The drawings of Aubrey Beardsley are, as C. Day-Lewis once said of a fellow poet, like strychnine: they are best taken in small doses. And it is a testament to their enduring power that, one and a quarter centuries after his death, they remain as potent as the day he made them, like some land mine of the Great War that can still tear your leg off. Beyond their wit and arch perfection, they possess a deep vein of irredeemable rottenness, a cynicism so toxic that it crosses over into outright misanthropy.

The occasion of the present appreciation is a show of more than two hundred Beardsley drawings and prints that opened at the Tate Britain in March and is scheduled to move—eventually, alas—to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It is the first Beardsley show at the Tate since 1923, nearly a century ago, and the largest in Europe since the one at the Victoria and Albert in 1966. The latter exhibition reintroduced Beardsley to a new generation, securing for him a reputation that prevails to this day.

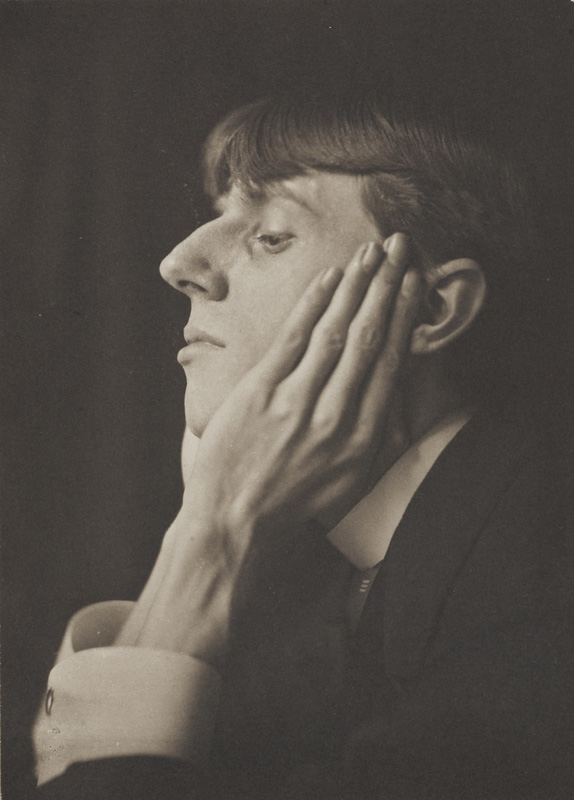

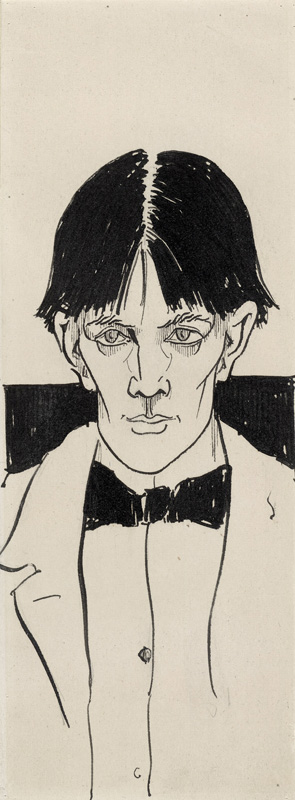

Perhaps the most notable thing about Beardsley’s life was its astounding brevity. Born in Brighton in 1872, he died of tuberculosis in his twenty-sixth year, in 1898: if Monet, or Cézanne or Renoir had died so young, we would not know their names. His grandfather, a Clerkenwell jeweler, had also died young of the same disease, and his father suffered from it throughout his life. In time, Beardsley grew into spindly and languorous adulthood, an androgynous beanpole whose spidery, tentacular fingers dominate Frederick Evans’s well-known photograph of the artist (Fig. 3). Beardsley comes off decidedly better in a self-portrait of 1892, when he was all of twenty: with his bow-tie, his mop of jet black hair and his improbably high cheekbones, he seems to possess a robustness and virility that were almost certainly fictitious (Fig. 11).

Beardsley gave himself such airs that one is surprised to learn that his family was neither prominent nor wealthy: though comfortable enough in Brighton, when his father needed to find work, they moved to modest quarters in London in the early 1880s. A bookish youth who was also quite musical, Beardsley studied at the Westminster School of Art, and before he was twenty he traveled to Paris, where, like many an English aesthete of his day, he was much influenced by Japanese prints and by the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec.

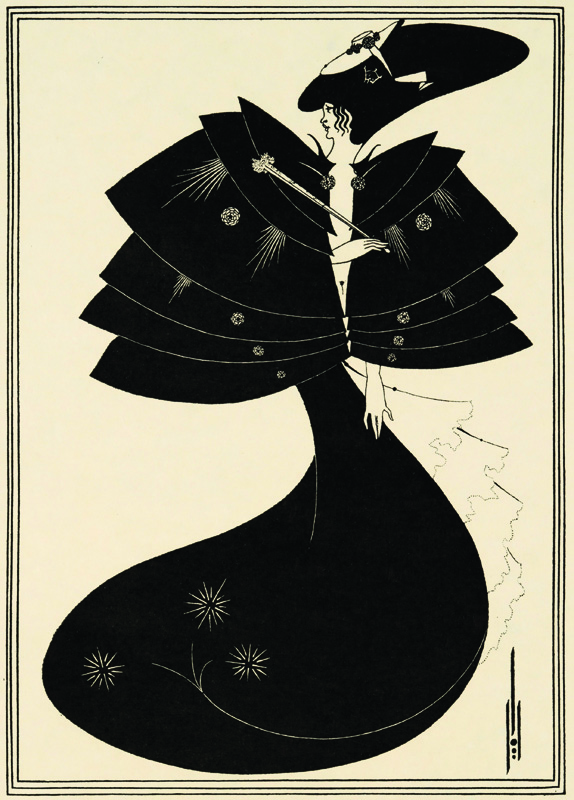

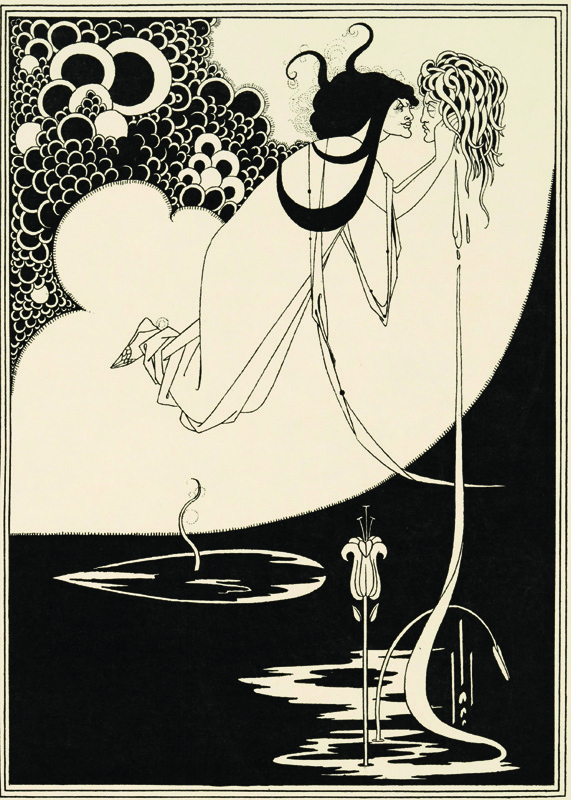

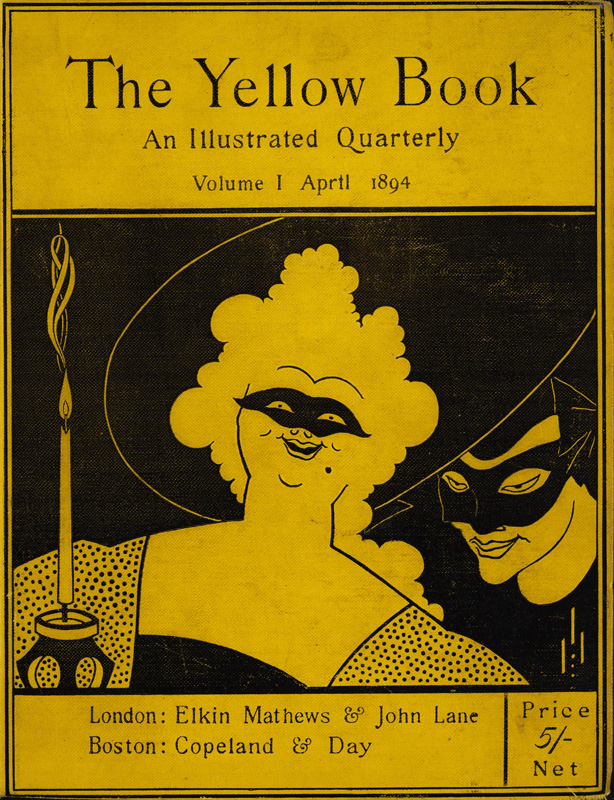

These twin sources of inspiration are vital to understanding Beardsley’s work. One hesitates to say that he was, exactly, a fine artist: his genius is that of an expert illustrator, his skills those of a graphic designer with a knack for layout. His work is almost literature by other means, as befits an artist who usually illustrated other people’s words—those of Malory, Pope, and Poe among them. His mastery of this sort of thing is evident in the graphic skill that he exhibited in laying out the Yellow Book (Fig. 5) and later the Savoy, two periodicals that he co-founded. That same infallible sense of layout, of the tension between images and large voided fields of whiteness, is evident in works like The Peacock Skirt (Fig. 4) and The Black Cape (Fig. 1). Here, however, one is more apt to be charmed by the overall structure, by the sheer technical mastery, than by any vital energy in the lines themselves: one misses that quest for formal purity that is the benchmark of the modern movement.

In this connection, it is not unfair to compare Beardsley’s lines—often little wider than a pen stroke angled across the whiteness of the page—with those of Picasso’s Ballets Russes period after 1916. In his depictions of Stravinsky and of Diaghilev, Picasso’s frail, isolated lines seek out and attain both formal beauty and experiential truth. Beardsley’s lines, by contrast—those of his self-portrait, for example—are more interested in describing reality than in abstracting its essence and reconfiguring it through the terms of his art. That is to say that the lines themselves are less important than what, in their additive accumulation, they body forth.

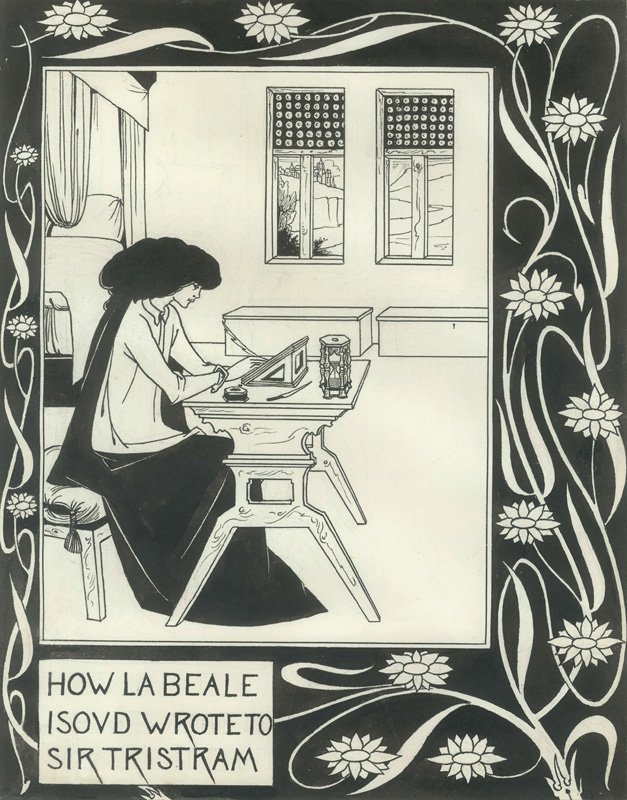

We see this difference of ambition at work in one of Beardsley’s first commissions, his illustrations to Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, for J. M. Dent and Company. They are so close in spirit to William Morris that we are surprised to learn that in fact they predated Morris’s famed Kelmscott edition of Chaucer by several years. And yet, where Morris reveals himself to be a forthright Victorian with medieval longings, Beardsley stands forth as a Francophile aesthete allied to Wilde’s last and most extravagant period, that of the play Salomé, which Beardsley illustrated. Although some of the Malory illustrations, such as The Lady of the Lake Telleth Arthur of the Sword Excalibur, exhibit a Victorian medievalism, we sense that Beardsley’s heart is not quite in them. More typical of the artist, surely, is How King Arthur Saw the Questing Beast, and thereof had great marvel (Fig. 8). Here the titular king, like all self-respecting aesthetes, looks gaunt and sickly as he contemplates the surly monster that floats before him.

Here and elsewhere, Beardsley’s muse is none other than that Imp of the Perverse that haunts the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, whom Beardsley so ably illustrated. Poe defined this creature as a force that impels us to commit—or wish to commit—shocking acts “merely because we feel we should not.” Beardsley avoids the manic cackle that rings through the works of Poe; instead, his impish muse wears a self-satisfied smirk, especially in those exercises in phallic obscenity that are his illustrations to Aristophanes’ Lysistrata and to his own licentious novella Under the Hill, a retelling of the story of Tannhäuser.

Perhaps his great single achievement is the illustrations to Pope’s Rape of the Lock. Among the most effete group of images ever contrived, they fully embody the ineffable refinement of Pope’s heroic couplets, even as they channel such eighteenth-century French illustrators as Louis Moreau the Elder. In the opening image, titled The Dream, Ariel the sylph, carrying a conjurer’s wand, stands before the bejeweled curtain of Belinda’s bed, its pure white tissue rendered in a delightfully tilted and intuitive perspective and boldly contrasted with the darkly patterned rug (Fig. 7). In this and other monuments to the artifice of terminal refinement, Beardsley created an entire universe that is autonomous and absolute in its conviction, and, in an odd way, its purity.

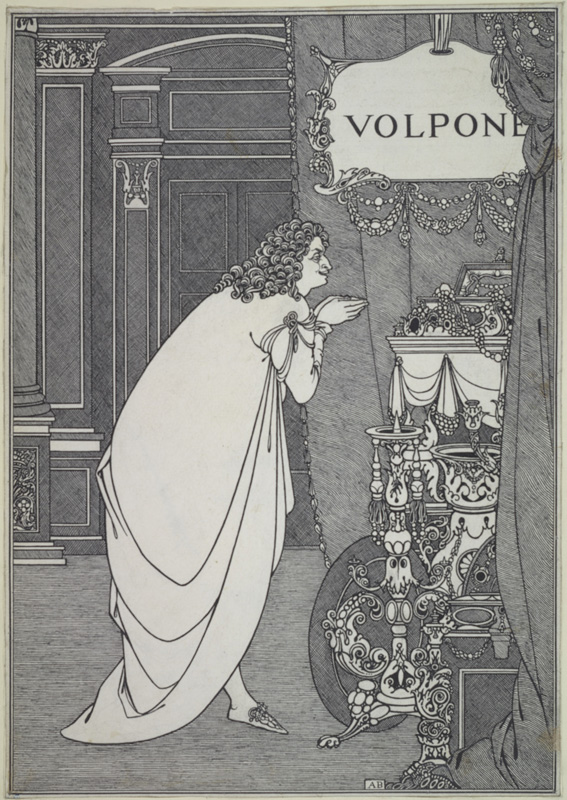

Only a year or two after completing that commission Beardsley died at an age when most artists have scarcely begun to live. And yet, one feels not only that he had had a full career, but also that it is impossible to see how he could have advanced in it. He himself appears to have suspected as much. He converted belatedly to Catholicism and in his last letter, as he lay dying of consumption in the Cosmopolitan Hotel in Menton on the French Riviera, he wrote to his publisher, Leonard Smithers, declaring that “Jesus is our Lord and Judge.” “Dear Friend,” he continued, “I implore you to destroy ALL copies of Lysistrata and bad drawings.” Fortunately for Beardsley’s legion of posthumous admirers, Smithers ignored this last request.

Aubrey Beardsley was organized by the Tate Britain in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. The exhibition was originally scheduled to remain on view at the Tate until May 25, before moving to the Paris museum on October 13. Visit tate.org.uk for updates.