Timepieces made by members of the Willard family of Grafton, Massachusetts, in the early decades of the American republic have long been held as masterpieces of artisanship and industry. Popularly known as banjo clocks for their characteristic shape, they were the first timepieces to be made entirely—that is, both clockworks and case—within the new United States. The Willards’ creations marked a notable break from American reliance on European, and particularly British, fine trade goods.

Over the centuries since they were made, Willard clocks have maintained their position as a classic choice for decorating traditional homes. Such accolades and lasting power may lead to the assumption that the engineering of these pieces was, in one way or another, exceptional. Such conclusions would be wrong, says Robert C. Cheney, executive director and curator of the Willard House and Clock Museum. When asked what it is about the Willard timepieces that makes them masterpieces, he answered with only a moment’s pause: “Well . . . I don’t consider them masterpieces.” The mechanisms within the Willard timepieces, he reports, are “really, clockmaking 101.”

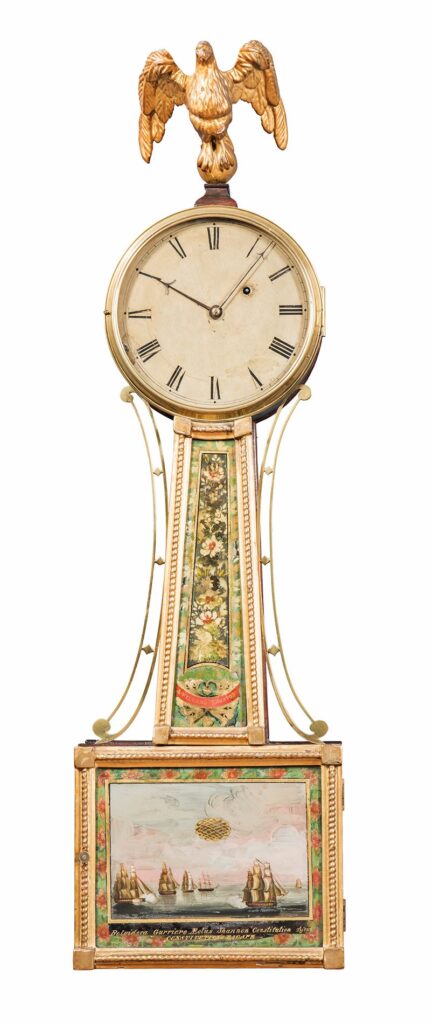

Roxbury, Massachusetts, the original eglomise glass tablets with Father Time (see detail), attributed to John Ritto Penniman (1782–1841) of Boston, Massachusetts, 1805– 1815. Gilt hardwood, brass, iron, and glass; height 34 inches. The throat is inscribed “WILLARD’S PATENT.” Photograph courtesy of Nathan Liverant and Son, Colchester, Connecticut.

That is not the kind of reply one expects from the curator of a museum dedicated to said “clockmaking 101” timepieces. But, as Cheney is a third-generation horologist with more than fifty years of experience in antique American clocks and timepieces, he knows his business. Why, then, all the hoopla (both then and now) about the Willards and their works?

For the Willards, clockmaking was a family affair. The four brothers, Benjamin, Simon, Aaron, and Ephraim, were all clockmakers, and active in the Boston area from the 1760s into the 1840s. Their designs and manufacturing process set off a fundamental shift in timekeeping in the United States, helping to bring the accurate delineation of time into the homes and work- shops of a wider range of individuals. Three successive Willard generations followed them into clockmaking and horological development.

It must be remembered that, in the late eighteenth century, clocks and timepieces—shorthand on the difference: a clock chimes, a timepiece doesn’t—were the reserve of the very wealthy. A clockmaker was an incredible artisan who had to make machines that ran, well, like clockwork. This was an extremely difficult task, and came with a commensurate price tag. In the late eighteenth century, a clock would easily be the most expensive item in a household if one could be afforded at all. In the year 1774, in New England and the Middle Atlantic colonies, fourteen out of a hundred people, on average, had a clock among their possessions when they died. In the southern colonies, only about six in a hundred owned one. The Willards saw how few of their countrymen could afford a means of keeping time and they resolved to devise a method to make them more accessible.

Pre-Willard, American clocks were multi-maker affairs, with the cases being made-to-order by cabinetmakers and other skilled carpenters, then handed over to the clockmaker. This was inefficient and expensive. Rather than waiting for a client to approach them to commission a clock, the Willards produced the cases and works in advance of orders, and then sold complete pieces from their ready stock. They also took commissions, but they were the first to build a business model that made room for spur-of-the-moment shoppers. Because of the streamlined production, they were able to sell many of their pieces at far lower prices. According to Cheney, some of their clocks cost as little as ten dollars in the 1830s.

The Willards’ efforts to decrease price by centralizing production had an unforeseen benefit: they were able to innovate and experiment within a controlled environment. In November 1801 Simon Willard sent something new to Samuel A. Otis, who was then serving as secretary of the Senate of the United States. Otis took it upon himself to present Willard’s creation to the patent office in Washington, DC. Following formal registration and a thirty dollar application fee, Simon Willard was granted a US patent for his “Improved Timepiece,” which would in time come to be called Willard’s Patent Timepiece.

signed by Simon Willard Jr.,

Boston, 1830. Gold, brass,

steel, and enamel dial;

diameter 2 inches.

Willard House and Clock

Museum photograph.

The patent timepiece was a compact (about three feet tall) wall-hung timekeeper that was accurate, dependable, economical to produce, and attractive. “The banjo clock is elegant—truly elegant,” says Arthur Liverant, third generation owner of Nathan Liverant and Son Antiques of Colchester, Connecticut. With its creation, Simon Willard concretized the independence of American clockmaking. Four thousand authentic Simon Willard patent timepieces were made, though he allowed his brothers and close associates to use his design.

Many patent timepieces featured painted decorations of flowers and foliage, gilding, and beautifully carved details. Cheney insists, though, that the finest examples have a looking glass mounted in the middle portion of the timepiece in lieu of a painted scene. “The looking glass would reflect candlelight into the room, helping to illuminate the space and to bring more light in,” he says. “They were wonderfully attractive.” Alas, very few of these timepieces remain unaltered. In his fifty years of studying the Willards’ work, Cheney has seen only two that retained their original looking glass panes. “Many,” he says, “were stripped out by dealers in the 1920s and ’30s who thought, ‘they wouldn’t have had that,’ or ‘that won’t sell like that,’ and put in clear glass.” Today, it’s the decorative details, like original glass and painted panels, that make a Willard so striking.

Cheney advises aspiring collectors to “know what you are getting into.” Numerous factors affect value, which fluctuates wildly depending on condition and the subject, execution, and state of the decorative elements, and many original Willards have significant issues with their mechanisms. Some have been damaged by negligent or careless use, and the glass on the timepieces is particularly fragile. As Liverant remarks, in the world of antique clocks “it’s all about condition, condition, condition.” As a result, the value can range wildly. “Originality is key,” Liverant says, “but so are the details.”

Whether in immaculate shape or in need of repair, works by the Willards are highly valued pieces of American ingenuity and design. A very fine example of a Simon Willard patent timepiece sold at Sotheby’s in 2018 for $21,250, while another by Simon sold at Skinner’s auction house in 2020 for $33,750. They have been a show-stopping fixture of the American decorative world since their creation—masterpiece or not.