Because an air of establishmentarian grandeur pervades nearly every aspect of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, it is easy to overlook how unparalleled this institution really is among the museums of the world.

Consider the Met in relation to its peers: the Louvre and the Uffizi, the Rijksmuseum, the Prado and the Hermitage, Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum and the National Galleries of London and Washington. Except for the last, inaugurated in 1941, all of these institutions were founded in the long century between 1765, in the case of the Uffizi, and 1891, in the case of Vienna. But only the Met came into existence, not through imperial fiat or the decision of a national legislature, but rather through the exertions of a group of local merchants and artists far removed from their country’s capital. As such, the Met could not rely on the sustained financial support of a central government, and even the support of its municipality was hardly assured. No great and pre-existing palace invited its occupancy, in contrast to the Uffizi, the Hermitage, the Prado, and the Louvre, nor was a grandiose palace promptly built for it, as occurred in London, Vienna, and Washington. For the first few years of its existence, the Met occupied a fairly humble town house at 681 Fifth Avenue, before it decamped in 1873 to the Douglas Mansion at 128 West Fourteenth Street. Moving to its present location in 1880, the Met initially inhabited a dreary Victorian structure, and many years would pass before it acquired that majestic facade that now unfurls across the finest quarter mile of Fifth Avenue.

The Met was not born full grown, as were the Louvre, the Prado, the Uffizi, the Hermitage, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Notwithstanding their subsequent growth, these museums, from the day of their creation, were among the greatest art collections in the world, having been formed from pre-existing ducal, royal, and even imperial holdings. The museums in London and Washington, though assembled in a more piecemeal fashion, could similarly count on a vibrant substrate of private collections available to be bought or donated. But as regards New York in 1870, there was simply not a great deal of worthy art available to the Met’s founders. Few Old Masters crossed the Atlantic, and those that did were usually of the second rank. Of the inaugural 174 European paintings that the fledgling museum purchased in 1871, only a handful are still on view, among them Anthony van Dyck’s early Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-Stricken of Palermo (1624). The authorship of many more has been called into question and those are now in storage.

The preponderance of the art that greeted the museum’s first visitors was the work of home-grown American masters. A representative example is Frank Waller’s Interior View of the Metropolitan Museum of Art When in Fourteenth Street. Painted in 1881, by which time the museum was already at home in Central Park, it depicts the Met as it had been two years earlier: the date is proved by a painting in the background that a local collector had purchased (and loaned to the museum) as a Da Vinci, but that, typically, was really a crude imitation of the Florentine master. In Waller’s image a fashionable young woman examines paintings hung “salon style,” among which we can make out the aforementioned van Dyck. Little more than a competent academic exercise, Waller’s painting attests to what the Met valued and also to what it was able to buy in the first few years of its existence.

A few months after the Met acquired its first European paintings, it purchased, in 1872, the entire collection of ancient Cypriot artifacts excavated by Count Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who would serve as director of the Met from 1879 until his death in 1904. Although the Cesnola Collection certainly contains some fine objects, the fact that it came from Cyprus, a somewhat tangential outpost of the Greek world, seemed to consolidate a certain air of second-rateness that would not be dispelled until the first great American art collections, those of the Havemeyers, the Baches, and others, began to enter the museum after 1900.

And yet, something important had occurred with the acquisition of Cesnola’s collection. It represented the first major step in the Met’s transition from a fairly conventional gallery of European and local art to the universal museum that we know today, displaying the artifacts of all cultures and all ages. It is true that only a few of the Met’s departments are unsurpassed—among these the American Wing and the impressionist department (although the Egyptian department comes close)—and it is also true that other departments, contemporary art, for example, are relatively weak.

But the achievement of the Met is of a different kind from any of its European competitors. No other institution succeeds in its universal brief as well as the Met: a thorough study of the two million artifacts on Fifth Avenue—if such a study were even feasible in one lifetime—would leave a visitor with a deep and rich appreciation of the arts from ancient Egypt to modern Chelsea, by way of Polynesia, medieval France, and Holland in its Golden Age. Each of the Met’s seventeen curatorial departments—even those that are not pre-eminent—would constitute a great museum in its own right. Through that precise convergence of transcendent universality and almost limitless specificity, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in its sesquicentennial year, stands unrivaled among the great cultural institutions of the modern world.

–James Gardner

The American Wing

The Charles Engelhard Court

Flooded with sunlight and filled with visitors eating, drinking, and hanging around, this is the ideal entry point for considering American art and American democracy.

Art of Native America, the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection

Installed just steps from the Engelhard Court, 116 astonishing objects from more than fifty cultures are at last where they belong in the American Wing.

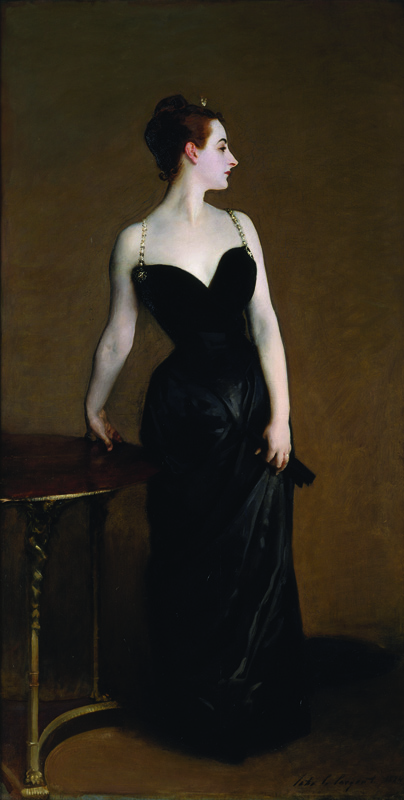

John Singer Sargent, Madame X, 1883–1884

In the thrilling gallery along with Thomas Eakins’s The Thinker and other masterpieces, this really may be the great artist’s greatest work.

Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room

Gilded age opulence is leavened here by the superb craftsmanship of furniture makers George A. Schastey and Co.

Native Perspectives

A favorite example of these commentaries concerns Frederic Remington’s Broncho Buster (1895). Margaret Jacobs (Akwesasne Mohawk) asks an interesting question about Remington’s westward journey.

Robert Laurent carved chest

The oft-told conjunction of American modernism and folk art takes on a dynamic dimension in this example of direct carving made in 1911.

Duncan Phyfe and Sons side chairs, c. 1830

Two rosewood, ash, and tulip poplar chairs are among several pieces in gallery 732 attributed to the workshop of the fascinating man who put New York on the map as the imperial city of furniture design and elegant self-promotion.

Civil War and Reconstruction Eras and Legacies gallery

The paintings and objects here tell an important story, including the imposing Dave Drake storage jar that was recently added to the permanent collection.

American Art Pottery, the Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection

The mezzanine above the Charles Engelhard Court has a huge collection of American ceramics, but this is the collection that always draws me back.

Thornton Dial, Victory in Iraq, 2004

No, like all American art after the early modern period, this masterpiece is not in the American Wing but, as with the rest of our country’s artistic legacy, it should be.

—Elizabeth Pochoda

Classical Antiquities

Marble statue of a youth, c. 590–580 BC

One of the earliest marble sculptures of the human form carved in Greece, this kouros, or young man, is an important example of Hellenic exploration of the male figure in the early sixth century bc.

Marble column from the Temple of Artemis, c. 300 BC

Archaeological treasures that testify to the grandeur of ancient architecture, this Ionic capital and other remnants were part of a column in the Temple of Artemis in the city of Sardis, located in today’s Turkey.

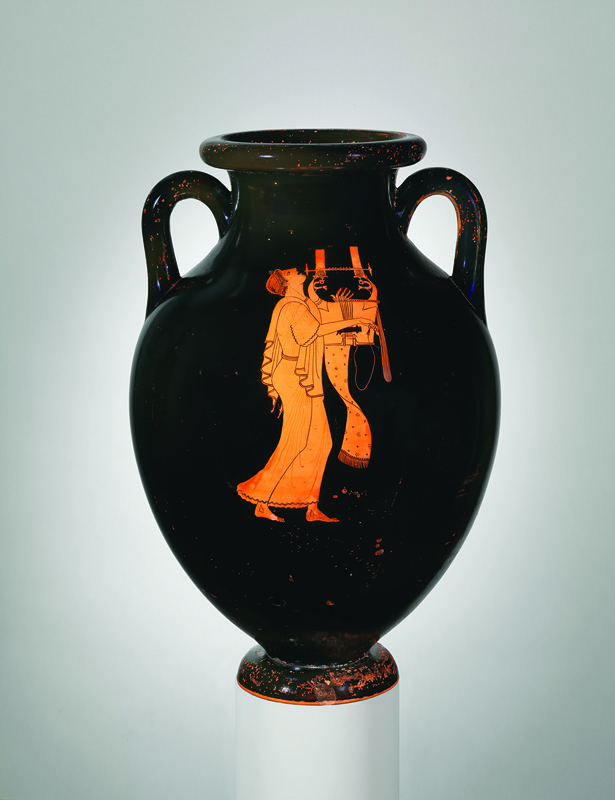

Terracotta amphora, c. 490 BC

A remarkable vase that evokes music and sound through both the positioning of the figure on the curved surface and the dark, unadorned space that surrounds him. This is a wonderful example of ingenuity in vase painting.

—Milette Gaifman, associate professor of classics and the history of art at Yale University

Asian Art

Returning Home by Shitao, China, c. 1695

Choosing works of art from an enormous continent across centuries is not easy! Perhaps my favorite Chinese painting is this one—such a simple work, yet so profound, on the very human theme of dislocation.

Pensive bodhisattva, Korea, mid-600s

Of all the Korean works of art at the Met, this gilt-bronze figure is my favorite. It’s a treasure. The beautiful, serene face would bring anyone a sense of peace.

The Duan Fang altar set, China, late 1000s BC

This extraordinarily rare table and vessel set is considered among the best and most beautiful examples of the complex art of early bronze casting.

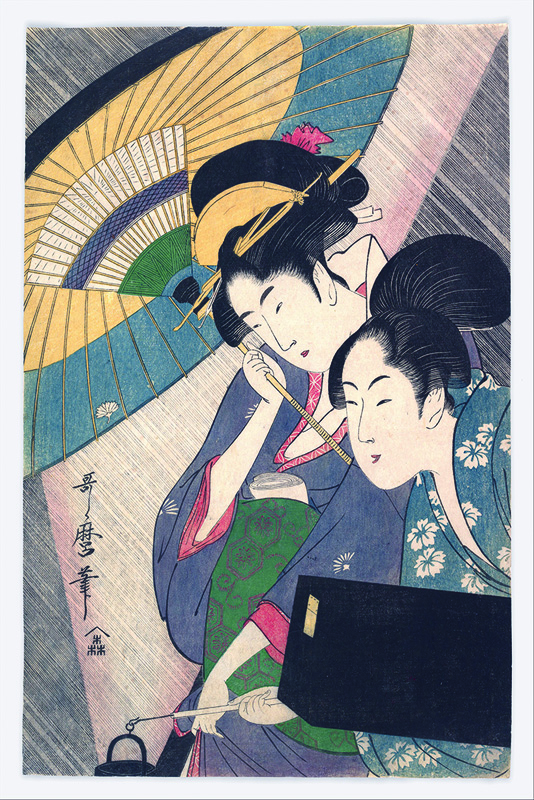

Geisha and Attendant on a Rainy Night by Kitagawa Utamaro, Japan, c. 1797

A fantastic design by arguably the most important artist of the golden age of Japanese woodblock printmaking. It takes my breath away.

Gupta-style Buddha, India, probably 500s

Created during the golden age of Indian art, this form combining idealized divine and human features would influence not only all of later Indian art but that of most of Asia as well.

Mandela of Jnanadakini, Tibet, late 1300s

This incredibly intricate cosmic diagram is from one of the finest series ever painted in Tibet. The mineral colors are as vibrant today as they would have been in the fourteenth century.

—Katherine Martin, chair, Asia Week New York

African and Oceanic Art

Fang reliquary sculptural element, Gabon, Fang peoples, Betsi group, 1800s

This head from a bieri—a guardian figure that protects the remains of ancestors—epitomizes the beautiful carving style of the Fang peoples. It is so simple, yet it evokes a powerful sense of sadness.

Fang reliquary figure, Gabon, Fang peoples, 1800s–early 1900s

This large, female figure is an embodiment of strength and protective power. With her determined stance and her glistening oiled surface, she—for me—is one of the most magnificent Fang figures in existence.

Dan helmet mask, Liberia or Ivory Coast, Dan peoples, 1800s–mid-1900s

This helmet mask from the Dan people is universal in its beauty, refinement, and emotion. It is a classic example of African artistry at its highest level.

Baule standing figures, Ivory Coast, Baule peoples, 1800s–mid-1900s

This pair of beautiful, elegant and serene Baule standing figures reflects the hand of a master carver, with their elongated bodies, regal stances, and the details of their coffee bean–shaped eyes and highly stylized coiffures.

Yimam carved figure, Papua New Guinea, Sepik region, Yimam people, 1800s or before

With its beautiful head, this seven-foot-tall carved figure—a yipwon—stands alone as a pure abstraction of the human form. The surface erosion suggests it may be very old.

—Maureen Zarember, founder and director, Tambaran Gallery, New York

Impressionism

Still Life with Pansies by Henri Fantin-Latour, 1874

Though less well-known than the other impressionists, this artist, both in portraiture and still lifes, is one of the best painters of the century.

The Dance Class by Edgar Degas, 1874

A brilliant evocation of the hectic mix of beauty and discipline at the old Paris Opera.

Young Lady in 1866 by Edouard Manet, 1866

A portrait of Victorine Meurent, clothed in a long white robe (as she was not in Manet’s Olympia and Déjeuner sur l’Herbe).

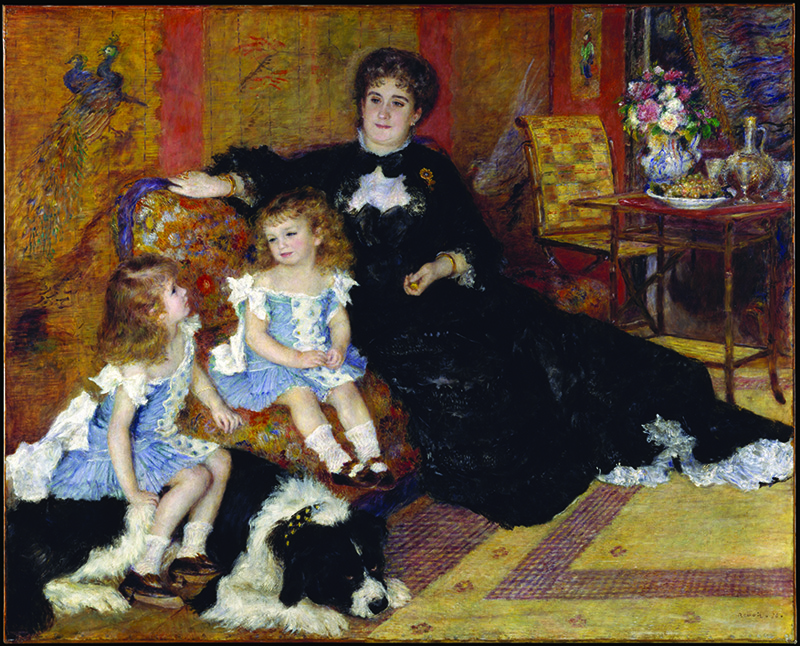

Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children by Auguste Renoir, 1878

A definitive depiction of modern life in an haute bourgeois interior, this is an example of Renoir’s unique brand of sympathetic realism.

Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight) by Claude Monet, 1894

In this mid-to-late example of impressionism, one perceives an almost dreamy symbolist mood.

—James Gardner

Medieval Art

The Unicorn Tapestries, South Netherlandish, 1495–1505

These luxurious tapestries depicting the hunt of the unicorn—full of images of lavish clothes, amusing gestures, and diverting animals, all wrapped in pullulating plant life—are perennial favorites at the Cloisters.

Bowl with Arabic inscription, Nashipur, Iran, 900s

This elegant bowl features Arabic calligraphy so stylized and carefully executed that the letters nearly come to resemble a linear ornamental design pattern. The inscription reads, appropriately: “Planning before work protects you from regret; prosperity and peace.”

The Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, France, c. 1324–1328

The illustrations in this tiny gem of a prayer book were meant to teach a young queen about her role as a pious ruler, though the misogynistic and anti-Semitic images in a few of them are troubling.

—Asa Simon Mittman and fellow members of the historians’ group Material Collective

Modern Art

Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso, 1905–1906

A pivotal work of proto-cubism, the picture’s somber intensity, and the unwavering truthfulness it conveys, inspire a comparison with some of the best portraits by Diego Velázquez.

Nasturtiums with the Painting “Dance” I by Henri Matisse, 1912

Matisse is always there to remind us that art may indeed serve as a beacon of hope, and the last refuge of transcendent beauty. At every encounter, this painting, in full-figure human scale, appears to me as fresh as the first day of spring.

Pianissimo and Fortissimo by Jean Dunand and Séraphin Soudbinine, 1925–1926

Art deco landmarks, these dazzling lacquered screens were commissioned by collector Solomon R. Guggenheim. The stylized, angelic figures—covered in gold leaf and mother-of-pearl, hovering in a teal blue sky—have captivated me since my first Met visit in grade school.

Let My People GobyAaron Douglas, c. 1935–1939

One of the most prominent artists of the Harlem Renaissance, the Kansas-born Douglas connected the story of Moses and the Israelites to the nascent civil rights movement.

Report from Rockport by Stuart Davis, 1940

Stuart Davis’s pulsating tribute to the Jazz Age fuses raucous fauvist colors with quasi-cubist forms.

—David Ebony, contributing editor, Art in America

Old Masters

Madonna and Child by Berlinghiero, possibly 1230s

An exceedingly rare and beautiful example of the Lucca school, which preceded and paved the way for other Tuscan painters such as Duccio and Giotto nearly a century later.

The Crucifixion and Last Judgment by Jan Van Eyck, c. 1400

A cosmic vision in miniature, this perfectly preserved masterpiece reveals the Bruges master at his best.

Portrait of a Member of the Wedigh Family by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532

Perfect artistic self-assurance is achieved through opulent restraint in this image of a Hanseatic merchant.

View of Toledo by El Greco, c. 1599–1600

A cosmic, phosphorescent landscape from a famously wayward Greek master.

The Harvesters by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1565

A masterpiece of genre painting as well as landscape, this tawny image reveals peasant life in the Netherlands in the mid-sixteenth century.

Young Woman with a Water Pitcher by Johannes Vermeer, c. 1662

This delightful interior is as distinguished for its light and colors as for its precise depiction of the real world.

Juan de Pareja by Diego Velázquez, 1650

An outstanding expression of Velázquez’s unrelenting gaze upon his human subjects, this work almost constitutes a vivisection.

—James Gardner