With the publication of Bronzino’s Ludovico Capponi and Rosalba Carriera’s Man in Pilgrim’s Costume, the Frick Collections’s Diptych book series now comprises thirteen titles. Each of these elegant, cloth-bound volumes, of uniform format, is dedicated to a single object in the museum’s permanent collection, with considerations of that object by one of the museum’s curators, writing from an art historical perspective, and by a writer or visual artist who responds in more personal terms. The pairing of these two participants explains the concept of the diptych in the title of the series, which, at $24.95 per volume, seem moderately priced for artbooks as lavishly produced as these.

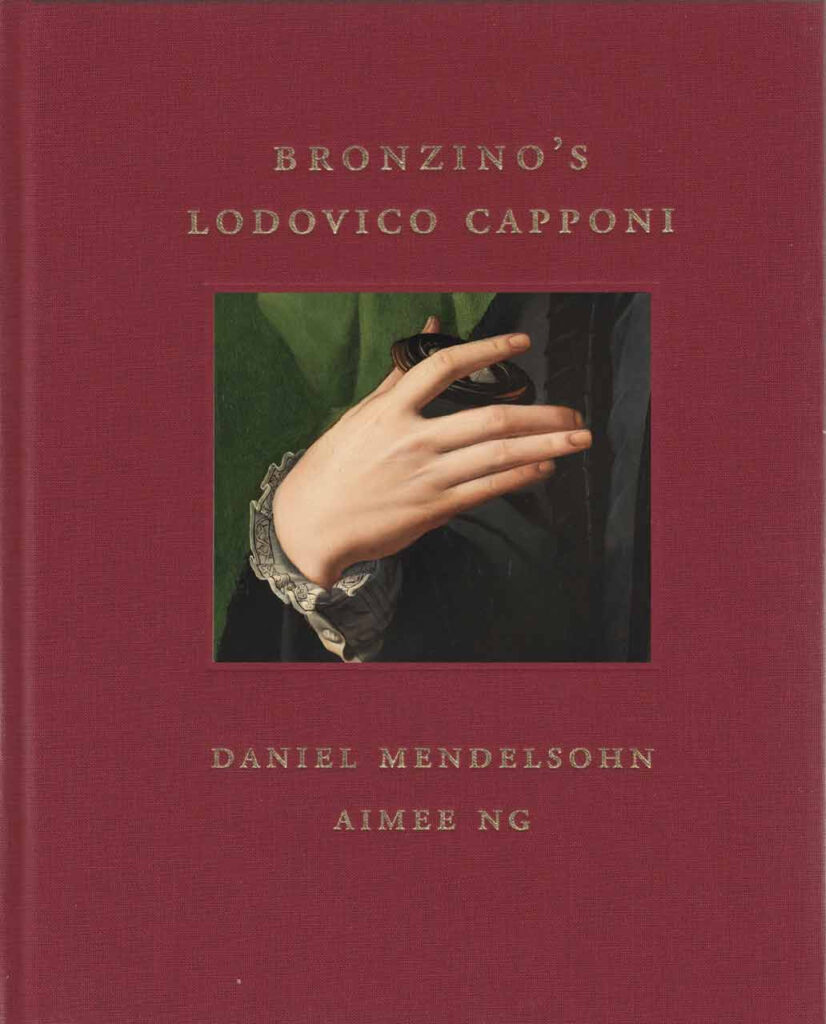

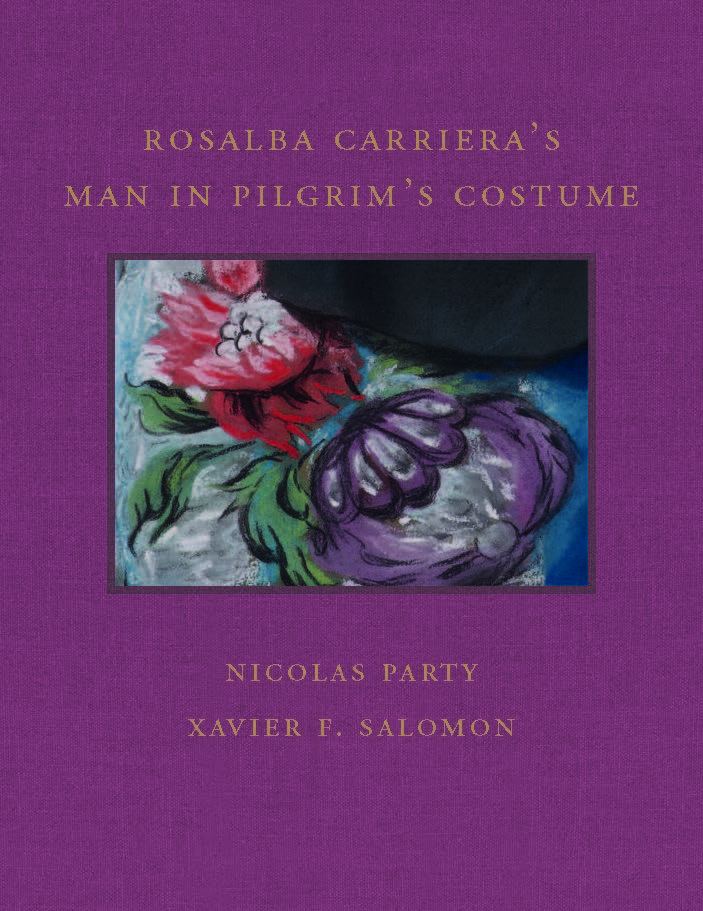

The book on Bronzino pairs the curator Aimée Ng with the essayist Daniel Mendelsohn, while the Rosalba Carriera volume brings together the curator Xavier F. Salomon and the Swiss artist Nicolas Party, who, like the eighteenth-century Carriera herself, often works in pastels. Other creative types who have contributed to previous volumes in the series include the novelists Hilary Mantel and Francine Prose, the filmmaker James Ivory, and the visual artists Maira Kalman and William Kentridge.

If the curatorial essays in this lavishly illustrated series tend to be dutiful, sober-sided, and deeply informative, the contributions from the writers and artists are highly personal responses that make no claims to objectivity. Commenting on the static, emotionless quality of the young man in Bronzino’s portrait, for example, Mendelsohn informs us that, “Perhaps because I spent a good deal of time in my twenties and thirties in gay bars and clubs, scouring the faces of self-consciously stoney-faced young men for signs of life, for some betrayal of emotion or interest, I haven’t been as willing as some to give up on the inner lives of Bronzino’s sitters.”

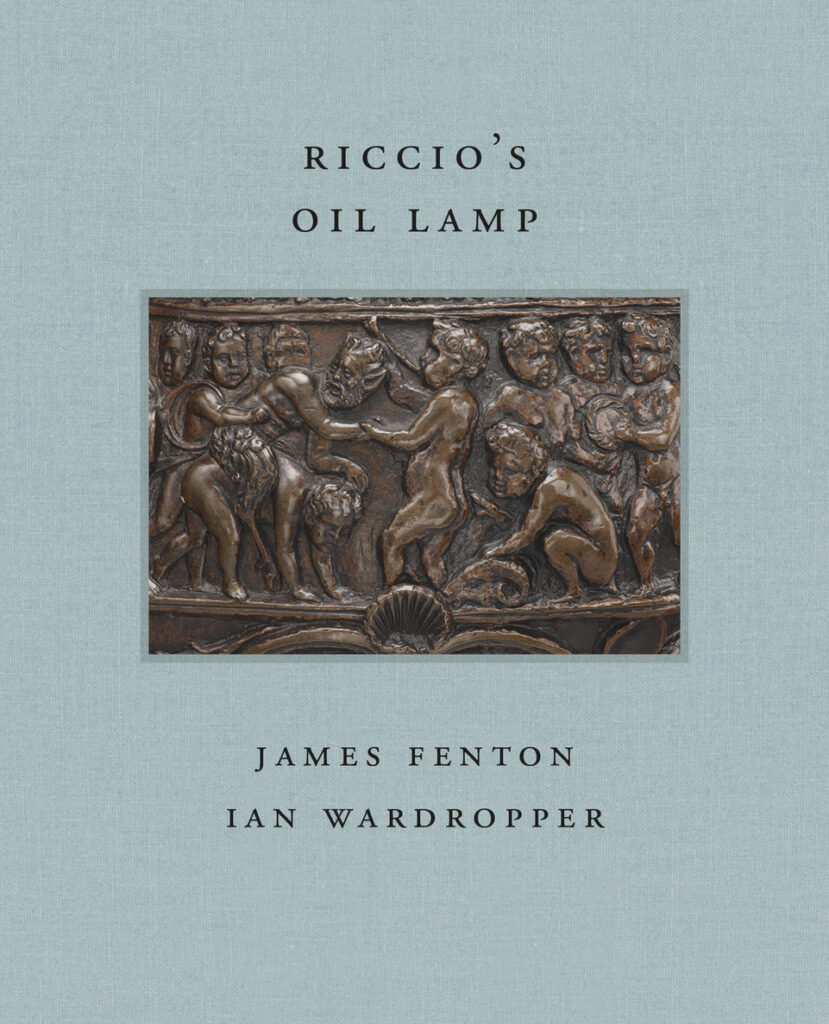

A volume devoted to Riccio’s oil lamp, which has a satyr’s head on its handle, pairs an informative essay by the Frick’s director, Ian Wardropper, with a fine poem by the British poet James Fenton, which begins with the evocative line: “A voice comes calling out of Arcady.” And before he is done, Fenton has taught at least this reader three new words, “knop,” “sprue,” and “peen,” all of which, apparently, have something to do with oil lamps.

The Frick Diptych series can be seen as part of a larger mission of the museum to shed a certain reputation for stodginess, which, in a sense is part of the job description of an institution consecrated to a collection of European antiques assembled more than a century past by an iron-willed plutocrat. In pursuit of this goal, the Frick, which will reopen next year in a much expanded version of its Fifth Avenue home, has strategically integrated examples of work by contemporary artists, like the potter Edmund de Waal as well as the painter Nicolas Party, into its displays, to form a duet, if not a diptych, between living artists and those of centuries past. The latest books in this impressive series are an example of the Frick’s growing accommodation of the present state of the world, or at least a possibly welcome acknowledgement that it exists in the first place.