Americans, it might be observed, are once again living in proverbial “interesting times.” It’s a natural human impulse to try to untangle the historical roots of such moments, and that is half the program of A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845, an exhibition of more than 170 vintage and contemporary works at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the first major survey of southern photography in more than twenty-five years.

In images such as Rebel Works in Front of Atlanta, Ga., No. 1 (1864) by the Mathew Brady associate G. N. Barnard, Charles Moore’s decisively captured Martin Luther King Jr. Arrested, Montgomery, Alabama (1958), and High School Students after Black Lives Matter Protest, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C. by An-My Lê, to cite but a few, viewers can trace that most axiomatic of arcs as it bends, if not toward justice, in the direction of some sort of change. That same grouping may also be used to teach a history of the medium, from its early use as a tool of reportage, to photographers’ embrace of straight photography—which melded sharp focus and unfussy surfaces with a mandate to depict the social world as it is—until ending up, apparently, at a place between the two.

Examined from yet another angle, those three images chart photographers’ progressive realization that their medium is more like painting than contact printing. The crudity of Barnard’s vista, with its overexposed and tightly compressed ground, clogged with overlapping particulars, speaks volumes about the faith his era placed in the camera. To make more effective pictures, photographers had to learn how to coax the world into volubility, using framing, contrast, perspective—even choreography. In other works from her ongoing Silent General series (of which High School Students forms a part), Lê has used a TV stage-set Oval Office; paid actors to impersonate soldiers in Iraq; and pulled the camera out wide from a Civil War re-enactment to reveal grips, boom man, and scrim. Such images make photography’s constructedness their subject, but it’s when Lê unabashedly uses the tools at her disposal that she begins, so to speak, to paint. Ostensibly a candid shot, High School Students is made strange by the curious, aestheticized posture of the seated figures. Follow the sight lines of all but the pair at the left, and they end not at their companions’ faces, but somewhere else. It should come as no surprise that Lê used an ungainly, slow-operating large-format camera to expose what she calls the “theater of the real,” although pictures like these have much more in common with Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass than with what Barnard, using a similar contraption, was after.

This, some would say, is teaching the camera how to lie, but under a gentle hand it remains a startling vehicle for truth-telling, even if the truths being told are often nebulous. A youngster takes it easy in Mark Steinmetz’s Girl on Car, Athens, GA of 1996, her face as impassive, and yet as magnetic and mysterious, as that of an Ingmar Bergman heroine. Lost in youthful pensiveness, her eyes reflect what we cannot see, and entreat us to follow her there. In an image by Rosalind Fox Solomon, a pair of Mardi Gras princesses, bejeweled and coiffed, in gloves and white gowns, are silhouetted against a cloudless sky and budding trees. It isn’t a commercial shot. One girl bends over the edge of the float to stretch out her fingers for something; the other observes the exchange, adjusting her tiara and squinting in the sun. With the seriousness of children, both girls transcend their simple role in the pageant by unexpected displays of personality. “The depth is in the pictures, not what I say about them,” Solomon has remarked, acknowledging her own limited understanding of what the camera had wrought.

The same, and more, could be said for the ghostly, double-exposed plantation studies of Clarence John Laughlin, or Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s family tableaux—which are like any other American backyard photographs except that they pull us into a bizarre alternate world. It could be said, as well, for the much-fêted southern gothic of William Eggleston, whose photographs’ measure of arbitrariness and serendipity, of nostalgia, vivacity, anomie, and perfection, is no nearer to being fathomed today than when they burst into the public’s consciousness in 1976 with his first solo show at the Museum of Modern Art. Taken together, such images body forth an American South so complex and contradictory as to confound any master narrative of photography, or even of history.

Even in more painterly photographs—or those whose composition and messaging is tightly controlled—it’s possible to track the tendency of the world to intrude in unexpected ways. Consider Richard Misrach’s Swamp and Pipeline, Geismar, Louisiana, from his Cancer Alley project, commissioned in the ’90s as part of the High’s “Picturing the South” initiative. The photographer’s straightforward framing of his landscape, and the careful chromatic ranging of mints, whites, and straw yellows, are elements of the picture that we might have associated with painting. The forest of bleached trunks recalls an early Thomas Cole tour de force, Lake with Dead Trees (Catskill) (1825), although the works’ receptions likely differ. Within the Cole painting’s sublime totality, viewers may fail to notice a subtext that we could call environmentalist. Conversely, in Misrach’s photograph, the rusty pipe in the middle ground would seem to be the key detail. The miraculous algae bloom, which has transubstantiated poisoned standing water into what looks like solid ground, becomes merely a gloomy backdrop, a sort of pathetic fallacy to amplify the dire warning of the picture.

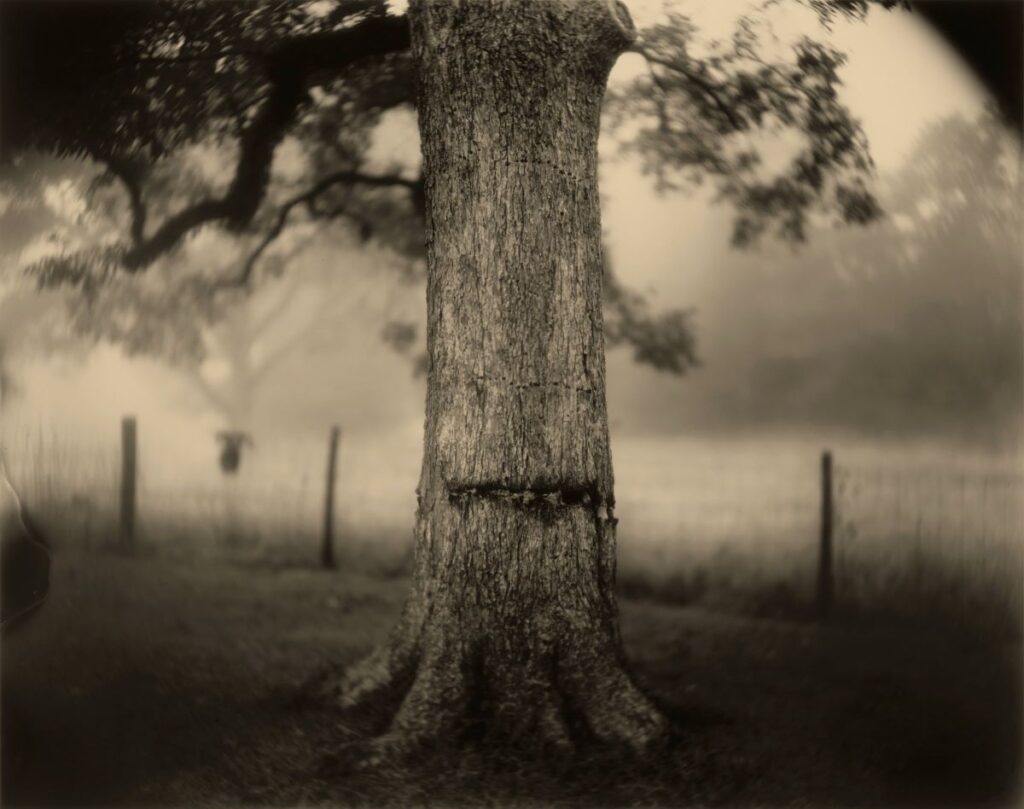

Another more lyrical example, Sally Mann’s Deep South, Untitled (Scarred Tree), from her series Motherhood, is an obvious metaphor for the South’s tortured history. But its physical subject, the oak holding up the world of the picture, is also, in the parlance of twentieth-century cultural theorist Roland Barthes, pure punctum: something that strikes us as meaningful even when we can’t pinpoint a historical or cultural significance that would make it so. One suggestion for approaching the pictures in this exhibition lies in an observation by John Szarkowski, MoMA’s late, longstanding curator of photography: “The history of photography has been less a journey than a growth,” he wrote. “Like an organism, photography was born whole. It is in our progressive discovery of it that its history lies.”

A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845 • High Museum of Art, Atlanta • September 15 to January 14, 2024 • high.org