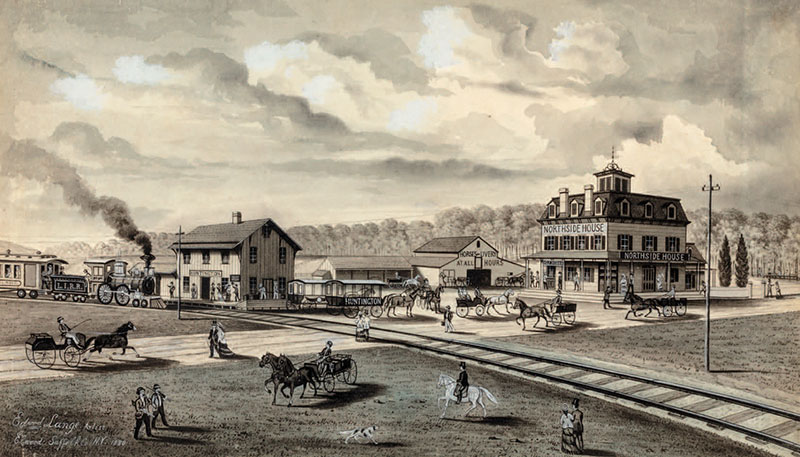

More of Lange’s work survives from 1880 and 1881 than from any other years, in large part because he imbued these artworks with a richness previously absent in his productions. His views of Lower Main Street, Northport (Fig. 2) and Thimble Factory, Northport, N.Y. (Fig. 7) were both painted in 1880 and feature skies that echo one another in composition and pigment selection. The clouds in each sky bring a sense of drama and life to these scenes, reminiscent of the atmosphere of the Hudson River school landscapes of the early and mid-nineteenth century. Painted en grisaille, Lange’s Huntington Depot evokes the same kind of energy with shadowy clouds cutting diagonally across the upper third of the paper—pairing neatly with the movement suggested by the steam engine’s smoke as the train arrives at the station (Fig. 9).

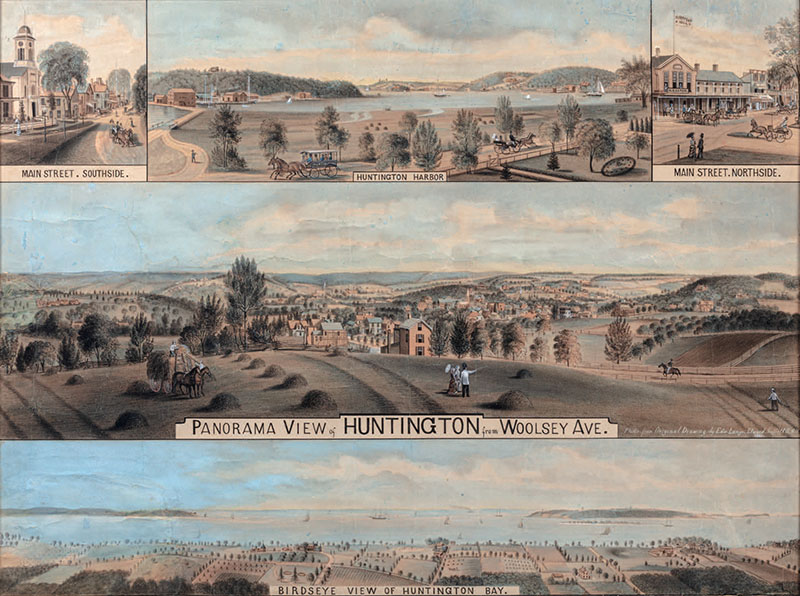

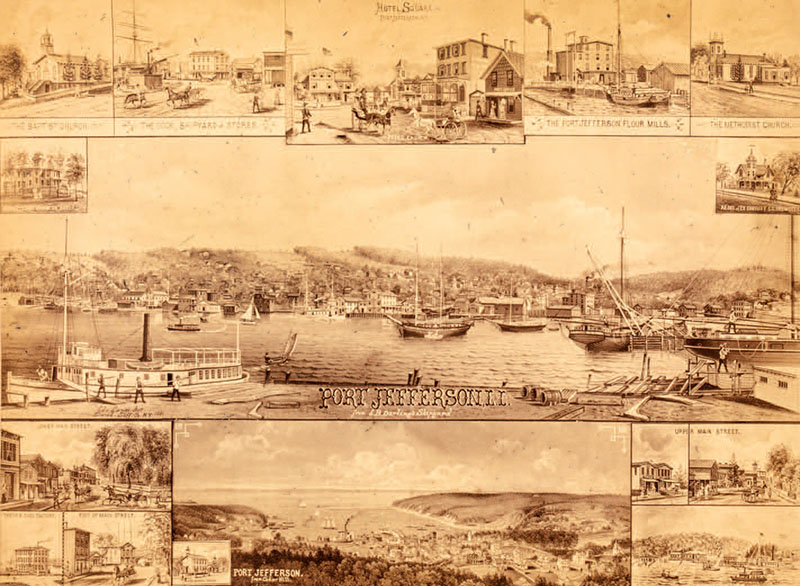

Though Lange renewed his efforts to produce original paintings, he remained attached to the idea of using photography to sell reproduced versions of his work. In 1881 he advertised in the Long-Islander seeking subscriptions “to draw and copy by photograph three different views of Huntington. . . the three to be mounted on one board.”9 Interestingly, Lange painted the composite landscape—known today as Panorama View of Huntington from Woolsey Avenue (Fig. 8)—in color, despite only having the capability to photograph the artwork in the characteristic sepia tones of albumen photographic prints of the time (Fig. 11). Lange’s endeavor met with such success that he continued to produce and photograph composite collections of his original artworks, increasingly with an eye toward the growing tourist market on Long Island. Lange traveled widely, recording small scenes of notable buildings and landmarks in watercolor and gouache (Fig. 10). He then pinned collections of these scenes together and photographed them as composite artworks meant to be reproduced and sold as prints (Fig. 12).10 Local newspapers celebrated Lange’s photocopied composite prints, asserting that “there could be no better advertisement for these beautiful villages and their surroundings.”11

Lange found success on Long Island because he was willing to adapt his style and technique to make art that met the demands of the popular market. However, the need to constantly search for new markets grew tiresome. In 1889 he moved west with his family to Olympia, Washington. The boom of new business there offered richer opportunities and more stability. Lange continued working as an artist and photographer until his death in 1912.12

Although Lange only spent nineteen years on Long Island—just half of his artistic career in America—his artwork continued to have a compelling impact on local communities. In 1947 the Huntington Historical Society organized the first major retrospective of his work, thirty-five years after his death. Some visitors to the exhibition may very well have crossed paths with the artist in their youth, but Lange himself might not have recognized the Long Island where those same people now lived. His evocatively populated farmsteads, harbor fronts, and main streets belonged to a seemingly distant past, one untouched by the maze of parkways and suburban developments that had come to define the region by the mid-twentieth century.

Recognizing the importance of the artist’s corpus to local history and preservation efforts, Dean F. Failey—curator of Preservation Long Island (then known as the Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities)—embarked on a major project in the 1970s to publish Lange’s known works and delve into the artist’s surprisingly elusive career.13 Today, Preservation Long Island continues to examine his artistic influences, process, and productions with The Art of Edward Lange Project. In the past year, this initiative has produced a new website that hosts a database of more than one hundred Long Island artworks by the artist, fully illustrated with high-resolution images. Collecting Lange’s work in a single virtual space for the first time lays the foundation for pursuing more critical questions about his oeuvre—encouraging further discussion about his changing motivations, adaptation to new technology, and what the artist chose not to include in his landscapes. New inroads of inquiry into Lange’s life and his work will appear in Preservation Long Island’s forthcoming publication on the artist, expected to be released in 2024. This fall, we invite you to visit Land by Hand: Edward Lange’s Long Island, 1870–1889 at the Long Island Museum, an exhibition curated in partnership with Preservation Long Island.

Land by Hand: Edward Lange’s Long Island, 1870–1889 will be on view at the Long Island Museum in Stony Brook, New York, from September 22 to December 30. A smaller edition of the show is on view at Preservation Long Island in Cold Spring Harbor until August 28. The Art of Edward Lange Project, funded by the Gerry Charitable Trust, is an ongoing effort. Readers who know the whereabouts of any of Lange’s artworks, or would like to engage further with the project, are asked to contact the authors via preservationlongisland.org.

1 “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820–1957,” Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives, Washington, DC, microfilm publication M237, 1820–1897, line 46, list number 683, accessed via ancestry.com. 2 For the purchase of the land by Gustav Georg Lange and its passing to his son Edward, see deed between William C. and Mathilda Lange and Gustavus George Lange, July 26, 1856, Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Archives, Liber 90, pp. 113–117; indenture between Gustav Georg Lange and Edward Lange, May 18, 1870, ibid., Liber 189, pp. 87–91.3 The brothers’ work is chronicled in Ludwig Lange et al., Originalansichten der historisch merkwürdigsten Städte in Deutschland, ihrer Dome, Kirchen und sonstigen Baudenkmale (Darmstadt, Germany: Gustav Georg Lange, 1832–1867).4 L. H. Everts and F. W. Beers and Company produced some of the best-known county atlases during the last decades of the nineteenth century. For more on the design tradition of itinerant immigrant artists and their relation to county atlases, see Andrew Richmond, “The Views of Ferdinand A. Brader: An Historical Perspective,” in The Legacy of Ferdinand Brader, ed. Kathleen Wieschaus-Voss (Canton, OH: Center for the Study of Art in Rural America, 2014), pp. 1–13; and Don Yoder, “The Farmstead Views of the County Atlas: Closest Parallel to the Brader Drawings,” ibid., pp. 15–23. 5 Douglas Kendall, “How ’Twas Done: The Making of County Atlas Illustrations in Nineteenth-Century America,” in Drawn Home: Fritz Vogt’s Rural America (Cooperstown, NY: Fenimore Art Museum, 2002), p. 56. 6 The illustrations reproduced in History of Suffolk County, New York, with Illustrations, Portraits, and Sketches of Prominent Families and Individuals (New York: W.W. Munsell, 1882) have been previously attributed to Lange, but there is no evidence that this was the case. See Dean F. Failey and Zachary N. Studenroth, Edward Lange’s Long Island (Setauket, NY: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1979), p. 13. 7 American Photo-Lithographic Company, “(Osborne’s Process) Photo-Relief Plates,” Pettengill’s Newspaper Directory and Advertisers’ Hand-book (New York: S.M. Pettengill, 1878), p. 358.8 “Dix Hills,” South Side Signal (Babylon, NY), November 2, 1878, p. 2, and ibid., February 1, 1879, p. 3. 9 “Village Notes,” Long-Islander (Huntington, NY), August 26, 1881, p. 2. 10 See James M. Reilly, The Albumen and Salted Paper Book: The History and Practice of Photographic Printing, 1840–1895 (Rochester, NY: Light Impressions Corporation, 1980). 11 “E. Lange, the well known artist…,” Long-Islander, June 17, 1881, p. 2. 12 A letter Lange sent back to a friend on Long Island in 1893 makes it clear that he did not miss New York; see Edward Lange to Carll S. Burr, February 6, 1893, Preservation Long Island, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. 13 Failey and Studenroth, Edward Lange’s Long Island.

LAUREN BRINCAT is the curator at Preservation Long Island. PETER FEDORYK is the Art of Edward Lange Curatorial Fellow at Preservation Long Island and editor of Thoughts and Occurrences: The Journal of Thomas Cole (2022).