The generally shameful human compulsion to try to frustrate, confuse, and vex our fellow bipedal creatures has, at least, one charming manifestation: the puzzle jug.

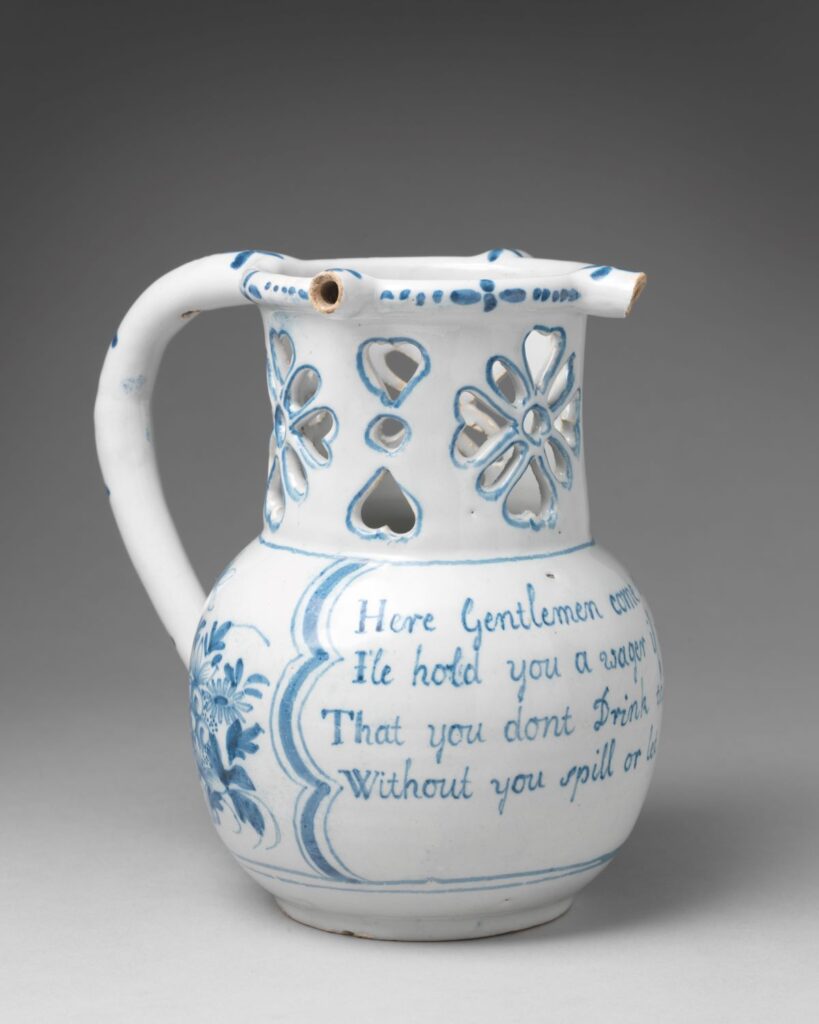

For centuries in Europe, wine and ale were served at table in jugs, when such beverages were stored in casks rather than bottles in homes and taverns. At first glance, a puzzle jug appears to be, well, a jug. Made of glazed and decorated clay or porcelain, the puzzle jug has all the normal jug components: handle, shapely body, neck, spout. But beyond that our puzzling pal is nothing like an ordinary vessel. A typical puzzle jug might have not just one spout, but two, three, or even four. More confusingly, the neck, as if to mock jug function, has holes cut through it all around, rendering the normal method for pouring completely useless. Any attempt will lead to a very wet table or clothing, and it seems as though the jug knows all too well the ramifications of its design. Indeed, many puzzle jugs flaunt their undrink-ability. The decoration may even apprise the drinker of the challenge, such as that on one example in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with a painted rhyme on its belly that reads:

Here, Gentlemen, come try your skill

I’ll hold you a wager if you will

That you don’t drink this liquor all

Without you spill or let some fall.

If a player were observant and careful, they could, through trial and error—or by watching the trials and errors of others—decode the secret to the vessel that lay in its construction. In one popular form of puzzle jug, the potter crafted the top rim and the handle from hollow tubes of clay and connected them together. The handle tube ran to the bottom of the jug with an opening to the vessel’s interior, creating a kind of built-in straw. A drinker could suck on one of the spouts on the rim—just one of the multiple spouts worked—to draw up wine, but only if he knew the real solution to the puzzle jug: that an airhole on the underside of the handle had to be covered with a finger to produce suction.

The above describes a relatively simple puzzle jug. “Some of the puzzle jugs are quite challenging,” says Leslie Grigsby, the curator of ceramics and glass at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. Some jugs might have false airholes, or might have a second or third true airhole hidden in carvings or decorative glazing. A run-of-the-mill puzzle jug was likely owned by a tavern and, as inscriptions on some indicate, available for rent to pranksters. Those made by the best artisans, however, were tours de force—demonstrations of the highest skills. Seventeenth-century potters in the Dutch town of Delft seemed to take special pride in puzzle jugs, to judge by the novel shapes, delicate piercing, and intricate glazed decorations they produced. A marvelous video produced by the Victoria and Albert Museum, and easily found online, documents the celebrated contemporary ceramist Michelle Erickson building a puzzle jug, and proves how demanding a form it is.

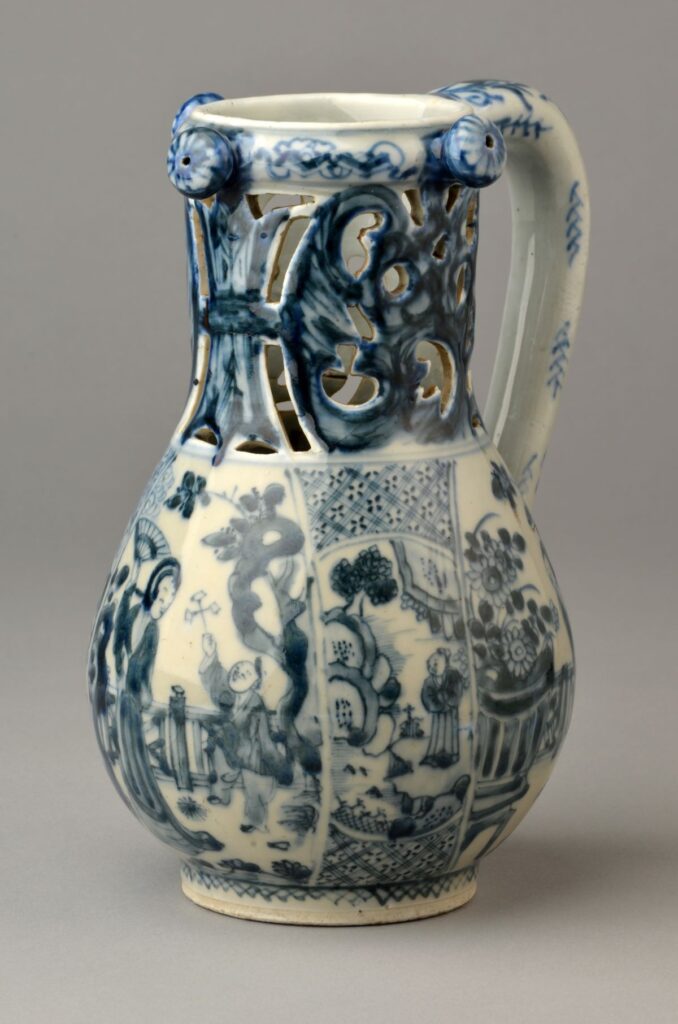

There are perplexities embodied in puzzle jugs for art historians as much as for drinkers, as demonstrated by two jugs held by Winterthur. The first was brought to Europe via the trade network with Japan. Produced in Arita, Japan, between 1690 and 1710 for export to the European market via the Dutch East India Company’s vessels at Nagasaki, its painted decorations are done in a Dutch style but are copies of typically Chinese scenes, according to Grigsby. “What we see here is a Japanese imitation of a Dutch style decoration with an imitation Chinese motif.” It is a very international piece of work, especially for the late seventeenth century. That this piece should also be a puzzle jug, following a common English design for the jugs, is also remarkable, and the piece showcases the coordination and complexity of the international porcelain production supply chains of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Another star of the Winterthur collection is a puzzle jug in lusterware, likely made in Staffordshire, England in 1814. This piece was decorated in imitation of far more expensive silver vessels that were popular during the period, but the “silver” decorations were made by applying tarnish-proof platinum atop the jug’s glazed pearlware body. To put it plainly, someone wanted to look fancy. The jug bears the name of its original owner and a date, likely indicating it was a special commission. Within the openwork belly of the jug, a small figure of a lion gazes out. These privately commissioned pieces were not intended as rentable games to be picked up and tossed about by any old fellow at the pub. Rather, they were meant to honor an individual, likely on an important occasion. This seems to speak to a truly wide-spread popularity of the form up and down the socio-economic ladder.

Perhaps the most remarkable element of the puzzle jug story is the sheer longevity of their popularity. The earliest known example dates to thirteenth-century France. Puzzle jugs reached their peak of popularity in the late seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries, though the form continued to appear well into the mid-twentieth century in the United Kingdom. (If we are willing to expand our definition of trick vessels a little further, there are ancient Greek cups that push the timeline back to the days of Pythagoras in the sixth century bc. So perhaps, just about as soon as humans discovered that they liked drinking alcohol, jokers began creating ways to make it slightly more difficult to imbibe. Truly, the more things change, the more they stay the same.)

At auction, puzzle jugs range widely in price, sometimes selling for around $500, sometimes for as much as $23,000. An excellent Delftware jug from a specialist such as Aronson Antiquairs costs $25,000. Decoration, condition, and place of origin all play a role. Despite the wide range, there’s nothing puzzling about the popularity of these curious pieces.