Vermont? Especially, rural, north-central Vermont! Vermont hardly figures in the standard literature on school-girl needlework. While Glee Krueger includes a Vermont sampler in her New England Samplers to 1840[1], Betty Ring’s magisterial Girlhood Embroidery[2] does not mention a single one. Vermont had the least population of all of the New England states, consequently, fewer Vermont needle works were made, and even fewer survive. That demographic factor and general assumptions such as isolation, or ignoring Vermont material culture in general—and especially given that artisans often did not sign their work—reinforce the notion that little was produced there.

Needlework, however, should be the exception for it is typically signed by the girl, or young woman, who made it. In addition to the makers name, samplers, unlike memorials or works on silk, often include age, birth-date, date of completion, and place—town, even county and state. A few mention the name of the maker’s teacher. Silk embroideries may append the name of the maker, and sometimes the title for the image depicted, but little more. Consequently, the focus is more on the image and the skill of the maker rather than on the maker, herself.

In the example here, the name “Hester Leavenworth” is not found on the embroidery, but on its verre églomisé and in gold rather than silk threads. The original backboard lists the embroidery’s subsequent history in the Miller and Leavenworth families, which reinforces her place of origin. Genealogical research establishes that Hester, or sometimes, “Hetty,” Leavenworth was born 4 August 1796 in Hinesburg, Vermont, into one of its prominent families. Her father was General Nathan Leavenworth (born 20 Aug. 1764/5 in New Milford, CT, and he died in Hinesburg 8 Sept. 1849) and her mother, Anne Buckingham Leavenworth (1770-1805) of New Milford; they were married 1 January 1793. Three years later, in 1787 they moved to Hinesburg, where General Leavenworth farmed and served in various local and Vermont state offices.

Hester married Henry/Harry Miller of Williston—just to the north of Hinesburg—from another prominent Vermont political and farming family, 2 October 1816. Hester died 27 February 1864, without surviving children, and is buried in the Miller family plot in the Thomas Chittenden Cemetery in Williston. Harry/Henry Miller was a farmer, and served in the Vermont state senate in 1836 and 1837.. His father, Solomon Miller was a member of the Governor’s Council beginning in 1799, as well as a representative, clerk of the courts, register of probate, and judge of probate.

Several major challenges remain for this silk embroidery: was it actually made in Vermont? First, silk pictorial embroideries were only produced in a few elite schools.

“The creation of these ornate [silk] pictorial embroideries became one of the major tasks of young women attending female academies. Only the best and most expensive schools and instructors could teach this fine form of decorative needlework. The ability of a family to display the framed embroidered pictures in their parlor proclaimed not only the skills and accomplishments of their daughter, but their socio-economic ability to afford the expensive schooling needed to produce such work.”[3]

Clearly, Hester Leavenworth’s embroidery, expensively framed in gold gilt and with a verre églomisé, gives evidence of her family pride and status. But where, when, and under what circumstances might have Hester’s acquired her skill?

Elements of Hester’s embroidery can possibly be seen in the depiction of a stream between similar trees in “Figure 21: Mourning Picture” from Miss Pierce’s School in Litchfield, CT[4] and in Ann Marie Treadwell’s watercolor of “George Washington at Mt. Vernon,” and documented to 1814 and “Mrs. Willard’s School,” Middlebury. And together, they suggest an answer to Hester’s education question.

Given Hester’s elite family status and that Hinesburg was ca. 24 miles from Middlebury, where the first schools for girls in Vermont, the Middlebury Female Seminary, was founded in 1800, she could very well have developed her needlework skills there. In addition, Idea Strong, the founder of Middlebury’s Female Seminary, was educated at Miss Pierce’s School which was known for its excellence, including fine needlework. Middlebury’s Female Seminary developed a high reputation and was based on Litchfield Female Academy; indeed, Sarah Pierce directly oversaw its initial establishment.[5] Interestingly, from 1807-1808, Emma Hart of Berlin, CT would lead the re-opened Middlebury’ Female Seminary and after her 1809 marriage to Dr. John Willard, she established her own school in Middlebury, 1814 -1819, before she moved it to Troy, NY in 1821, and subsequently, the Emma Willard School.

It is even possible that Hester Leavenworth went to Miss Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy in CT, although, her name is not to be found on its extant but incomplete list of students, including some from Vermont; moreover, Hester Leavenworth’s parents were from New Milford, CT in Litchfield County and other Leavenworth names are to be found in those lists. Middlebury’s Female Seminary is, however, the more likely place for Hester’s embroidery, although Litchfield, or even the possibility of a yet unidentified girl’s school in Burlington, VT—some 15 miles from Hinesburg and a major city linked to Montreal—cannot be ruled out.

Intriguingly, Hester’s much younger half-sister, Rachel Lucretia Leavenworth (1810-1886), was born to General Leavenworth and his second wife, Betsey Hurlbut Leavenworth, and was sent to Emma Willard’s school in Troy. This suggests a family link to Emma Willard in Middlebury, if not the earlier Middlebury Female Academy. Evidence, also, notes that Rachel’s education “ . . . was pursued in her native town, and in Burlington, up to the time of entering Troy Seminary, where she passed the school year ending in 1830.”[6] Despite the reference to Hinesburg and Burlington, where Hester might, too, have received her education, Middlebury, or Litchfield, remains the more likely place where she learned and completed her costly embroidery.

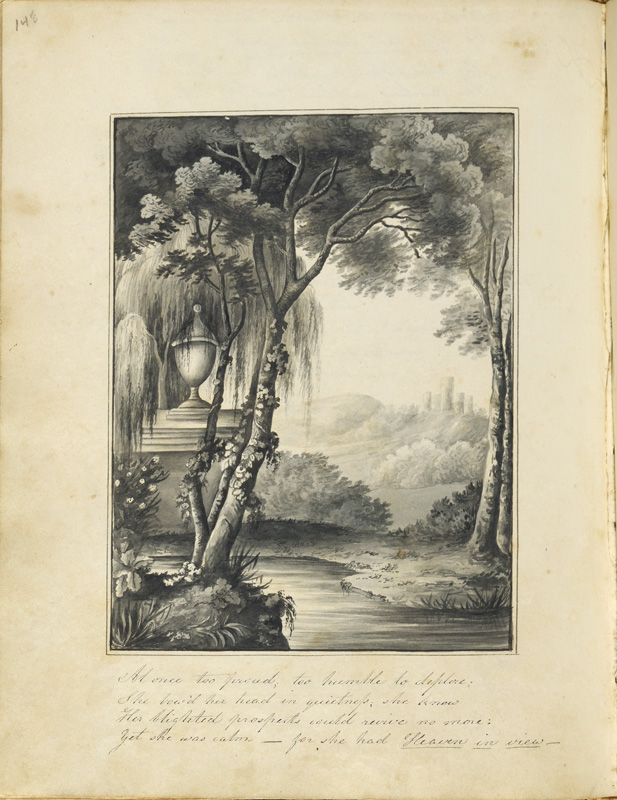

Second, when might the embroidery be dated, and could identification of the highly romantic image help in doing so? The embroidered/water-color image depicts an elegantly dressed weeping woman standing by a meandering stream in a parkland setting with it distinct trees. Easy to overlook is that she is being surreptitiously observed by a young man whose head and shoulders appear in the branches of one of the trees. A print source has yet to be located, but the figure of the weeping young woman does bring to mind “weeping” Charlotte from Goethe’s “Werther,” which was widely translated and sensationally popular after its original publication in 1774 as Die Leiden des jungen Werther, or The Sorrows of Young Werther. The problem is that there is no reference in the novel to the scene on Hester’s embroidery, or in the many related prints, where Charlotte is always shown as weeping at Werther’s tomb.

In this age of romanticism—the period of Hester’s embroidery—there were, however, many “Werther” adaptations, one of which was Werter and Charlotte. The Sorrows of Werter. A German Story. To which is Annexed the Letters of Charlotte to a Female Friend during Her Connection with Werter (Boston: Thomas and Andrews, 1798) that was reprinted several times and places in the United States. In the last of her letters here, Charlotte writes:

“Letter LXIII [from Charlotte]: I have heard [sic. read] his last letter! I have wept over every endearing recollection: Albert [Charlotte’s ultimate husband] joined his tears with mine; he will build a tomb to perpetuate the memory of Werter’s love to Charlotte . . .

“O, Werter! Why do you call to my remembrance the scenes that are past? I vain shall I look for you in the valley! What will it avail, in a summer’s evening, to walk towards the mountains, or repose me under the elms? Shall I see your spirit in the pale clouds, or hear your voice in the passing winds? . . .

“. . .We shall meet no more in the groves of Walheim [river]! No more shall we see thee musing by the river in the valley. . . .

“ At the corner of the church yard, which looks towards the field, there are two lime-trees. There rest thy remains, O Werter! My father lays thee in the appointed place. There will Albert build thy tomb. . . .”[7]

Is that then, Werther’s spirit among the tree leaves, and weeping Charlotte recalling his presence “by the river in the valley . . .?”

Hester married in 1816 when she was 20, so the work was framed before then given that the verre églomisé specifies “Hester Leavenworth, ” Hester’s work can likely be dated to between ca. 1810 -1815, when she was ca. 14-19. Is it more likely that a 16-19-year-old would have been reading Werter and Charlotte? The Sorrows of Werter. . . than a 14-year old? This would support the later date for the embroidery. Other than the name of the embroiderer, “school,” subject, and date cannot be definitely established, only suggested. Hinesburg, Vermont, however, was not so isolated, and in the case of Hester Leavenworth, linked to Litchfield, CT by family and probably through Middlebury—by either its Female Seminary, thus, indirectly to Miss Sarah Pierce’s, or Mrs. Emma Willard’s School similar to it—and to contemporary romanticism, likely, even to Goethe’s Germany. Many, many French knots and satin stiches in silk threads on silk tie Hester’s “Vermont” embroidery to an even broader world—Goethe’s “Werther” was translated into Chinese where some of its silk and silk thread could well have originated.

[1] Glee Krueger, New England Samplers to 1840 (Sturbridge: Old Sturbridge Village 1978). Krueger does list three schools in Vermont—Newbury, Norwich, and Windsor—but not the Middlebury Female Seminary, the first, founded in 1800. Ibid., p. 205. [2] Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (New York: Knopf, 1993). [3] “Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy,” by Lynne Templeton Brickley in To Ornament Their Minds: Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy 1792-1833, ed. By Catherine Keene Fields and Lisa C. Kightlinger (The Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, CT, 1993), p. 54. [4] To Ornament Their Minds. . . p. 59. [5] “When in 1800, Moses Seymour left Litchfield to marry former Academy student Mabel Strong in Addison, Vermont he brought Sarah Pierce and her former pupil and assistant teacher, Idea Strong, with him to open a school for women. Sarah Pierce stayed to see the Middlebury Female Academy successfully established under Idea Strong. Sarah Pierce’s reputation as a teacher with the leading families of Vermont, many of whom were originally from Connecticut and had sent their daughters to her school, assured the success of the Middlebury school, which based its program closely on the Litchfield Female Academy model. The school was known for the teaching of the “higher branches” and attracted students from throughout Vermont and upstate New York. After Idea Strong’s untimely death in 1804, Emma Hart of Connecticut was invited to take over the school. Emma later married Dr. John Willard and moved to Troy, New York, where she established the Troy Female Seminary in 1821.” Ibid., p. 72.

See. Also: Samuel Swift, History of the Town of Middlebury . . . (Middlebury, A. H. Copeland, 1859), pp. 391-397.

[6] Mary Mason Fairbanks(Mrs. Russell Sage), Emma Willard and Her Pupils: Or, Fifty Years of Troy Female Seminary, 1822-1872, (Mrs. Russell Sage, 1898), p. 75. [7] [Possibly William James], Werter and Charlotte. The Sorrows of Werter. A German Story. To which is Annexed the Letters of Charlotte to a Female Friend during Her Connection with Werter. The Whole of both works in one Volume. (Boston: Thomas and Andrews, 1798) pp. 283-284.Gene R. Garthwaite, a collector who lives in Hartland, Vermont, is an emeritus professor of history at Dartmouth College.