Luckily for Paul Manship and his legacy, “decorative” is no longer a pejorative term in today’s pluralistic art world. The recent revival of interest in the “pattern and decoration” art movement of the 1970s and ’80s, for instance, and the renewed appreciation for craft and craftsmanship among contemporary artists, call for a reassessment of those for whom refinement, elegance, graceful forms, and decorative lines, plus astute allusions to art-historical precedents, are hallmarks of their highly polished productions. As the leading proponent of “archaism,” an international modernist movement that thrived in the first decades of the twentieth century, Manship would find many likeminded artists today, ranging from Carlo Maria Mariani and Audrey Flack to Sarah Peters and Justin Matherly, who have regularly incorporated images appropriated directly from antiquity into their works.

The sinuous lines and lithesome shapes of Manship’s highly stylized figurative sculptures, reliefs, and drawings were in vogue in the 1920s and 1930s, as his work eventually became synonymous with art deco. The postwar years saw abstract expressionism and related styles ascend, as collectors, critics, and curators favored more aggressive art forms with found materials and provocative themes. By the late 1940s, Manship’s work had been side-lined by many critics and observers as merely pleasing, and, alas, woefully decorative. These developments supplanted his art-world dominance and influence, but not his formidable achievement. One of the most beloved American sculptors of the first half of the twentieth century, Manship would naturally be due for a major reappraisal.

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, leads the way in a timely and pivotal reexamination of Manship’s accomplishments in the exhibition Paul Manship: Ancient Made Modern. Organized by the Wadsworth’s associate curator of American paintings and sculpture, Erin Monroe, the survey of some thirty-four pieces focuses on Manship’s passion for works of ancient art, and the influence they had on his modernist endeavor.

At the core of the exhibition are six Manship sculptures in the Wadsworth’s collection, supplemented by works of the artist from other institutions and private collections. Manship’s pieces are paired with ancient artworks from the Wadsworth and museum loans that complement and underscore stylistic correspondences. Although a great deal of Manship’s interests and inspirations centered on Greco-Roman antiquity, his outlook and vision had a global reach. Featured in the show is an Assyrian relief from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, now in Iraq, which shows the significant impact that ancient Middle Eastern art made on Manship early on in his career (Fig. 3).

Fig. 5. Centaur and Dryad by Manship, 1913, this cast 1925. Inscribed “To: James Robertson, 1925” on base. Bronze; height 28 1/8, width 21 1/8, depth 10 3/8 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, bequest of Honora C. Robertson.

Fig. 5a. Detail of Centaur and Dryad by Manship, 1913, this cast 1925. The detail shows satyrs cavorting with maenads. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, bequest of Honora C. Robertson.

Remarkably, the show is the first museum exhibition devoted to the artist in thirty years. His work has not been entirely invisible during that time, however. Galleries and dealers, including Gerald Peters, James Graham and Sons (now Graham Shay 1857), and Conner Rosenkranz in New York, have regularly included Manship in shows, plus several recent thematic museum exhibitions have featured his work. And all visitors to New York City can still enjoy his monumental, glittery, gilt-bronze flying Prometheus, which has graced the fountain basin at Rockefeller Center Plaza since 1934. A small bronze maquette of the statue—undoubtedly Manship’s best-known work—is among the highlights of the Wadsworth exhibition (Fig. 2).

Born and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, Manship studied at the St. Paul School of Fine Art. From there, he transferred to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in Philadelphia, before settling in New York City, where he continued his education at the Art Students League. Already a precocious and prodigious talent, in 1909 he applied for and won the prestigious Rome Prize. He resided at the American Academy in Rome from 1909 until 1912, an experience that would change his life forever.

The museums and archaeological sites of Italy sparked his lifelong fascination with the formal aspects of ancient art—its attributes of clean, crisp lines and idealized shapes, as well as the mythological themes. While based in Italy, he traveled in Greece for six weeks, and was especially enthralled by works of the Archaic period (approximately 650–480 bc) that he studied on site and in museums at Athens, Olympia, Delphi, and elsewhere. In Greece he created the intricate drawing Frieze Detail from the Treasury of Siphnians, Delphi (1912), which shows an elaborate arrangement of acanthus leaves like the kind adorning many capitals and relief sculptures from antiquity. In the exhibition, it is possible to compare the drawing with similar decorative leafy motifs on a black figure water jar (hydria), painted by Psiax about 525–510 BC.

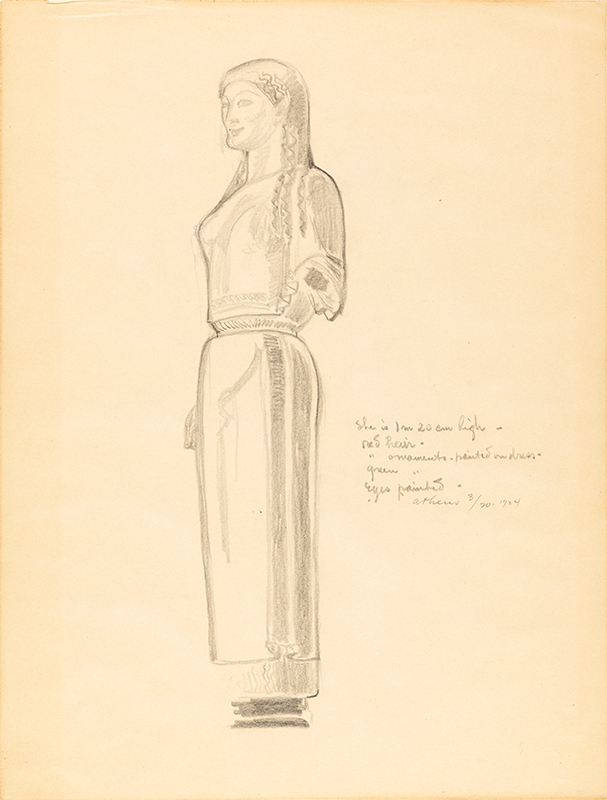

The stylistic innovations of the Archaic period, especially in kouroi and kore (sculptures of male and female youths) featuring a hint of naturalism that enlivens the otherwise schematic features and conventional forms, inspired Manship in his nascent modernist enterprise. The artist’s small bronze Lyric Muse (1912), showing a seated nude musician with her musical instrument in hand, and open mouth, as if about to sing, and a drawing, Peplos Kore from the Acropolis (Fig. 4), of a statue of a standing young woman, both directly correspond stylistically to the outlines and gently sinuous forms of the Euthydikos Kore of about 490 BC, a life-size plaster cast (bust only) of which from the Acropolis Museum is also included in the show.

Mythological themes abound in Manship’s mature works, and Ancient Made Modern contains a number of fine examples, such as Centaur and Dryad (Figs. 5, 5a), which shows the equine half-man embracing a lithe nude tree nymph in an unabashedly erotic encounter. Aside from the ancient sources, Manship may have been influenced here by the bronze Mounted Amazon (1897) by the German symbolist painter and sculptor Franz von Stuck (1863–1928). The two works share similar sleek outlines and highly stylized renderings that reflect a familiarity with Archaic-period sculptures of animals. According to Manship scholar Susan Rather, the artist likely saw Mounted Amazon at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where the work still resides.*

Classic Manship works such as the sculpture pair Diana and Actaeon (Figs. 10, 9) exemplify the sense of movement and drama the artist was able to capture with his by-now rarified visual vocabulary. Here, leaping figures appearing to fly into the air, and the hounds in pursuit, convey a hyper-energic scene by means of sleek, curving lines and ultra-high polish, like machine-age action figures.

Manship’s recurring floating-figures motif also has its source in antiquity, as in Flight of Night (Fig. 7), from the Wadsworth Atheneum’s collection. Included in the section of the exhibition titled “Modernizing Mythology,” this work shows the moon goddess Diana, nude from the waist up, and with a long flowing skirt, flying over the moon. In a series of four resplendent gilt-bronze reliefs, The Four Elements (Figs. 6a–d), commissioned for the American Telephone and Telegraph Building in New York, figures representing Earth, Air, Fire, and Water, recline or float in rhythmically swirling and undulating clouds, waves, and tongues of flame. Within the compressed spaces of these rather hypnotic compositions, Manship manages to convey at once a seemingly contradictory sense of frenzied, sensuous hedonism, and serene, meditative austerity almost in the manner of Byzantine icons. The show ends, appropriately—and wisely—with the artist’s stately bronze Great Horned Owl (Fig. 8), since the owl is the emblem of the goddess Athena.

Manship, it seems, was prescient in his omnivorous— and global—approach to image-making, in which all the diverse ancient cultures he studied and absorbed could be reimagined and realized as something fresh and new. From that perspective, and from the reassessment that the Wadsworth Atheneum presents, Manship once again proves to be one of America’s most adventurous and relevant visual thinkers.

Paul Manship: Ancient Made Modern is on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, to July 3.

DAVID EBONY is a writer and curator, a contributing editor of Art in America, and formerly its managing editor. He is the author of “David Ebony and ArtBooks,” a column for Yale University Press online, as well as numerous artists’ monographs. He lives and works in New York City.

* Susan Rather, Archaism, Modernism, and the Art of Paul Manship (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993), pp. 82–83.