During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Cleveland, Ohio, was home to more than a hundred different automobile companies and rivaled Detroit as a car-manufacturing center. Most Cleveland cars were luxury cars, produced in relatively small numbers, and were not competitive in price once Henry Ford introduced autos made on the continuous assembly line. By the early 1930s, after the stock market crashed, the market for luxury cars largely disappeared, and all the Cleveland automotive companies folded, with the exception of White Trucks, which sputtered on for a few more decades.1

For all that, tracing the history of these Cleveland cars provides a remarkable record of the evolution of the automobile, in just a few decades, from an uncomfortable, unenclosed, purely utilitarian machine, to an object of glamor associated with a luxury lifestyle and a new level of individual freedom and mobility. Of these creations, perhaps the most remarkable was the Jordan Playboy, which, despite its name, was the first car with a marketing campaign directed not only to men, but, very explicitly, to the liberated woman as well. The fascinating story of the Playboy will be the subject of a forthcoming exhibition at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, the city’s oldest cultural organization.

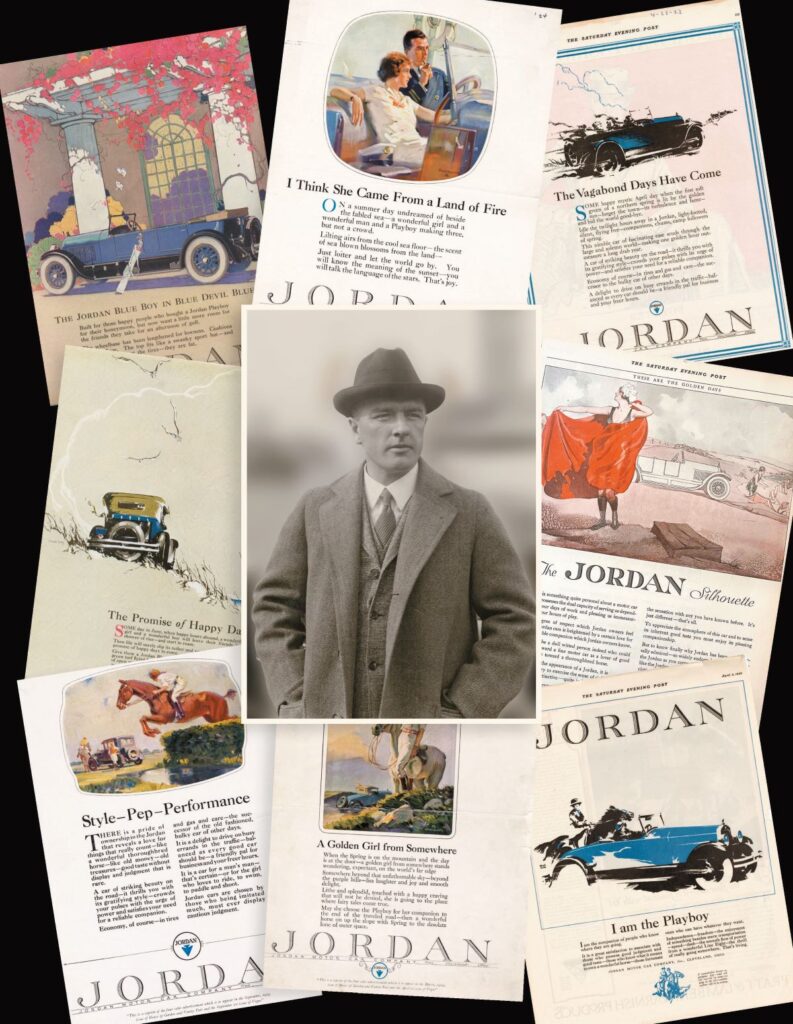

Edward S. “Ned” Jordan, who created the Jordan Motor Car Company, was an upstart in the automotive business (Fig. 2). His background was not in manufacturing or engineering but in journalism. From 1907 to 1916, however, he served as sales manager for the Jeffery Company, in Kenosha, Wisconsin, which in 1902 had turned from manufacturing bicycles to building automobiles. In 1916, just before the Jeffery Company was sold to another local automaker, Nash Motors, Jordan resigned and announced that he planned to create an automobile company of his own. What he envisaged was not a mass-production car but a high-quality machine, which would sell just below the most expensive automobiles, in a niche just above Buick but below Cadillac. Manufacturing began in June of 1916, and the car was announced to the public on September 2, with an expensive full-page ad in the Saturday Evening Post.2

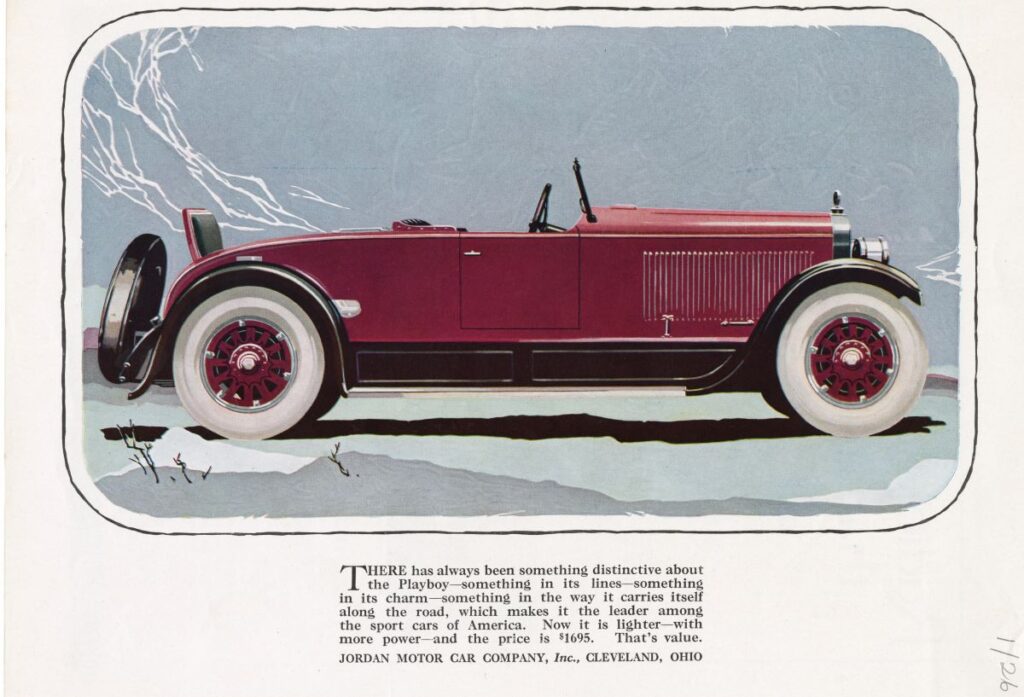

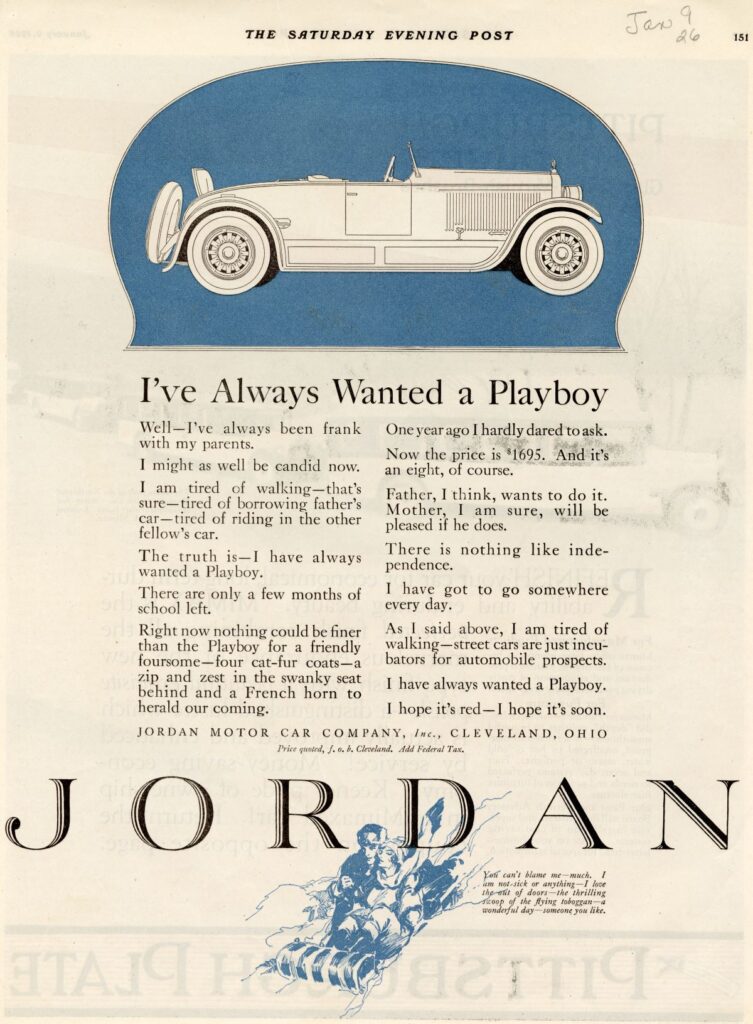

From the standpoint of engineering and mechanics, little about the car was pioneering. What was original was the emphasis on style and luxury at a reasonably affordable price point, which ranged from about $1,000 to $3,000. The concept for his best-remembered car, the Playboy (Fig. 5),came to Jordan in 1918, when he was dancing with an attractive young woman named Eleanor Borton, age nineteen. In Jordan’s telling, she said to him: “Mr. Jordan, why don’t you build a car for the girl who likes to swim, paddle, and shoot, and for the boy who loves the roar of a cut out.”3

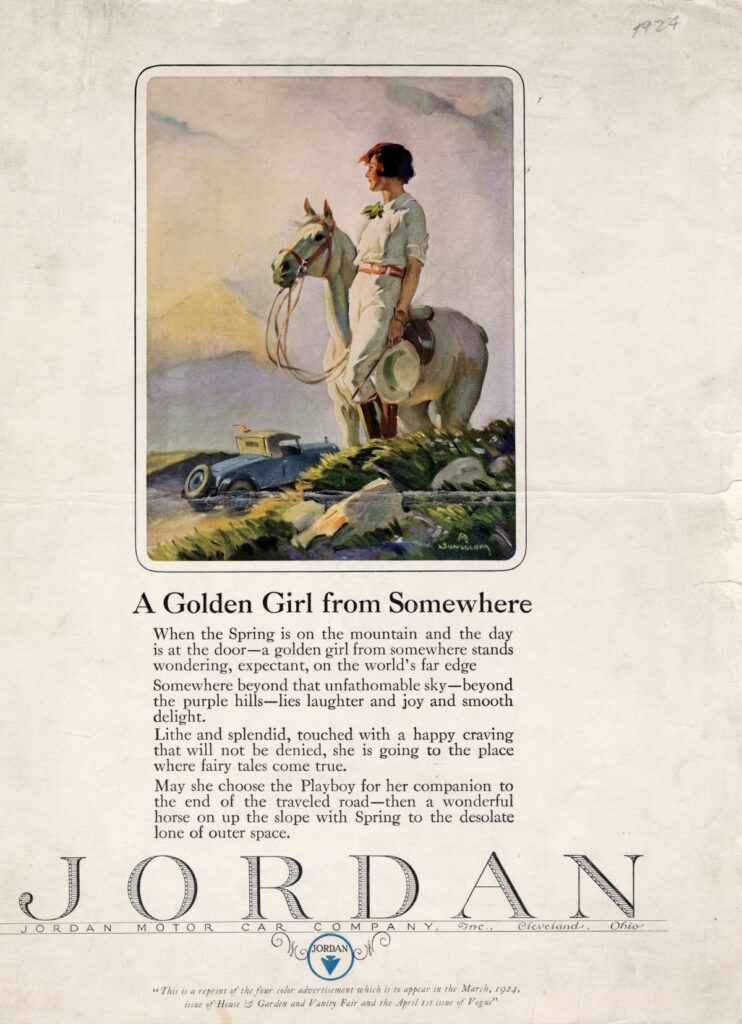

Jordan realized that a new type of woman was emerging in America—one who was discarding the corseted restraints of the Victorian era and was becoming more adventurous and athletic. Not least, one interested in mobility and freedom—including freedom from archaic sexual mores. With a car of her own, a woman who had been imprisoned at home could suddenly venture out more widely to socialize, to have fun, to romance, or even to pursue a career.

Jordan had originally considered naming the car the Doughboy, in honor of the soldiers who were returning from France, but this surely sounded too soft and dumpy, and he settled instead on the name Playboy, which sounded more glamorous and also, perhaps, a little bit racy. The word “playboy” was used in the eighteenth century for a boy who performed in the theater, and in the nineteenth century took on connotations of a gambler, or musician, or of someone well supplied with money out to enjoy himself. Jordan later claimed that he was inspired by the Irish writer John Millington Synge’s play The Playboy of the Western World, which had stirred up conversation a few years earlier. Jordan’s car surely contributed to the popularity of the word, as well as to its risqué connotations, which were firmly established a generation later by Hugh Hefner’s hugely successful magazine.

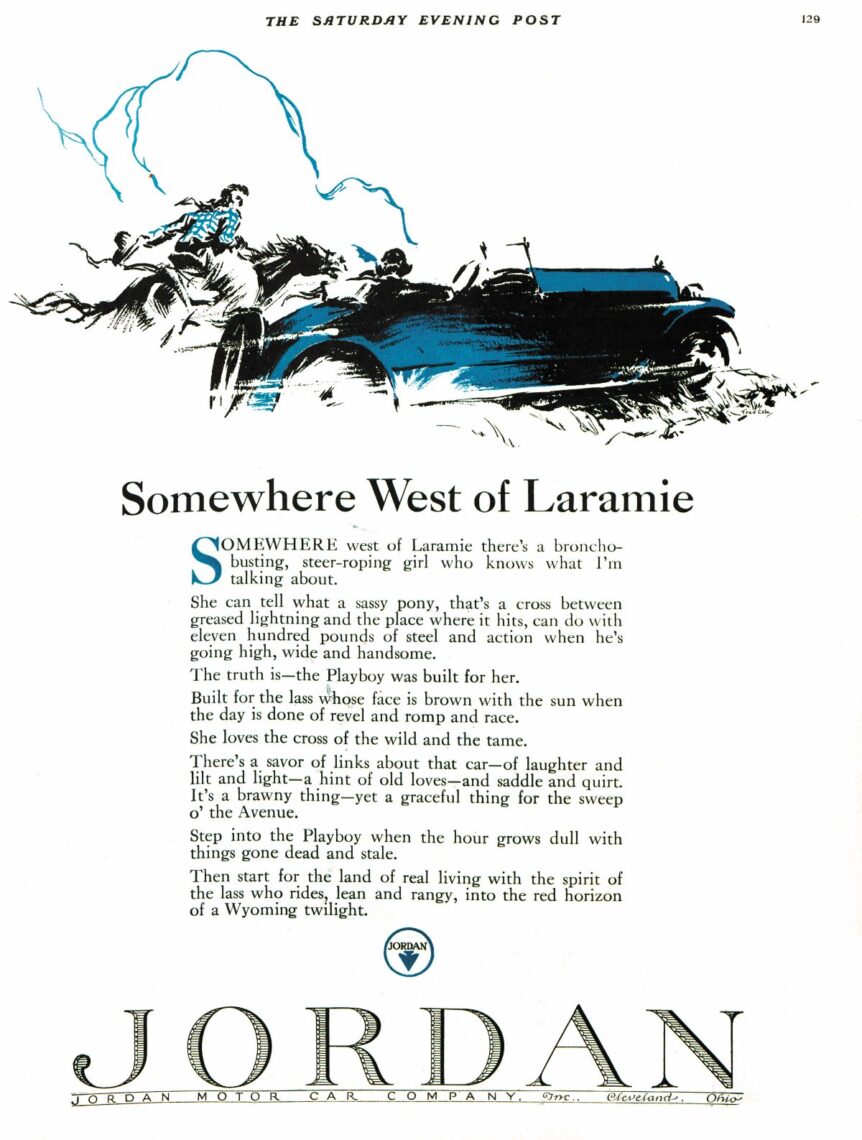

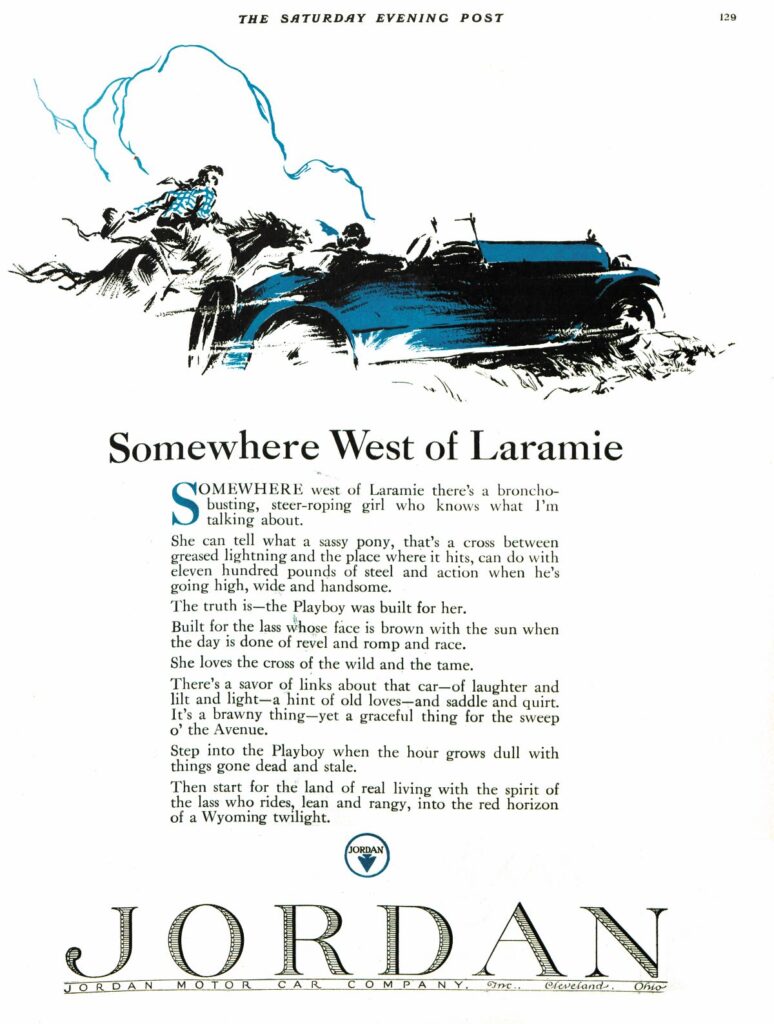

But Jordan’s concept from the first was to create a car that would appeal not just to the lusty playboys of the Jazz Age, but to adventuresome women as well. On June 23, 1923, he ran another ad in the Saturday Evening Post that transformed the way automobiles were marketed ever after (Fig. 1).

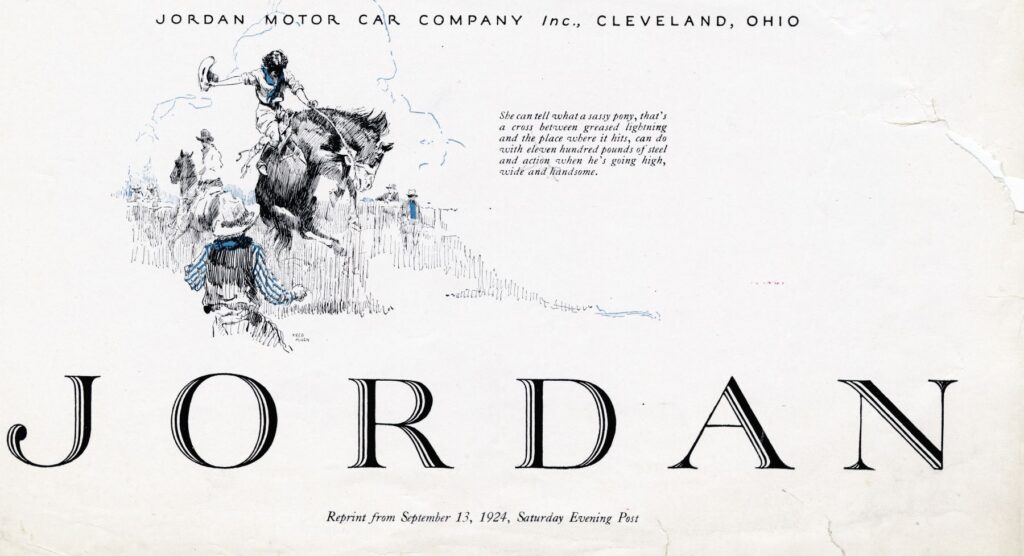

The illustration for the ad showed a cowboy on horseback racing a woman in a cloche hat driving a deep blue Playboy. Jordan later recalled that the ad originated when he was on a train going through Wyoming, headed to California, and spotted a young woman on a pony racing the train. Turning to his companion, an attorney who was accompanying him, he asked where they were. He replied: “Somewhere west of Laramie.” Jordan promptly jotted down sixty-five words that changed advertising history. The text went as follows:

Somewhere West of Laramie

Somewhere west of Laramie there’s a broncho-busting, steer-roping girl who knows what I’m talking about. She can tell what a sassy pony, that’s a cross between greased lightning and the place where it hits can do with eleven hundred pounds of steel and action, when he’s going high, wide and handsome. The truth is—the Jordan Playboy was built for her. 4

The text in that June 23 advertisement continues, but in subsequent versions only the words quoted above appear. The images vary in later iterations of the ad, sometimes showing a woman, sometimes a man, as the rider of the horse or the driver of the car.

The mode of diction in the advertisement is more like poetry than ordinary prose, and in fact it takes careful re-reading to figure out exactly what Jordan is saying, although the underlying message is clear. “Somewhere west of Laramie” has the quality of a fairy-tale, and evokes the exotic, distant West of movies and novels—the land of manly riders of the purple sage, the escapist dreamland of American city dwellers. This was the decade when novels by Zane Gray topped the best-seller list year after year. While it’s the man who is shown riding a horse, if you read carefully the text seems to also describe the car the woman drives as a “sassy pony,” and presumably she knows how to ride horses as well. Like the man, she’s surely sunburned and athletic, qualities of the sort of young woman for whom the Jordan was created, which were brought out more explicitly in later advertisements.

“Greased lightning” and “the place where it hits” capture the popular idioms of the time, and give the writing a youthful flavor. Clearly this is a car for the young and the adventurous in tune with such banter. Interestingly, there’s a bit of ambiguity over who should be driving the car. It’s a man who’s “going high, wide and handsome.” But, significantly, the Jordan Playboy “was built for her.”

Jordan’s blurring of references and meanings has an interesting affinity with the innovations of experimental, modernist writers of the time, such as James Joyce. In an ingenious way, Jordan plays on the male’s inner need to be manly, and to attract beautiful women with his strength and power, as driver of the car, and the woman’s need to assume the sort of power that at the time was mostly the prerogative of the male. While the man is clearly powerful and handsome, and master of “eleven hundred pounds of steel and action,” the woman is the one “who knows what I’m talking about,” and she’s the one the Jordan was built to please. In short, this is a car that enables a woman to become independent and liberated—to escape from the confining walls of the home, the traditional female sphere—and to become footloose and fancy free.

Notably, the ad says nothing about the reliability or the engineering of the machine, and in the illustration the car is just a featureless blur, whose specific make is not discernable. The power of the sales pitch lies in its appeal to the unconscious, and to deep-rooted sexual drives of the sort then gradually gaining a hold on public awareness through the writings of Sigmund Freud.

The popularity of the ad is suggested by the fact that, not long after it appeared, a parody was published in Playboy—an art and satire magazine published intermittently in New York between 1919 and 1923. This ran:

ARTLESS ADS

By the Office Boy

Somewhere West of Lankershim

Somewhere west of Lankershim there’s a high-stepping, devil-may-care girl who knows what I’m talking about. She knows what happens when the “gas” runs out when she’s miles out of town with a fellow who’s running high, wide and handsome.

The fact is our roller skates were made for her.

MORON

ROLLER SKATES 5

While the humor is distinctly feeble, the parody points out the way Jordan’s ad plays with issues that were a source of interest to young people at the time—including new, liberating activities for women. Like driving cars, roller skating was one of the first athletic activities considered appropriate for women and was a sport that came into vogue in America right around the turn of the century.

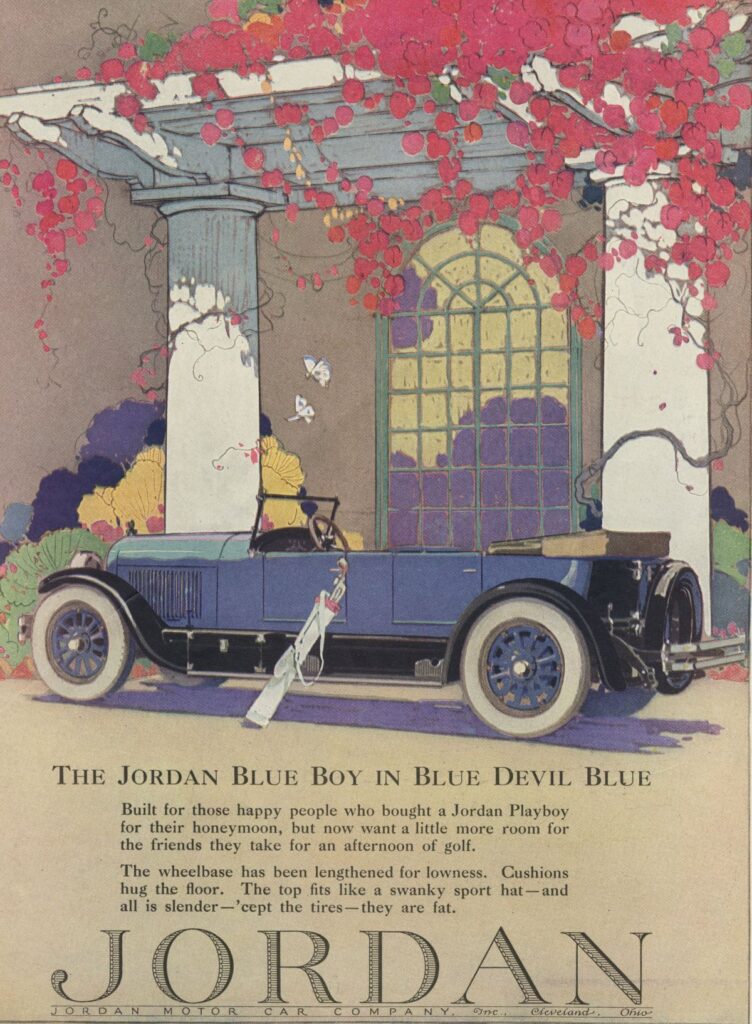

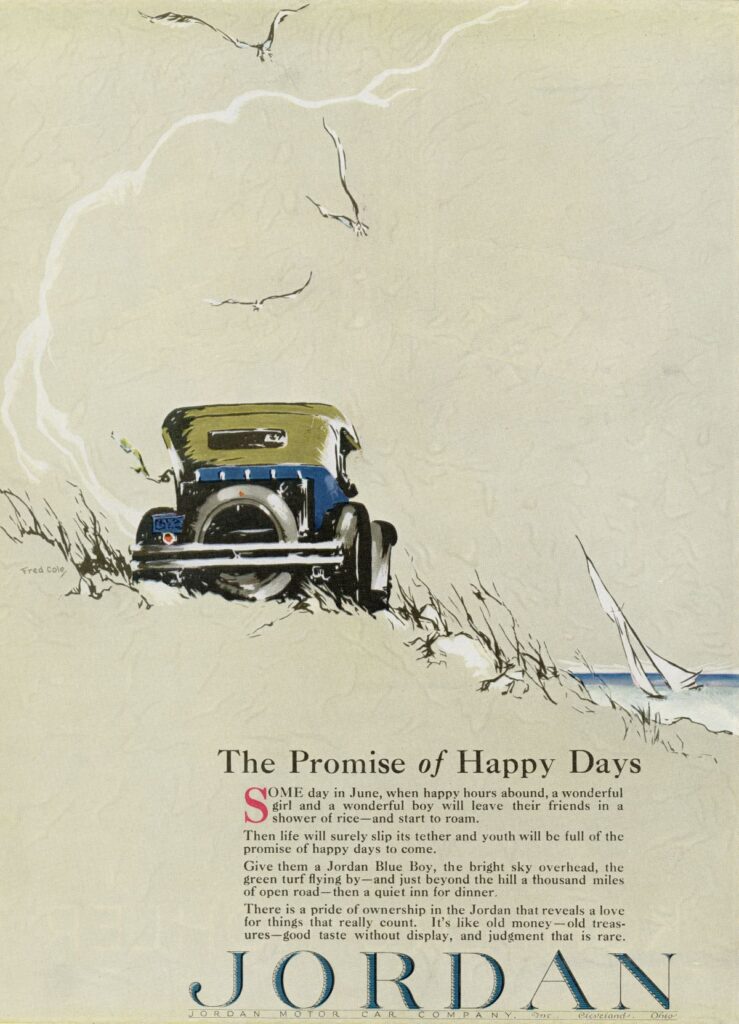

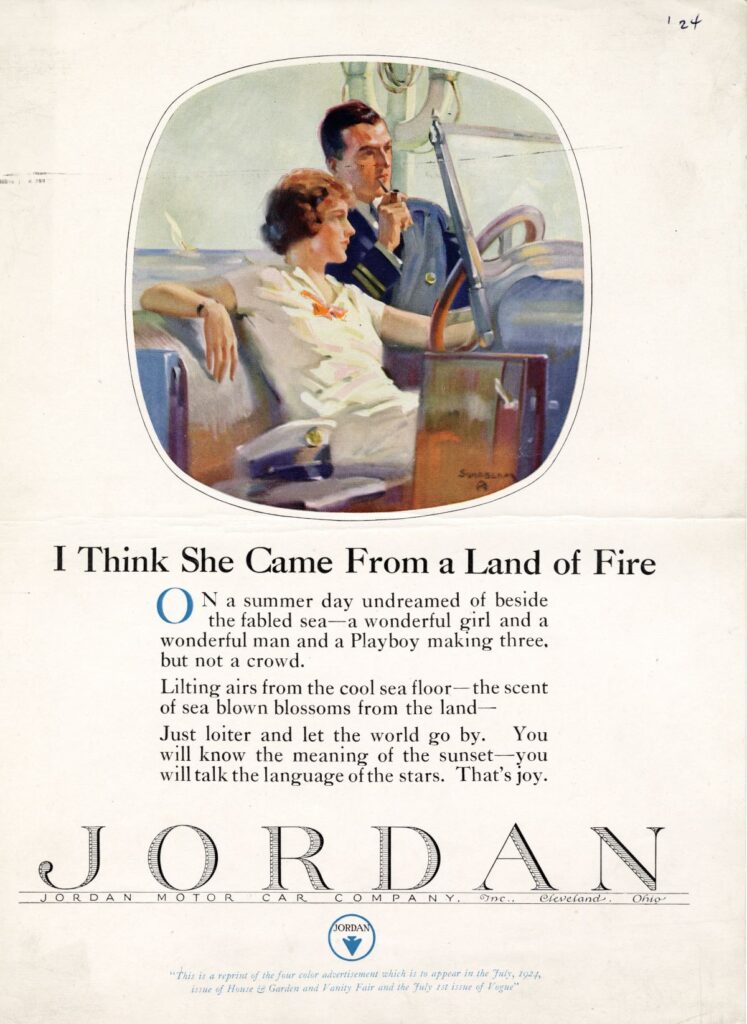

From the first, Jordan clearly intended his car for an audience that was well-heeled, essentially the country club set—recognizing that Henry Ford had already cornered the lower end of the market. Once he had perfected his pitch, Jordan generally ran ads that were in color and full-page, in magazines that carried an aura of financial comfort and social prestige. Their artwork often featured emblems of affluence, such as golf courses, swimming pools, and columned houses.

Jordan carefully targeted his audience. Aside from regional advertisements, the ads for the Playboy were run in magazines that he chose for their appeal to an upscale, educated, and fashion-minded audience, among them the Saturday Evening Post, a fixture in affluent, respectable households in this period; Vanity Fair, House and Garden, and Vogue, all published by Condé Nast (Figs. 7, 9, 12, 13); and Life, a humor magazine before it was purchased and reformatted in 1936 by Henry Luce of Time Inc.

Color was one of the things that made the Playboy stand out. At the time Ford offered only black. The Playboy came in a variety of colors, and Jordan was the first to give colors poetic names such as Apache Red, Ocean Sand Gray, Italian Tan, Egyptian Bronze, Apple Blossom Green, Chinese Blue, Venetian Green, and Savage Red—a marketing strategy later picked up by paint companies as well. Through this device, color became an indicator of the exciting qualities of the machine. Indeed, if you purchased a car painted “Blue Devil Blue” (Fig. 4), this surely established that you were a bit of an adventurous devil yourself.

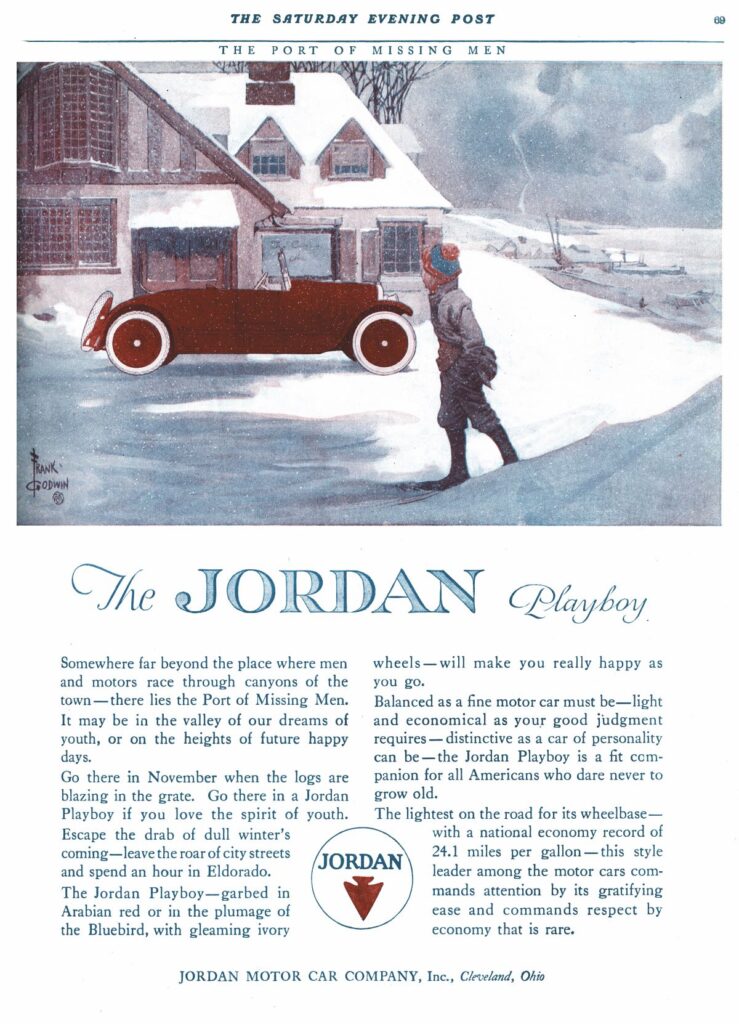

Notably, Jordan’s ads also contained an element of sexual innuendo that was unprecedented for the period, and repeatedly played on the themes of amorous adventure, romance, and sex. For example, an ad of 1920 titled “The Port of Missing Men,” which ran in the Literary Digest, the Saturday Evening Post, and Country Gentleman, featured a red Playboy parked in front of a seaside establishment, with dim light coming from an upstairs window, implying that the couple who owned the car were probably in bed together (Fig. 6). Shortly after the ad appeared, Jordan received a scathing letter from the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, founded by Anthony Comstock, admonishing him to refrain from ever publishing something so salacious again. In response, Jordan wrote a contrite letter of apology, but was no doubt secretly pleased that the ad had hit a nerve, just as he intended.6

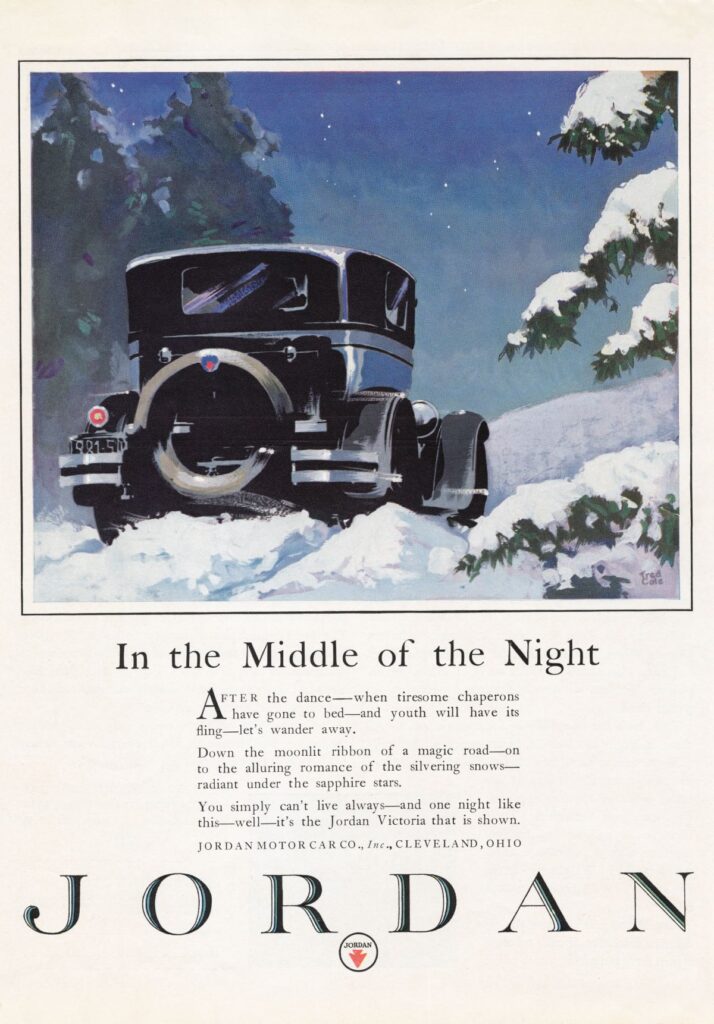

In the January 1927 issue of House and Garden, Jordan once again ran an ad that provoked the ire of the Society for the Suppression of Vice in New York (Fig. 9). Headlined “In the Middle of the Night,” this advertisement cheerfully declared:

After the dance—when the tiresome

chaperons have gone to bed—and youth

will have its fling—let’s wander away.

Down the moonlit ribbon of a magic road—

onto the alluring

romance of the silvery snows—

radiant under the sapphire stars.

You simply can’t live always—and

one night like this—well—it’s the

Jordan Victoria that is shown.

John S. Summer, secretary of the society, was quick to pick up on the innuendo, and wrote to the Jordan’s advertising department detailing why the ad was offensive. The car wasn’t moving—it had stopped—and no people were visible, very likely because they are horizontal, and thus lower than the windows. In other words, they were probably petting or—God forbid!—perhaps even engaging in sexual intercourse in the back seat. That the latter conjecture might be accurate is suggested by the gentle hint in Jordan’s text that this is a night worth remembering for a lifetime.7

In short, Jordan was the pioneer of the concept that sex appeal could sell cars. And he demonstrated that the method works. The company had its most profitable years in the mid-1920s, when its annual profits came close to a million dollars, of which Jordan himself pocketed a considerable share. Unfortunately, however, as Ford cars dropped significantly in price, and as General Motors grew more powerful, and focused increasingly on style, the Jordan Motor Car Company began a steady descent toward ultimate bankruptcy. In 1926 the company produced more cars than it could sell, and in 1927, due to five-month delays in delivering the new model, its sales diminished further. In 1928 Ned Jordan lost control of the company, and the financial crash of October 1929 hastened what was already a death spiral.

New models were announced in 1930, the most lavish of which was the Model Z, perhaps the most luxurious car that Jordan ever made. Only fourteen examples were produced, just one of which still survives. But by this time the clock was running out on the firm. On May 8, 1931, the company entered into bankruptcy, and its plant and assets were sold off at a tremendous loss. The company’s creditors received only 15 cents on the dollar of their claims.

Once wealthy, with a grand mansion, and making frequent contributions to charity events, Jordan became essentially destitute. His fall from riches to rags seems worthy of a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald. After his car company’s collapse, he supported himself by working in advertising firms and spent his final years living in cheap hotels in various parts of New York City. After a series of strokes, he died in a welfare hospital in New York on December 30, 1958. Today, most Americans have never heard of Ned Jordan or of the Jordan Playboy, although it surely deserves to be more widely known. The ways in which it opened up a new lifestyle for women, and transformed the marketing of cars, and indeed advertising more generally, still resonate today.

For help with this article, I’d like to particularly thank Bradley Brownell, director of the Crawford Automotive Museum of the Western Reserve Historical Society; John Lutsch, program and marketing manager at the Crawford; Ann Sindelar, reference supervisor at the Western Reserve Historical Society; and John and Peggy Willi, respectively, director and treasurer of the Jordan Register, a group that celebrates Jordan cars.

The Jordan Playboy: A Car for the Liberated Woman will be on view at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland from April 15 to September 30.

1 For a survey of all the different makes of automobile produced in Cleveland, see Richard Wager, Golden Wheels: The Story of the Automobiles Made in Cleveland and Northeastern Ohio, 1892–1932 (Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society and John T. Zubal, Inc., 1986). 2 The most comprehensive account of the Jordan Playboy is James H. Lackey, The Jordan Automobile: A History (Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland and Company, 2005). See also Rick Taylor, “Somewhere West of Laramie: 1928 Jordan Playboy,” Special Interest Autos, no. 31 (November/December 1975), pp. 12–17, 20–22, 52; Tim Howley, “When the Jordan Rolled, Antique Automobile, March 1966, pp. 5–20; Richard M. Langworth, “Ned Jordan: The Cars He Built,” Automobile Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 2 (1975), pp. 168–181; Karl S. Zahm, “Jordan: Flash Cars and Flashy Prose,”Cars and Parts, September 1982, pp. 26–28; Karl S. Zahm, “Jordan: The Final Years,”Cars and Parts, October 1982, pp. 50–53. 3 Edward S. [Ned] Jordan, The Inside Story of Adam and Eve (Utica, NY: Howard Coggeshall, 1945), pp.14–16; Jordan told the story again in his article “With Ned Jordan” in Automotive News, May 28, 1951, p. 10. 4 For more about the ad, see Jordan, The Inside Story of Adam and Eve, pp. 80–81. 5 The ad is illustrated in Lackey, The Jordan Automobile, p. 54. 6 Ibid., p. 40. 7 Ibid., pp. 76–77.

HENRY ADAMS, the Ruth Coulter Heede professor of art history at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, is the curator of The Jordan Playboy: A Car for the Liberated Woman.