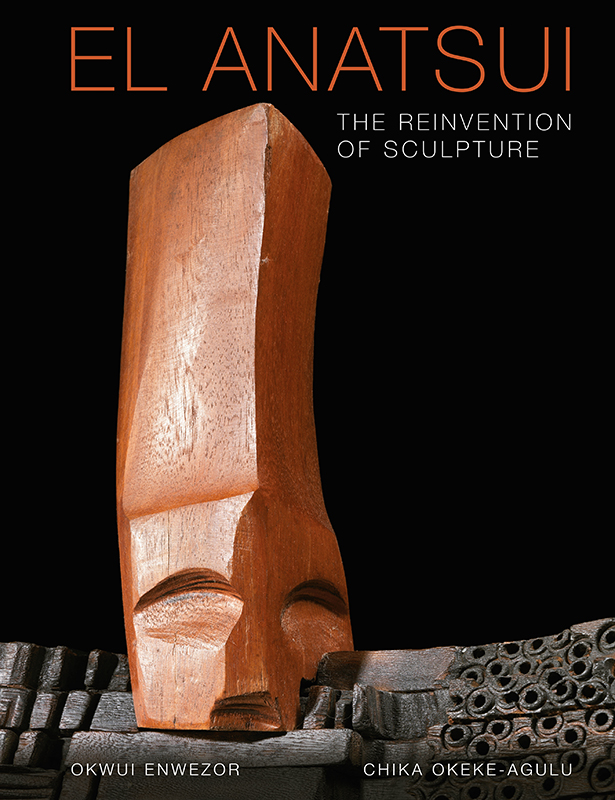

The acclaimed Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui represents an inspired fusion of craft and fine art. Evoking the aesthetic principles of arte povera, the art movement that sought to fashion beauty out of found natural objects and the detritus of the postwar world, he has transformed objects such as soda cans and discarded timbers into monuments rich in history and the intimation of transcendence. Now, at seventy-eight years old, he is the subject of a hefty book, El Anatsui: The Reinvention of Sculpture, by Chika Okeke-Agulu and the late Okwui Enwezor.

The authors are at some pains to situate El Anatsui’s work within the visual and cultural traditions of Ghana and Nigeria (where he has spent much of his career), while at the same time stressing the limits of his dependence on those forebears. What is hardly stressed at all, however, is the ease with which the sculptor can and must be understood within the context of Western modernism. His art is not to be seen as indifferent to that tradition, let alone as rebelling against it, but rather as extending and revitalizing it in an unusually fertile way. That is to say that El Anatsui, over the span of half a century, has progressed from a committed modernism—with a reverence for form as well as for those post-colonial concerns that the book ably expounds—to a postmodernist emphasis on installation and the experiential aspects of his art.

Some of his earlier works (such as Omen from 1978, a grayish gourd made of stoneware and manganese with a perforation at the top, or Imbroglio from a year later, its tangled cords fashioned from the same materials) exhibit many of the formal and thematic preoccupations of mainstream modernism, although in a highly accomplished and original way. A decade later, El Anatsui made the transition to wood. Wonder Masquerade II (1990) and Erosion (1992), with their charred or worn totemic forms, invoke both traditional African spirits and the remnants of industrialization. They are the steppingstones to the installationoriented works of more recent years that represent El Anatsui’s best and most original art.

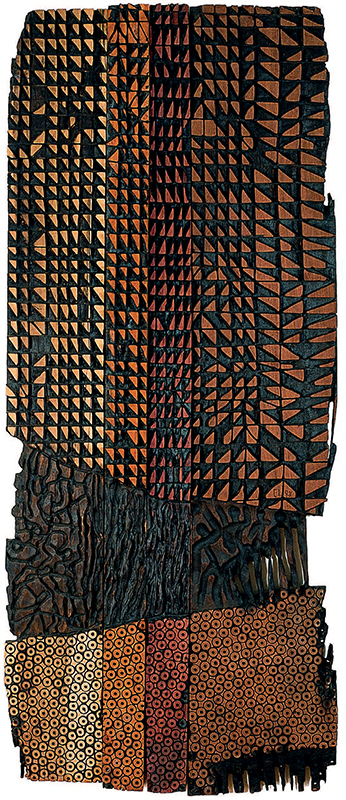

A crucial link between Wonder Masquerade II and what came later are the expansive wooden panels in the Grandma’s Cloth series and the Old Cloth series, from 1992 and 1993, respectively. Inspired in part by the brightly colored kente designs of traditional Ghanaian textiles, with their insistently modular patterns, they also recall the gestures and formalism of the New York school and the wooden sculptures of Louise Nevelson.

But even if there is a continuum between El Anatsui’s earliest and latest work, little in the former prepares us for the elevated richness and refinement of what he has been making lately. His main inspiration comes from discarded beverages, whether from the sawed-off tops of soda cans, the transformation of those cans into aluminum strips, or the gaudy gold foil that surrounds the necks of champagne bottles and the like.

Thousands, if not tens of thousands, of these discarded elements have been culled and reconstituted to make such shimmering, abstract tapestries and cascading installations as Between Earth and Heaven (2006) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Gravity and Grace (2010), a polychrome expanse of aluminum and copper wire. In the latter, whose title is derived from the writings of Simone Weil, El Anatsui remains faithful to his African roots and to the proletarian aesthetic of arte povera, even in his pursuit, in his words, “of the material and the spiritual, of heaven and earth, of the physical and the ethereal.”