The ambitious transformation of the White House by Jacqueline Kennedy (1929–1994), which began in 1961—from a hotel-like assemblage of department store reproductions to a living museum of fine American antiques—was so greatly admired that many people believed those interiors would be thenceforth immutable. But nothing at the White House is forever, as that first lady came to realize about her own work there. While I was interviewing her for a New York Times Magazine article in 1980 on White House interiors since her restoration project, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis told me with fatalistic detachment, “You know, in another hundred years it will be just one more chapter in the history of the White House.”

However, certain chapters in that two-century saga, including hers, remain more memorable than others. Another was the decorative reconception commissioned in 1882 by President Chester Alan Arthur (Fig. 2) from Louis Comfort Tiffany, which was every bit as thorough-going as Kennedy’s and yet its absolute antithesis. Even though the principal Kennedy interiors were executed by the incomparable haute monde decorator Stéphane Boudin (1888–1967) of the venerable Paris firm Maison Jansen, his client insisted this was no capricious undertaking. “It would be a sacrilege merely to redecorate—a word I hate,” Mrs. Kennedy said at the time. “It must be restored, and that has nothing to do with decoration.”1

Whatever term of art one might choose to avoid the frivolous implications of redecorating, Boudin’s historically informed approach makes Arthur’s choice of Tiffany seem amazingly daring. Arthur engaged the designer six years after the United States Centennial of 1876, which had awakened interest in our country’s estimable decorative arts heritage and the very notion of “antiques.” But such considerations played no part in a remake intended as the last word in stylish domesticity. Today Tiffany’s White House interiors (which lasted no more than twenty years) have taken on a historical aura all their own, as superlative examples of the aesthetic movement.

Apart from Presidents Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), the architect of Monticello, and Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), a patron of McKim, Mead and White, no American head of state has taken a more personal interest in White House décor than the luxury-loving Arthur, an indolent Republican party hack thrust into the nation’s highest office after the assassination of President James A. Garfield (1831–1881). Before Congress enacted a new income tax in 1913, the federal government got its revenues through import tariffs and excise taxes. There was no juicier political plum than being collector of customs for the Port of New York, the nation’s richest trade entrepôt, a post Arthur held before he became president.

The White House may be the most redecorated residence in the country, but none of its many incarnations can compare with the opulent 1882 makeover President Chester Alan Arthur commissioned from Louis Comfort Tiffany. A new series of oil paintings, published here for the first time, recaptures the brilliance of those vanished rooms.

Though no evidence proves that Arthur was on the take, he enjoyed a lavish lifestyle well above the means of a public servant. After he suddenly became president, he astonished his critics and confounded his cronies by becoming, of all things, a reformer. He supported a new civil service system that curtailed payback patronage and wrecked any hopes for his reelection. In 1882 Arthur was diagnosed with terminal Bright’s disease, which may have increased his determination to die with honor.

He may have been self-indulgent and dandified, but there was a serious political purpose behind Arthur’s decorating spree. After Garfield’s protracted deathwatch, writes historian William Seale, “The American people were exhausted by months of anxiety and sorrow. No matter what Arthur had been before, he realized that he must now inspire confidence and restore the nation’s optimism…and he believed the image he was projecting was vital to his Presidency.”2 The White House was in a state of disarray when Garfield died, only six months after his inauguration. His redecoration had barely begun.Workmen abruptly abandoned their tasks, and it took months until the disheveled rooms were habitable again. The fascinating story of Arthur’s intimate involvement with all matters of taste is a highlight of Seale’s newly published and expanded edition of his definitive two-volume 1986 study, The President’s House. He is the foremost authority on White House design, and surveys the complex evolution of the building and its interiors with unrivaled factual command and the eye of a connoisseur, and is particularly evocative in his account of the Arthur-Tiffany collaboration.

Arthur’s plans for a massive addition that would have doubled the size of the White House came to naught, and his fallback position for brand new interiors in the existing building was thwarted by the contracts Garfield had already made. Although the sophisticated new tenant deemed the local furnishers on hire hopelessly déclassé, he had to let them finish. But that did not stop him from micromanaging their activities. “Night after night,” a presidential aide recalled, Arthur “would go from room to room and corridor to corridor, giving orders to change this and that according to his own taste.”3

Apart from Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt, no American president has taken a more personal interest in White House décor than the luxury-loving Arthur.

It was no use. Arthur detested the results and ordered most of the new work ripped out and redone after a mere six months. This time there would be no Washington jobbers, or big-name firms, either. Instead, Arthur made an audacious but inspired decision when he turned to Louis Comfort Tiffany, the thirty-four-year-old son of his friend Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902), founder of the eponymous New York jewelry and luxury goods emporium.

It had been just four years since young Tiffany opened his first decorating atelier, Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated Artists, but he had completed several high-profile assignments, including work at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York in 1879 and 1880. Little is known about preliminary discussions between the ascendant designer and the knowledgeable president. Nonetheless, the results clearly indicate a shared vision of the White House as, in Seale’s phrase, “a stage for ceremonial functions.”4 This was accomplished through Tiffany’s unabashedly theatrical effects of deeply saturated color and subtly modulated gaslight. A requisite degree of magisterial display was leavened with a dash of whimsy, in counterpoint to the prevalent pomposity of Gilded Age mansions.

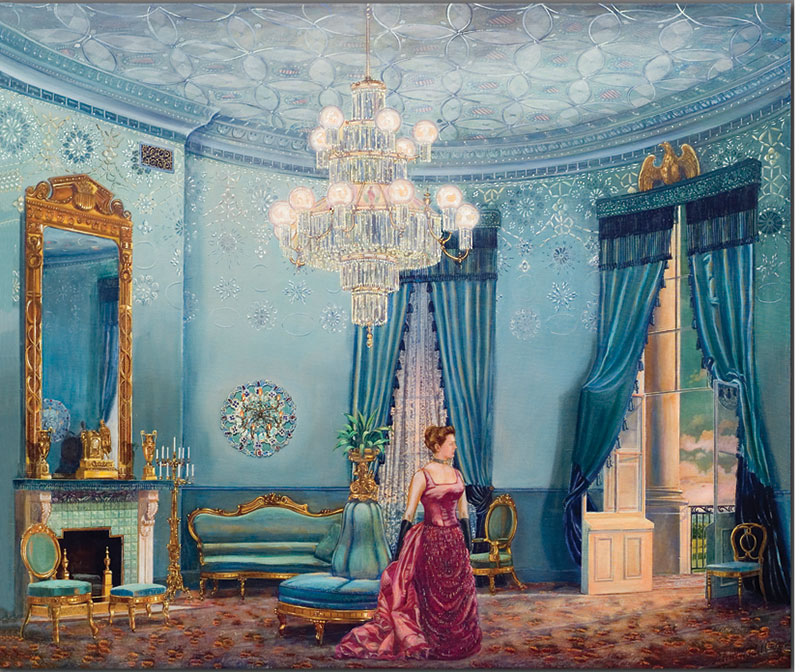

Tiffany’s inventiveness and wit were most evident in the project’s tour de force, the Blue Room, the elliptical centerpiece of the main floor (Figs. 3, 3a). Its name notwithstanding, that formal reception room has not had blue walls during much of its existence (including the past forty-six years). But because the salon’s unusual ovoid shape reminded Tiffany of a bird’s egg, he swathed it in tones of robin’s egg blue, an amusing visual pun (and a ringer for Tiffany and Company’s iconic packaging color).

An artist through and through, Tiffany was never content with routine formulas, and his wall and ceiling treatments involved complex applications of alchemical pigments, multilayered finishes, and exotic appliqués of various sorts, all to enhance his desired illusions of shimmering depth and glittering reflection. He specified that the color of the Blue Room’s curving perimeter be progressively lightened as it rose from floor to ceiling. The trio of horizontal ombré bands that encircled the space continued across the three window curtains dyed to match those gradations.

The tide of taste had begun to turn against the art nouveau aesthetic exemplified by Tiffany in 1901 when Theodore Roosevelt succeeded William McKinley.

From the 1830s onward, a favorite White House leitmotif had been a shield emblazoned with the stars and stripes. Aesthetes of the post–Civil War era disdained such nationalistic symbolism, but not Tiffany. For the ceiling of the Blue Room, he designed an allover pattern of intersecting ovals, each centered by a red, white, and blue American escutcheon. Next door, in the pompeiian-toned Red Room, the traditional stars were deconstructed, almost to the point of abstraction, and redeployed overhead in a stylized constellation of lustrous copper and gold-bronze (see Figs. 4, 4a). By the early 1880s advances in photographic technology afforded minutely detailed documentation of interiors, but as Seale observes of one monochromatic Arthur era Blue Room view, “The effect of this space is entirely lost in this black-and-white image.”5 A more vivid impression is convincingly conveyed by the artist Peter Waddell’s recent oil renderings commissioned by the White House Historical Association. Based on period photographs and descriptions of Tiffany’s palette and illumination, these welcome additions to White House iconography (vetted for accuracy by Seale) should inspire similar re-creations of other legendary lost interiors.

To avoid accusations of sumptuary excess, the president limited Tiffany’s wholesale renovations to the main floor Entry Hall, Cross Hall, East Room, Blue Room, Red Room, and State Dining Room, leaving the nearby Green Room and Family Dining Room intact. He shortsightedly auctioned off twenty-four wagon loads of White House heirlooms, many of which had survived in situ since the mansion was rebuilt to the designs of James Hoban after British invaders burned it in 1814. However, Arthur commissioned no new furniture and encouraged his designer to recycle many remaining pieces, which were so well integrated into the new decor that everything appeared custom-made.

Tiffany’s most celebrated component was his polychrome leaded-glass screen for the Entry Hall, behind the pedimented portico facing Pennsylvania Avenue (see Figs. 1, 1a). The mansion’s front door is now used mainly on major occasions, but before office wings were added to the White House in the early twentieth century, the main floor could be insufferably drafty. To remedy that problem, in 1837 President Martin Van Buren (1782–1862) had a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling glass-paned partition installed within the triple archways linking the Entry Hall with the principal public rooms. In 1853 under President Franklin Pierce (1804–1869), the architect Thomas Ustick Walter replaced that wind barrier with a more substantial screen of cast iron and glass. Tiffany retained Walter’s metal framework, but substituted his own panels of translucent red, white, and blue glass to a height of about ten feet, with colorless clerestories above (see Fig. 1).

The tide of taste had begun to turn against the aesthetic movement exemplified by Tiffany in 1901 when Theodore Roosevelt succeeded William McKinley (1843–1901), who was gunned down like Garfield. Roosevelt abhorred Victorian clutter, and called in McKim, Mead and White to revamp the White House in the increasingly fashionable colonial revival style. Tiffany’s glazed foyer partition was dismantled in 1902, sent to auction, bought by a Maryland resort proprietor, and presumably destroyed when the hotel burned down in 1923.

Now we can only imagine the magical aura cast by Tiffany’s screen. “The stained-glass mosaic made the long hall continually iridescent,” Seale writes in The President’s House. “The colors did not replicate the red, white, and blue of the flag, yet carried the theme with splashes of crimson, cobalt, and white, blue-white, rosy-white, and amber-white.”6 It was the perfect backdrop for Arthur, a real-life Yankee Doodle dandy.

1 Quoted in Hugh Sidey, “The First Lady Brings History and Beauty to the White House,” Life, September 1, 1961, p. 62. 2 William Seale, The President’s House (White House Historical Association with the cooperation of the National Geographic Society, Washington, D. C., 1986), vol. 1, p. 531. 3 Ibid., p. 514. 4 Ibid, p. 542. 5 Seale, The White House: The History of an American Idea (White House Historical Association, Washington, D. C., 1992), p. 140. 6 Seale, The President’s House, vol. 1, p. 543.

MARTIN FILLER is a regular contributor to Antiques.