from The Magazine ANTIQUES, April 2009 |

What collector of American art, new or experienced, would not relish owning a work by Edward Hopper? Given the six- to eight-figure prices Hopper’s paintings command, is this a pipe dream for anyone except the very wealthy? Not necessarily. Because etchings are printed in multiples, they offer the new collector an opportunity to own work by a desirable artist for a more affordable price than paintings or drawings.

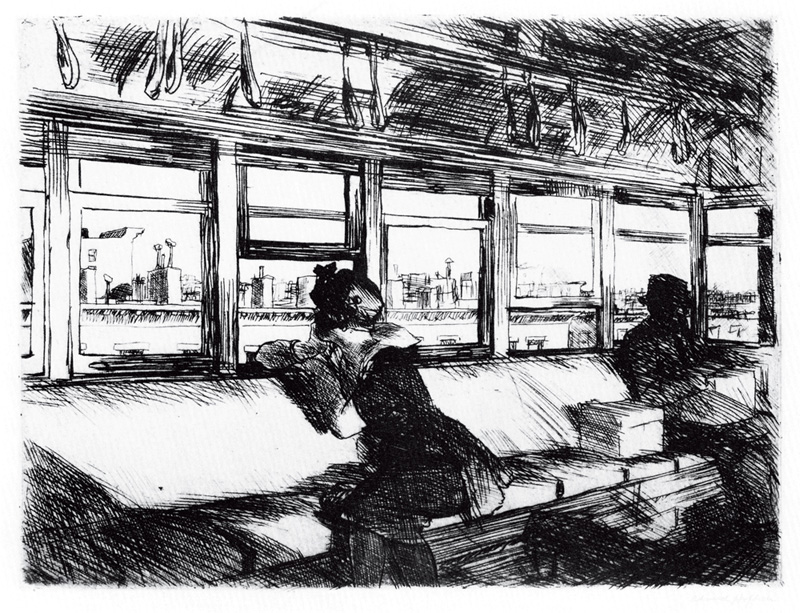

Hopper proved a master etcher early in his career. Around 1915 he began to produce a small but vivid series of etchings that captured everyday New York life. His 1921 House Tops, illustrated here, which was recently featured in a fine Hopper show at the Craig F. Starr Gallery in New York, reveals not just his keen ability to create a memorable composition from a mundane scene, but also how well this medium suited the economy of line that is at the heart of his draftsmanship.

An appreciation of an etching as fine as House Tops could make anyone into a collector, but there are important things one needs to know and to consider before launching upon a collection.

Methods

Etchings are a form of intaglio. Intaglio refers to print methods in which the lines to be printed are engraved into a metal plate. In straightforward line engraving—such as the steel engraving of United States paper currency—the engraver slowly and painstakingly cuts directly into the metal plate with sharp tools called burins, pushing them along the plate to produce designs composed of patterns of lines (called hatching), crisscross textures (cross-hatching), and dotted textures (stipple).

Etching, however, allows the artist to work with a lighter, freer hand because he does not cut directly into the metal but only into an acid-resistant ground: A polished copperplate (or less ideally zinc) is coated on both sides with a ground of dark varnish or smoke-darkened wax, onto which the artist draws his design with a steel etching needle. As he draws, the needle exposes the metal underneath, and this ease of handling allows artists to draw with tremendous spontaneity, almost as they would draw on paper.

Once the needle-drawn design is complete, or advanced enough to satisfy the artist, the plate is bathed in a nitric acid solution, which etches, or “bites,” the exposed metal lines, forming grooves and leaving the grounded portions unetched. The longer the plate is in the acid bath, the deeper the grooves and the heavier the lines will print.

The plate is removed from the acid bath and wiped with a solvent to remove the remaining ground from the rest of the plate. Ink is then rubbed over the plate into the etched grooves and the plate is wiped with a rag, leaving the ink in the grooves and removing it to a greater or lesser degree from the smooth surfaces of the plate. Many artists achieve subtle toning or patination effects by carefully manipulating the residue ink on the smooth metal areas, a process that can make every printed impression of an etching differ slightly from the others, though Hopper preferred to wipe the plate clean to achieve the greatest possible contrast.

A moistened sheet of paper is laid over the inked plate and blanketed with several layers of felt. The whole sandwich is run through an intaglio press, its tremendous pressure forcing the ink from the grooves onto the paper. The artist carefully removes the felt, peels the paper from his plate, and sees his etching, which naturally contains the design printed in reverse. If pleased with the resulting proof impression, he can run an edition of a predetermined number, signing and numbering them.

States of a plate

If the artist wants to work the plate further—adding new elements or strengthening others—he applies a new ground and repeats the process, the next batch of proofs or prints being called the second state. Further changes yield further states until a final state is reached. Etchings frequently exist in several states, and expert dealers, who know which pictorial elements are evident in or missing from the various states, usually cite the state when describing a print for sale.

Drypoint

To darken and intensify certain lines, artists will sometimes augment passages of an etched plate in drypoint, cutting directly into the metal instead of immersing it in the acid bath. As the artist draws with the drypoint needle, it throws up a little ridge of copper on each side of the line, which prints an intense, somewhat clotted black effect called the burr. These copper ridges wear away after only a few printings, so the intense burr only lasts for a few prime impressions, and experts can often determine whether an etching is an earlier or later state by comparing the intensity of any drypoint lines (weaker impressions tend to mean later impressions), or noting their absence (which means an earlier state before they were added). Some prints are executed entirely in drypoint, but when a print is described as etching with drypoint, it means that both techniques were employed.

Hopper and others

As an etching, Hopper’s House Tops masterfully exhibits the best qualities of the medium-the fineness of his lines and their cumulative textures yield vibrant contrasts of light and shadow. As a tour-de-force by one of America’s greatest artists, House Tops would probably sell for between $50,000 and $75,000. Hopper is admittedly expensive, but etchings of urban and country vignettes by his contemporaries are more affordable. Among these, Starr notes that works by Hopper’s friend Martin Lewis (1881-1962), who gave Hopper technical advice on etching, are available for under $50,000, and some can be found for prices under $25,000. Other leading names include Childe Hassam, some of whose etchings can be found for under $10,000, and, John Sloan (1871-1951), whose New York scenes can be found for prices under $5,000 and even under $2,000. (Our second illustration shows Hassam’s 1916 etching Madonna of the North End, one of his Boston scenes. As of this writing, this impression—signed with the artist’s monogram—is available for $3,500 at the Old Print Shop in New York.)

Etchings by lesser known contemporaries in a similar style are even more affordable, among them Stephen Parrish (1846-1938), Roi Partridge (1888-1984), Horace Devitt Welsh (1888-1942), and Louis Orr (1879-1961), many of whose works can be had for well under $1,000.

Tips

❖ It may sound obvious, but it makes sense to spend time in museums, galleries, and libraries to get an idea of what the best things look like. It is also a good idea to become familiar with the specific visual quality of the inks and papers used by master artists.

❖ Gallery owners are happy to encourage new collectors and to show them affordable things in every field. Many leading print dealers belong to IFPDA, the International Fine Print Dealers Association, whose Web site (www.printdealers.com) is a trove of useful information. Presale exhibitions at auction houses are also excellent places to get experience examining prints.

❖ Read widely about etching and its practitioners. Often there is a monograph or catalogue raisonné of an artist’s prints that will show good examples and often point up fakes.

❖ Use a magnifying glass when examining any print of interest for sale. Make sure it reveals the raised lines of intaglio ink against the surface of the paper.

❖ Again using a magnifying glass, make sure the plate marks are visible. All intaglio prints bear a plate mark, an impressed line around the perimeter of the image, formed by the edge of the plate under pressure. The paper surface outside the plate mark is noticeably thicker than the compressed surface within the plate mark. For collectors, plate marks are crucial identifiers. In general, if a print being offered as an etching does not bear one, be wary. Admittedly, old etchings have sometimes been trimmed inside the plate marks, but reputable dealers and auction experts mention this in their written description of the print.

❖ Is the print signed and numbered in pencil, or just signed in the plate? Early prints were not signed by hand, though artists usually etched or engraved their name or monogram on the plate itself. In general, from about 1880 artists commonly signed their prints in pencil, ink, crayon, or with a personal stamp. A pencil or stamped signature means the artist himself printed or at least approved the impression. Hopper did not number his impressions, but printed as he needed to, usually limiting the number to one hundred. Other artists had different habits. Prints of this period lacking a pencil signature may well be impressions from the original plate but not authorized by the artist. These “restrikes” should be cheaper than prints signed by the artist.

❖ Learn about collector’s marks (where apparent), which can help to identify the provenance of the print.

❖ If the lines themselves appear flat and uniform with the paper surface, and the entire composition is composed of tiny dots-like those of the illustrations in this magazine—you are looking at a reproduction called a halftone, not an original print. The same is probably true if the image is printed on coated paper like magazine stock. A good halftone can even reproduce a pencil signature convincingly to the naked eye, thus the importance of the magnifying glass.

❖ Consider taking a course in printmaking since nothing beats hands-on learning.

❖ For important information, check Web sites of institutions with good print departments, such as the New York Public Library (www.nypl.org) or the Indianapolis Museum of Art (www.imamuseum.org).