For much of human history, people were forced to imagine what the moon was really like. Was it flat like a disk? Made of cheese? Was it inhabited? Photography answered those questions and more, allowing earthbound observers to unlock the moon’s secrets in the lead-up to visiting it in person on July 20, 1969. Three exhibitions this year—at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York—dig into the history of lunar photography.

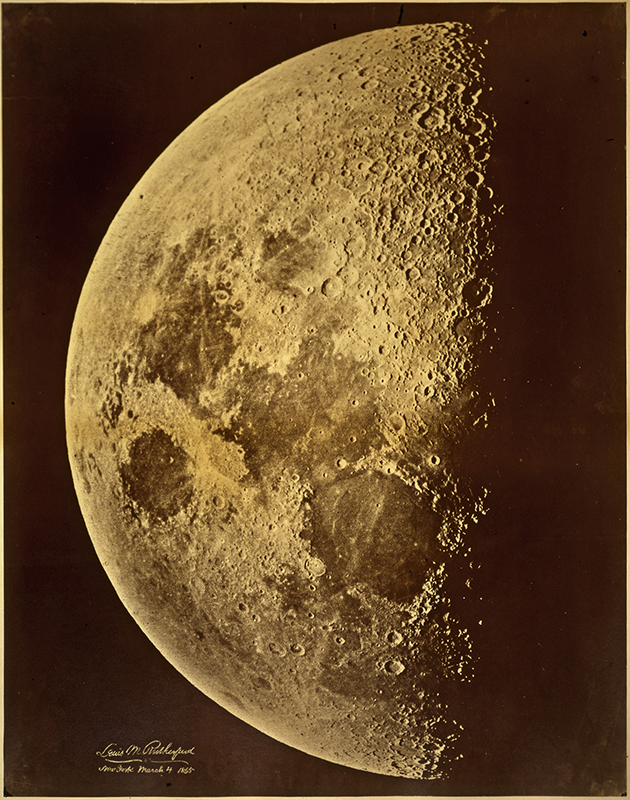

Of course, the history of moon-mapping, or selenography, doesn’t begin with the advent of photography. When physicist and astronomer François Arago described the daguerreotype process to the French Academy of Sciences in 1839, more than two hundred years had already elapsed since Galileo Galilei trained his telescope on the moon and discovered it wasn’t perfectly smooth but pockmarked and scratched, patchily discolored by “seas” spreading across its surface. Galileo recorded his observations in drawings—on view at the Met—and for centuries, astronomers improved on them with the aid of increasingly powerful telescopes. But science demanded more, and photography offered a faster, more detailed, and more faithful way to picture the moon . . . in theory. In fact, photography was beset by a number of problems that limited its utility for selenographers. The first was that the relative insensitivity of the daguerreotype’s iodine-salted-silver substrate necessitated long exposures—hardly ideal for photographing a tiny point of light moving across the night sky. Early attempts at photographing the moon, like Samuel Dwight Humphrey’s Multiple Exposures of the Moon: Nine Exposures Ranging from Two Minutes to Half a Second from 1849, succeeded only in fixing smudges of light—sublime, but hardly scientifically useful. But there was no obstacle an army of amateur astronomers and photographers couldn’t surmount. After the development of the wet-plate collodion process in 1851 significantly reduced exposure times, in 1856 Liverpudlian Warren De La Rue devised a driving mechanism for his telescope, allowing it to track the moon as it moved. By the time the Civil War was winding down, the development of an achromatic lens by American enthusiast Lewis Morris Rutherfurd meant that the first truly mind-blowingly detailed images of the moon could be made.

But for all these terrestrial advances, the key to getting good pictures of the moon turned out to be a matter of simply getting closer. In the 1950s Soviet and US lunar modules took off on the 250,000-mile journey from our earth to the moon. A robotic imaging system mounted aboard the Lunar Orbiter spaceships in 1966 and 1967—designed by Eastman Kodak—allowed NASA to map the rilles and craters of potential landing sites for the lunar lander in incredible detail. Though NASA technicians at first objected to Apollo 11’s astronauts carrying heavy personal cameras, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins insisted, and in 1969 they shot the most famous of all pictures of our celestial companion, up close and personal.

Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography • Metropolitan Museum of Art • to September 22 • metmuseum.org.

By the Light of the Silvery Moon: A Century of Lunar Photographs • National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC • to January 5, 2020 • naga.gov

A History of Photography • George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York • to October 20 • eastman.org