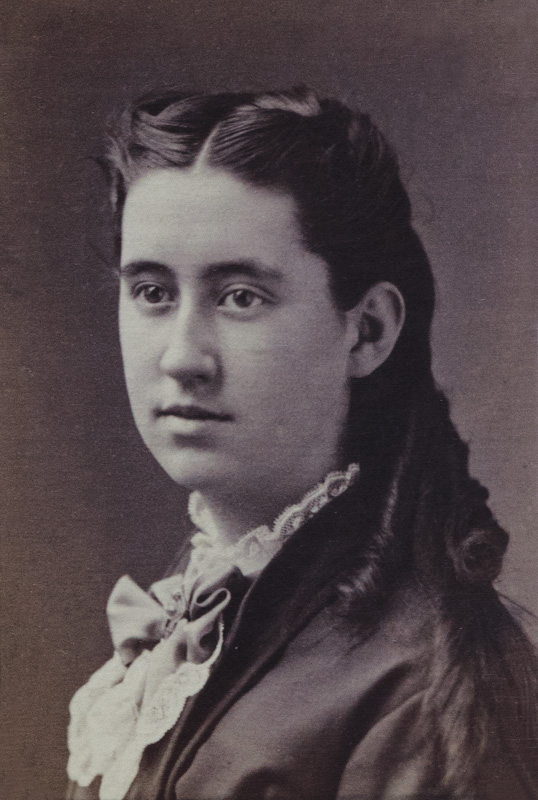

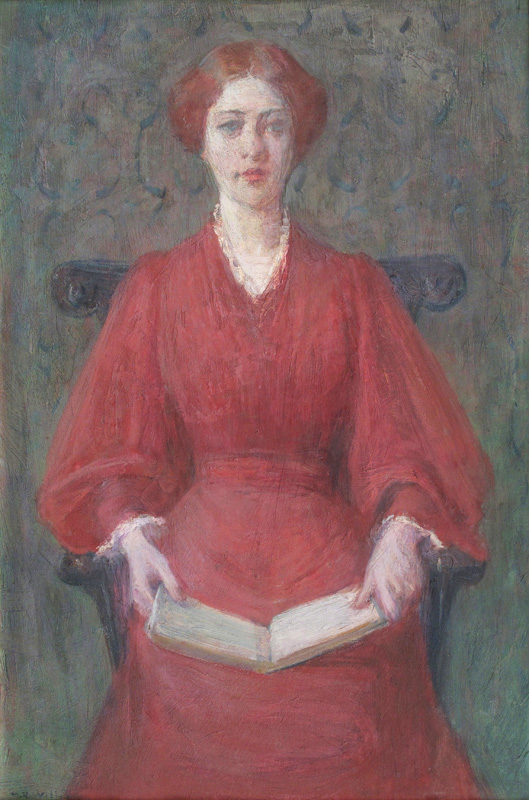

The painter Mary Rogers Williams, a baker’s daughter from Hartford, Connecticut, may be the only nineteenth-century woman artist whose thoughts and feelings are almost fully known. As she biked and hiked from the Arctic Circle to Naples, exhibited her work from Paris to Indianapolis, and taught at Smith College for nearly two decades, she wrote thousands of pages about her travels and work to friends and family. Eve M. Kahn’s new book, Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857–1907, is based on a trove of Williams’s correspondence and artwork that surfaced in 2012.

This excerpt from Kahn’s chapter about Williams’s 1891 adventures sheds light on a budding female cosmopolitan’s view of a celebrity, and her feisty reactions to the hassles of defying her era’s expectations on the road. That year, she and a friend spent their first summer overseas and brazenly asked to visit Whistler’s home in London. Williams enthusiastically detailed the visit in her journal and letters home to her unmarried sisters in Hartford.

During Williams’s 1891 whirlwind through England, France, and Germany, her daily letters exulted over rough sea crossings, mocked royalty and uncultured tourists, admired men in uniform, reported on sketching spots and passersby’s clothing, and longed to have her unworldly sisters Abby, Lucy, and Laura with her. Williams sometimes dreamed that she was home, even while feeling ever more European.

She crossed the Atlantic with a Smith art school graduate, Minna Talcott (1859–1931). Many passengers, including Talcott, were debilitated with nausea and retreated to their staterooms: “Such lots of men have been sick,” Williams wrote home. She stayed on deck to watch porpoises and birds pass by: “I like to get on the top of a big swell and go plunging down and up.”

Soon after they reached English shores, services in Chester’s cathedral brought Williams to tears (she was accustomed to staid Yankee Episcopalian practices): “I had hard work not to make a spectacle of myself. . . . I shall bust with feelings if I see much more.” She toured the church grounds with “the jolliest and most elegant old verger” pointing out a “hoak” cabinet full of vases and embroideries. Williams never ceased to be amused by provincial Britons’ misplaced h’s—she described her English breakfasts as “am and heggs.” In London, the streets looked “brighter and cleaner” than she had imagined they would, and in museums, she quickly saw enough “to make me almost wild. . . . My mind is just full of the lovely Botticelli’s and Fra Lippo Lippi’s, Velazquez’s and Rembrandts. . . . I think this is all more than I deserve.” In South Kensington, at what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum, Williams saw “more gorgeous, lovely, and priceless things than I can ever remember half of!” But she abhorred artists “thick as flies” in museum galleries, producing “atrocious copies” of masterworks: “You cannot imagine the horrors that were being made in front of our idols.”

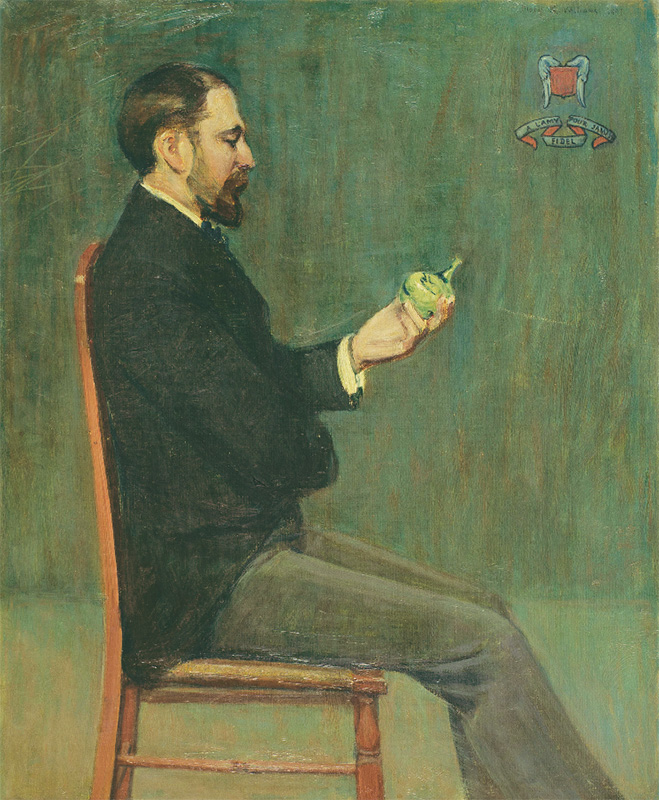

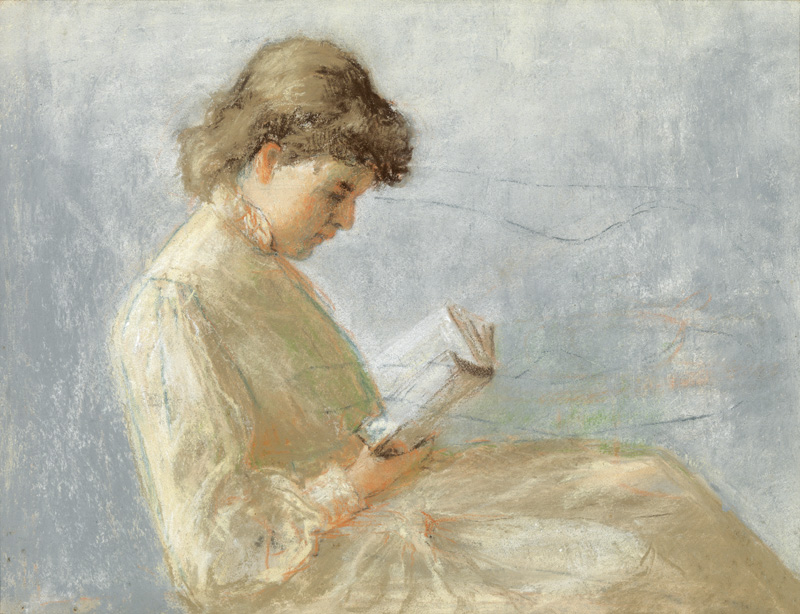

She and Talcott watched Kaiser Wilhelm, chaperoned by bewigged footmen, cross London while “visiting his granny,” Queen Victoria: “The Emperor looked a little uneasy and did not bow as gracefully as he ought, but the Empress was charmingly beautiful.” The London celebrity who charmed her most, however, was “the great Whistler.” She sent him a note asking for an audience, and he immediately agreed. She arrived saucer-eyed and “nearly scared stiff” at 21 Cheyne Walk. (The scandal-plagued master, she could not have known, was preparing to leave London and had broken off contact with his patron Frederick Leyland, who owned Whistler’s Peacock Room—a jewel-box that Charles Lang Freer eventually acquired.) Whistler was “kind and jolly,” although he did complain about “a vile portrait” that had gone on exhibit—meaning William Merritt Chase’s depiction of Whistler from 1885 as an effete, elongated dandy (Fig. 9). Whistler brought out his latest pastel portraits for Williams and Talcott, laughed at their compliments “in the most bewitching way,” and toured them through his studio and garden, “such an entrancing place.” He suggested that his guests also stop by the Peacock Room at 49 Princes Gate, but without mentioning him; the owners “do not like me,” he said cagily.

Talcott and Williams, chaperoned by Leyland’s footmen, then wandered through the “most gorgeous” Peacock Room and roomfuls of tapestries and Pre-Raphaelite and Old Master paintings. Williams longed to “stay there a week.” But she was largely disappointed by her trip to the Society of Portrait Painters’ show at the New Gallery on Regent Street; she found “Whistler’s portrait of his mother and a girl in white” comparable to “an oasis in the desert.” She concluded that Whistler was “a rare dear, and I adore him.” (She could not have foreseen that during her 1898–1899 sabbatical, when she enrolled in Whistler’s academy in Paris, she would come to resent his pomposity and self-absorption and consider him a “little tin god on wheels.”)

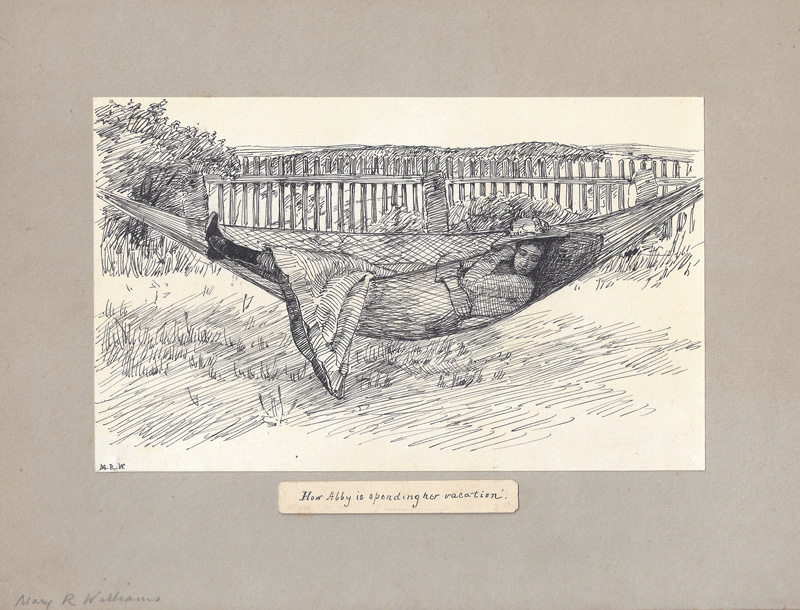

The rest of Williams’s 1891 weeks in England went by in a blur of hotels, churches, castles, third-class train rides, museums, and after-dinner hours writing home “by the brilliant light of two tallow dips.” The baker’s daughter developed ever fiercer opinions. St. Helen’s Bishopsgate, begun in the 1200s, seemed “a queer little affair with a very strong odor of sanctity.” At St. Paul’s, “a bad echo spoiled somewhat the effect of the music.” Dulwich Picture Gallery had “no fine examples of the early Italians.” She was annoyed by security checks on people’s handbags at the entrance to the Tower of London: “This performance has been in vogue since the dynamite scare about four years ago,” she wrote (referring to threats from Irish independence fighters). She meanwhile longed for “a Ouija board to find out” how her sisters were spending their vacations—Abby and Lucy were schoolteachers—at the family’s farm in Portland, Connecticut. Williams jokingly warned that she might not come home, given her urge to dress up in “fetching” men’s uniforms seen on the streets: “I am just gone on the military any way. If I don’t turn up on time in September you may know that I have joined a regiment.”

In late July, she and Talcott crossed the English Channel, “calm as a stone saint,” to the Continent: “At last I feel like a stranger and wanderer.” Smells assaulted her: “the gutters are used as sewers.” Annoyances in Catholic churches included “glitter and artificial flowers,” parishioners seeking offerings in “a continual jingle of sous” and pew space wasted on “impolite Americans who talked and consulted their Baedekers.” She nonetheless sat through services at several churches each Sunday, caught up in “clouds of incense” rising over “priests in gorgeous gold embroidery.” She was amused by “a most ambitious artificial waterfall” in the Bois de Boulogne, and a railroad station’s regal private waiting room for President Marie François Sadi Carnot (who would be assassinated three years later by an Italian anarchist): “He had a crimson carpet spread down for him. . . . This is a republic, Aha!”

At the Louvre, she wrote, “I had a pleasant time with my early Italians. . . . I saw some most beautiful frescoes by Botticelli, the actual piece of wall brought from Italy. O! They are so beautiful!” Her other favorites included Millet’s The Gleaners and a Constant Troyon tableau of cattle at dawn, which perhaps reminded her of Connecticut pastures. She was served hotel soup that “tasted as if it would be good to mount photographs with” and pined for Connecticut’s “succotash, corncakes, summer squash, and all the delicacies of the season.” Letters from home, which a bank was supposed to forward, were stuck in limbo: “It is dreadful to be so long without them.” When the sisters’ misdirected envelopes finally arrived, she wrote, “I would like to punch the head of the Cheque Bank.”

Talcott, by contrast, was left anxious amid all the unfamiliar experiences and “lost all confidence in herself.” When a man on a train identified passing birds for Williams, Talcott threatened to “send for my sisters if I flirt with any more Frenchmen. . . . I am a great trial to Miss T. because I sing before breakfast.” Talcott did muster the French language skills, however, to dismiss porters offering services, telling them “we knew what we wanted and they couldgit.’” Although the sisters worried that beggars had tugged at Williams’s heartstrings, “Miss T. keeps a sharp eye on me and scoots me by the mendicants.”

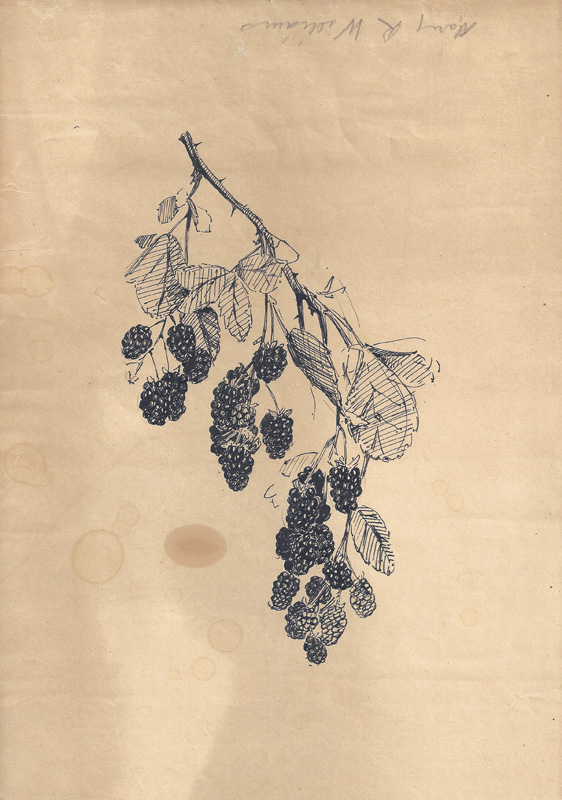

In the French countryside, Williams carried her folding stool deep into “wild rocky places” to draw scenery. Crowds gathered as she paid villagers a few sous to pose. She felt conflicted about admiring the quaint buildings amid dire poverty: “It made my heart ache to see the babies toddling about on those steep stones.” While a “dear dirty little model” was posing for Williams, “one of her comrades appeared in quite spotless condition and hair most agonizingly dressed in would-be curls, evidently wishing to serve as a model also.” An elderly beggar stopped by, too, and “struck a most picturesque attitude near me.” One young fan “kicked over my water in his attempt to get quite near. How scared he looked! He ran to the pump like a little spider to make good the loss.” Another admirer “held my umbrella over me” when rain fell.

Along the northern French coast, Williams tried to capture sailboats stranded at low tide: “I sat down on the rocks and began a sketch, but had done very little when the tide began to come in and soon my drooping boats were erect and bobbing up and down merrily.” She saw three rainbows in one afternoon, and she had “a most novel experience” of walking barefoot “a mile and a half across the wet sands. . . . It was great fun in spite of the broken shells. . . . The hardest walking was where the sand had been furrowed by the waves and it was like corduroy.” The future writer of thousands of pages approached a loss for words: “queer, interesting, charming, wonderful, très-joli, très-gentil, très-merveilleux and fifty more adjectives are not enough!” She wrote home about “women washing clothes in the streams, and doing all sorts of work in the fields,” as well as cute babies in train cars, including “a perfect beauty that I could not take my eyes off.” While peasants and tourists danced around a bandstand, illuminated by candles hanging from wires, “I laughed till I was weary.”

Still, travel had its downsides. Fleas crept into her clothes, and she used cologne to mask smells in trains, slums, and hotels. French passersby, unaccustomed to intrepid foreign women on the road, stared at her: “I feel sometimes like passing around my hat and think I might get enough for our expenses.” Home was in her dreams and on her mind. The Rance River “winds about like the Connecticut and is not a bit more beautiful, rather different in detail however with its castles fishing boats and quaint houses.” Her sisters praised her descriptions: “I am quite overwhelmed with all the taffy I get as to my poor letters.” They sent her copies of a Hartford newspaper, which she devoured, “even to the advertisements.”

She and Talcott wound down their trip in Germany. Given Williams’s fondness for Prussian soldiers, Talcott ended up “afraid she will lose me entirely.” Cheap images of the kaiser were omnipresent “in plaster, paint, chromo and photograph.” Berlin museums “have a way of restoring and varnishing that I do not approve of,” but she did deem a Botticelli or two “a perfect wonder” that “carries me far away.” Cologne’s cathedral looked “monotonous (made by the yard and cut off in lengths to suit).” She pitied zoo animals in a heat wave—“I would have been pleased to let out all except the man-eaters”—and overheard Americans spouting “conversation on finances and matrimony that was almost too much.”

In late August she promised to make her way from New York’s harbor to Hartford “as soon as the Custom House fiends let me in.” She mended her worn hats and clothes so they would be “more serviceable for the fall,” and she girded herself for another uneventful semester at Smith College. She took notes on the violent return Atlantic crossing (“Glass and breakables smashed in all directions”) and the sea’s color (“Deliciously blue. The most luminous exquisite tone”). She provided travelogue entertainment for another passenger, the Indianapolis painter and educator Susan M. Ketcham: “Read Miss Ketcham my diary in the p.m.” Ellis Island records for the trip show that Williams and Ketcham proudly listed “Artist” as their profession.

Williams came home elated and never lost her taste for travel overseas. There she could shed her “New England conscience, and just revel in doing pleasant things.” Until a few days before her death (in Florence, due to abdominal tumors), she would hike along European hills sometimes miles a day, seeking sitters or scenery she deemed worthy of a sketch.

This article is excerpted and adapted from Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857–1907 (Wesleyan University Press, 2019).