How Frank Duveneck fostered the rise of a new painting genre in a coastal Massachusetts town

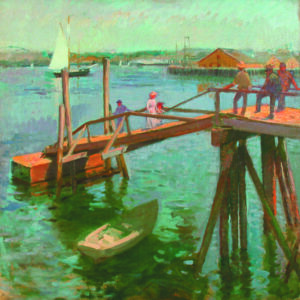

Fig. 1. The Yellow Pier Shed by Frank Duveneck (1848–1919), c. 1900–1905. Oil on canvas, 36 by 40 inches. Collection of Michael Owen and James Yost.

Frank Duveneck is not usually associated with Gloucester, Massachusetts, nor with paintings in an impressionist style. He has always been best known for the dark, Munich-style paintings he made at the outset of his career, and, in fact, most of his impressionist work from Gloucester was not exhibited until long after his death. While many of these Gloucester paintings are quick outdoor sketches, a few of them stand among Duveneck’s very best and most ambitious works, notably a remarkable view from Banner Hill, The Yellow Pier Shed (Fig. 1). These paintings deserve to be better known.

Through the summer classes he taught in Gloucester, Duveneck played a major role in transforming Gloucester into an art colony, and attracting other major American painters to work there. Figures such as Theodore Wendel, Willard Leroy Metcalf, John H. Twachtman, and Childe Hassam produced masterful impressionist renderings of Gloucester, many of them also portraying the vista from Banner Hill. Several of these paintings surely rank among the all-time masterpieces of American impressionism. Duveneck’s role in luring such gifted painters to this spot has been largely passed over, despite the extensive scholarly literature on his work.

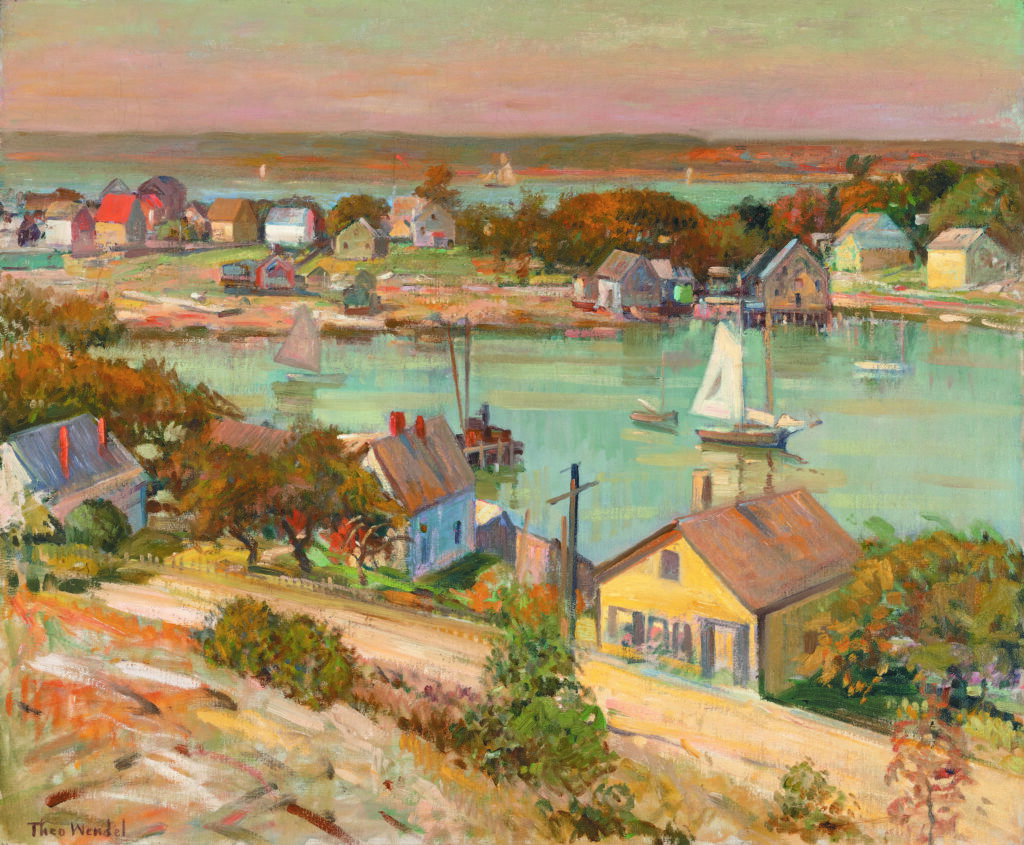

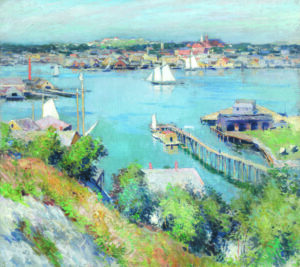

Fig. 2. Gloucester Harbor by Theo- dore Wendel (1857 or 1859–1932), 1900–1915. Signed “Theo Wendel” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 19 1/2 by 35 1/4 inches. Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago.

A little historical background will put Duveneck’s Gloucester work in context. He was born in Covington, Kentucky, just across the river from Cincinnati,and grew up in a German-speaking household. When he sought professional training in Europe, it was natural for him to attend the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. There he studied under Wilhelm von Diez, won awards, and mastered Diez’s approach of dashing brushwork applied to working-class subject matter. He was in his early twenties when he produced what remain the best-known paintings of his career, energetically executed studies of rebellious young working-class boys. The best known of these, in the Cincinnati Art Museum, is generally titled The Whistling Boy, although in fact the model is not whistling but smoking—exhaling the smoke from a cigar (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The Whistling Boy by Duveneck, 1872. Signed and dated “F. Duveneck 1872” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 27 7/8 by 21 1/8 inches. Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, gift of the artist.

These dark and energetically painted Munich-style paintings created a sensation when they were exhibited in Boston in 1875. They were effusively praised by William Morris Hunt, the leading artist in Boston at the time, and were praised in The Nation by Henry James, who declared that Duveneck was a specimen of “unsuspected genius.”1 It was with reference to these stunning early works that John Singer Sargent once remarked: “After all’s said, Frank Duveneck is the greatest talent of the brush of this generation.”2 Along with his abilities as a painter, Duveneck had a peculiar knack for gathering friends and followers around him. In 1875, when Duveneck returned to Munich after a three-year sojourn in the United States, he began to attract a following of American and English students. By 1877, when he visited Venice he was accompanied by a number of these young men, who became known as the “Duveneck Boys,” and who shared “an unusual spirit of companionship with their teacher.”3 When James McNeill Whistler fled to Venice, after being bankrupted by his libel trial against John Ruskin, the “Duveneck Boys” became his chief artistic companions.

In 1878 Duveneck started an art school for this group of young followers in Polling, Bavaria, and while the school lasted only a few years, they continued to follow him on his travels, as he moved in succession to Venice, Florence, and the United States. While the members of this group periodically broke off to pursue their own artistic pathways, they often reconnected with Duveneck years later. For example, John Twachtman, who studied with Duveneck in the mid-1870s, went on to further independent study in Paris and New York, but reconnected with Duveneck in Gloucester at the end of the latter’s career. Duveneck was painting alongside Twachtman just days before Twachtman’s untimely death in Gloucester on August 9, 1902.

Fig. 4. Smith Cove from Banner Hill by Duveneck, c. 1905. Oil on canvas, 25 by 36 inches. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Michael Owen.

Interestingly, Duveneck’s gift for attracting a following seems to have been based not so much on an overpowering personality as on the feeling of good fellowship that emanated from him—a quality so relaxed that it led some to accuse him of lack of ambition, or even laziness. The writer Elizabeth Pennell, who knew Duveneck in Venice, wrote of him:

Duveneck . . . was large, fair, golden-haired, with a long drooping golden mustache, of a type apt to suggest indolence and indifference. As he lolled against the red velvet cushions smoking his Cavour, enjoying the talk of others as much as his own or more—for he had the talent of eloquent silence when he chose to cultivate it—his eyes half shut, smiling with casual benevolence, he may have looked to a stranger incapable of action, and as if he did not know whether he was alone or not, and cared less. And yet he had a big record of activity behind him, young as he was; he always inspired activity in others, he was rarely without a large and devoted following.4

Similarly, artist Elizabeth Boott, who would marry Duveneck in 1886, noted his friendliness and kindness and his seeming lack of driving ambition in a letter to friends she wrote in 1879: “He is very nice, genial, simple & friendly & ready to talk by the hour & tell all he knows. He is the frankest, truest, kindest hearted of mortals & the least likely to make his way in the world. He is rather lazy, I fancy, & besides never looks at all to the main chance.”5

Fig. 5. View from Banner Hill, East Gloucester, photograph by Herman W. Spooner (1870– 1941), c. 1900. Cape Ann Museum Library and Archives, Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Interestingly, Duveneck stood out from most of his companions for his working-class background and inferior primary education. When he painted a portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell in 1877, for example, Blackwell’s adopted daughter Kitty complained: “It is disappointing to find so unusually clever an Artist speaking bad grammar and so unpolished in his manners. Aunt B. has given him some hints which I think may help him.”6 But she also clearly found him lovable and endearing, declaring: “If we remained long, it clearly would be a second case of adoption.”

Duveneck’s later career was almost entirely centered in Cincinnati and Boston, where he retained social connections with the students and supporters of William Morris Hunt, who enthusiastically praised his work and had been the teacher and mentor of his wife, Elizabeth Boott. Hunt died in 1879, but it was surely through him that Duveneck first learned about the picturesqueness of Cape Ann, where Hunt built himself an eccentrically designed studio in Magnolia, a small harbor town just a few miles south of Gloucester, in 1877.

In 1890 Duveneck organized a summer class of students from Boston and the Cincinnati Academy to work in Gloucester. This appears to have been the first large and ambitious class of this sort to take place in the town. By this time, the notion of capturing outdoor light in a fashion influenced by the French impressionists had become a major interest for American artists. In an article on Duveneck’s class, artist and author Helen Knowlton noted that he and his students worked outdoors, in natural light “with results that are almost startling in their truth—their absolute freedom from tradition and conventionality.”7 Duveneck clearly viewed this class as a means to not only teach others but also to teach himself the new impressionist approach to handling sunlight effects.

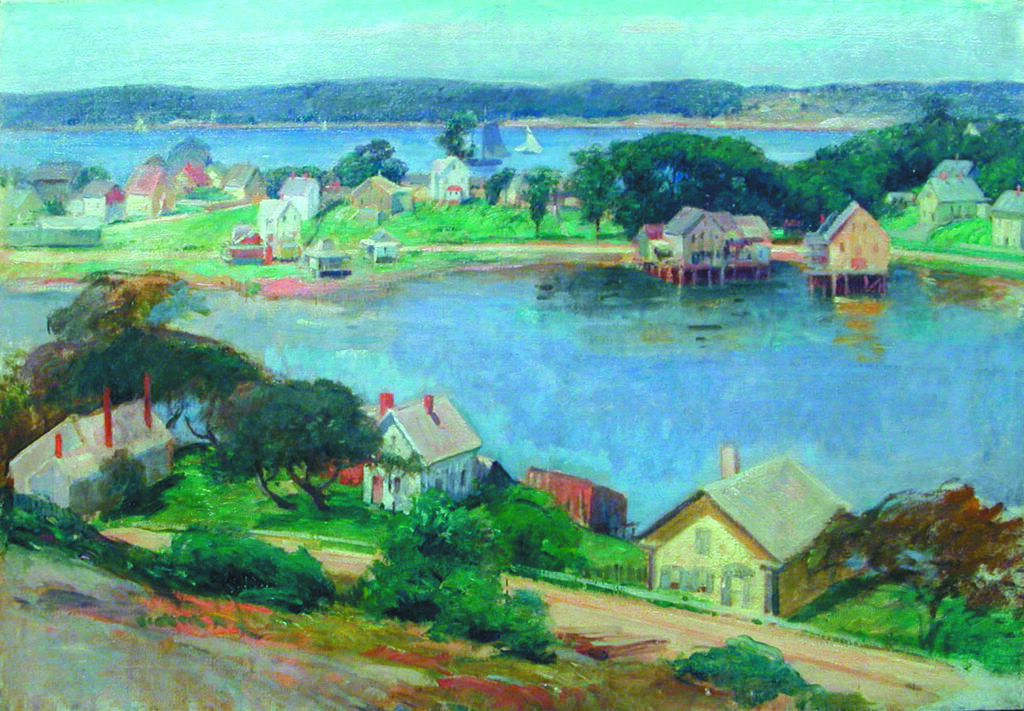

Fig. 6. Gloucester Harbor by John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902), c. 1900. Signed “J. H. Twachtman” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 24 3⁄4 by 24 7/8 inches. Arkell Museum at Canajoharie, New York, gift of Bartlett Arkell.

In the course of about fifteen summer excursions to Gloucester, over a period of nearly twenty years, Duveneck produced about one hundred impressionistic Gloucester paintings. Interestingly, he did not publicly exhibit these works or put them up for sale, and he continued to execute portrait commissions that were darker in palette and more conservative in approach. The whole group of Gloucester paintings was inherited by his son, and they seem to have been largely unknown until the 1980s, when they began to come up for sale and to be featured in museum exhibitions. It’s not clear whether Duveneck neglected to promote this group of paintings out of laziness, since he had a comfortable income, or whether he set them aside as a group in order to leave them to his son. In any case, given Duveneck’s own careless attitude toward this body of work, it was easy for scholars to be careless also, and they have been mentioned only in passing in the extensive scholarly writings on the artist.

The degree to which artists who visited Gloucester around the turn of the century had ties of one sort or another with Duveneck is suggested by a note in a local newspaper in 1900:

East Gloucester . . . Delightful Entertainment and Exhibit at Hotel Rockaway. . . During the season such prominent artists as Duveneck, De Camp, Churchill, Hazard, Pond, Potthast, Adams Case, Twachtman, Corwin, A. C. Fauley, L. S. Fauley, Katherine T. Farrell, Walter Clark and his son Eliot Clark, have arrived at the Rockaway, and in their coming the art of Massachusetts, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and the West have united in happy congeniality and the universal love of Gloucester and its never ending charms to the artist. Mr. Duveneck’s reputation as an artist and sculptor is too well known to need comment and his presence made all happy. 8

One could devote many pages to exploring the web of social connections between these artists, but it’s clear that Duveneck was the magnet that initially pulled together this group. For example, Charles Corwin, Wendel, and Twachtman all studied with him in Munich. Joseph DeCamp and Edward Potthast studied with him in Cincinnati. Long lists of names quickly become tedious, but it is clear that a large number of artists came to Gloucester because of their social ties with Duveneck in 1900 and in subsequent years.

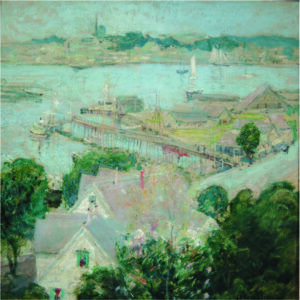

Fig. 7. Gloucester Harbor by Twachtman, c. 1900. Signed “J. H. Twachtman” at lower right. Oil on pan- el, 13 1/4 by 22 inches. Private collection.

Duveneck’s “school” in Gloucester was always somewhat peripatetic, but seems to have been centered on Rocky Neck, a peninsula on the eastern side of Gloucester Harbor. Over time his school evolved into the Rocky Neck Art Colony, which bills itself as one of the oldest continuously operating art colonies in the United States. Not surprisingly, many of the most notable American impressionist landscapes of Gloucester were painted from the high ridge just above Rocky Neck, known as Banner Hill in tribute to the local Wonson family, which raised a flagpole flying the American flag there at the outbreak of the Civil War. The site provides panoramic vistas of Smith Cove and Rocky Neck, the main channel of Gloucester Harbor, and downtown Gloucester, with its white church spire and the red brick Victorian spire of the town hall. The yellow pier shed that appears in many of these impressionist panoramas of Gloucester was owned by John Wonson.

Fig. 8. Ferry Landing by Edward Potthast (1857–1927), c. 1915– 1920. Signed “E. Potthast” at lower center. Oil on canvas, 24 by 30 inches. Private collection; photograph by Alan Geho, courtesy of Keny Galleries, Columbus, Ohio.

Today the work produced by Duveneck and his friends and students in Gloucester has been widely scattered, but among them are paintings made from Banner Hill by Wendel, Twachtman, Metcalf, and Hassam, as well as, of course, Duveneck himself. These have become recognized as masterworks of American impressionism and are widely reproduced in books on nineteenth-century American art. But they are generally not considered together as a group. Wendel spent several summers in Gloucester with Duveneck and took over his class for a week in 1890.9 On one of these Gloucester visits, Wendel painted Gloucester Harbor, now in the Terra Foundation collection (Fig. 2). Duveneck’s Smith Cove from Banner Hill (Fig. 4) is so close to Wendel’s panorama, even to the placement of a sailboat in the distance, that it seems probable that the two worked side by side. Remarkably, there’s also a photograph from Banner Hill taken by Herman W. Spooner at approximately the same date, which provides a gauge of how accurately the two rendered the scene (Fig. 5).

Like Wendel, Twachtman was surely lured to Gloucester through his friendship with Duveneck, and we know that in June of 1890 both Duveneck and Twachtman stayed at the Hotel Rockaway on Rocky Neck in Gloucester. Very likely, it was in this year that Twachtman painted two wonderful views looking down onto Rocky Neck from Banner Hill, one in the collection of the Arkell Museum at Canajoharie (Fig. 6), and the other formerly owned by Ira Spanierman (Fig. 7). In some cases, Duveneck and Twachtman painted the same scene, and may well have worked side by side, for example in their respective renderings of a pier with a dramatically sloping ramp (see Fig. 9). Twachtman’s last series of notable paintings was produced in Gloucester and he died there, unexpectedly, of a brain aneurism at the age of forty-nine in 1902.

Fig. 9. The Steep Ramp by Duveneck, c. 1900. Oil on canvas, 30 inches square. Owen and Yost collection.

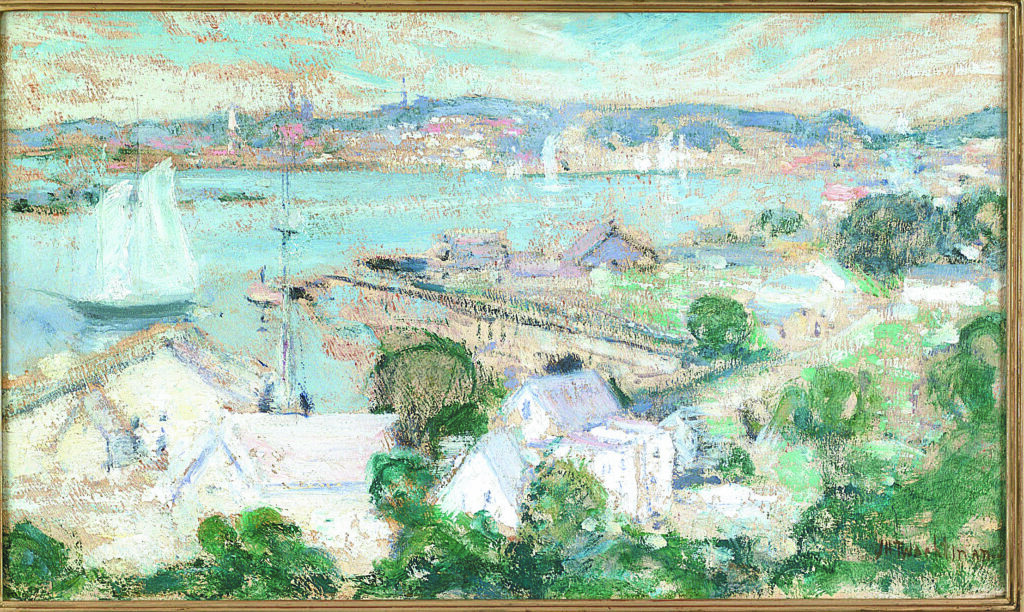

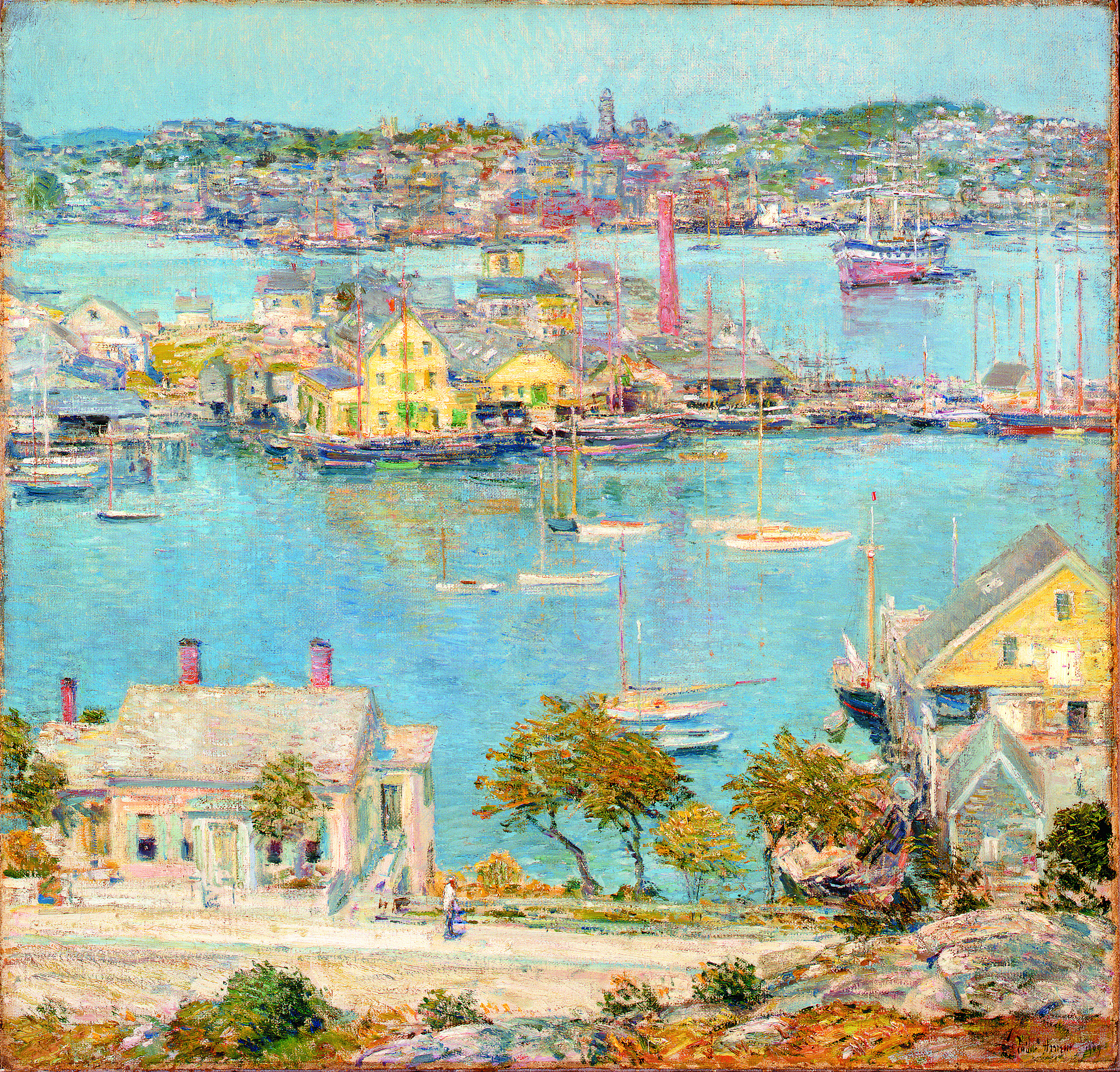

Metcalf was probably lured to Gloucester through his close friendship with Twachtman, whom he had known in Paris. In 1895 Metcalf and Hassam made a painting excursion together to Gloucester, and this resulted in what is arguably Metcalf’s masterpiece, Gloucester Harbor (Fig. 10), which won the Webb Prize at the Society of American Artists’ Exhibition in New York in 1896. Painted from Banner Hill looking westward, with the morning sun at the artist’s back, the painting combines the intense and broken color of the impressionists with a dynamic composition.

Hassam’s masterful Gloucester Harbor also shows the view from Banner Hill, looking down on the same fish shack that Duveneck featured, but from a standpoint a little farther to the left (Fig. 11). Most likely it was painted entirely outdoors, with the short staccato brushstrokes that Hassam favored. While most painters simplified and took creative liberties with the scene, Hassam clearly took care to represent every house and vessel with careful accuracy. His painting is cluttered with his visual response to every detail.

The main feature of Duveneck’s Gloucester masterwork, The Yellow Pier Shed, is the fishing pier of John Wonson, with a schooner tied to the dock. The view extends beyond to Rocky Neck and then across the harbor to downtown Gloucester. Duveneck simplified the scene into strongly architectonic shapes. The exceptional degree to which he did so becomes apparent when we compare his painting with the visual confusion of Hassam’s painting of the same subject. More than the other painters of this scene, Duveneck organized the colors into large bold patterns, as if they were building blocks, particularly the near complementary colors of the yellow shed and the blue water behind it.

Fig. 10. Gloucester Harbor by Willard LeRoy Metcalf (1858–1925), 1895. Signed and dated “W. L Met- calf, 95” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 26 1/8 by 29 1⁄4 inches. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Massachusetts, gift of George D. Pratt; photograph © Mead Art Museum / gift of George D. Pratt (Class of 1893) / Bridgeman Images.

It is interesting to set the paintings made from Banner Hill by Wendel, Twachtman, Metcalf, Hassam, and Duveneck in a row and consider them as a group and observe how different each artist is in his approach. Wendel’s canvas is the most matter-of-fact; Twachtman’s two paintings are the most mystical and ethereal, the most transcendental in effect; Metcalf ’s, with the wonderful liquidity of the sky and the blue water, is the most picturesque and evocative of the beauty of a summer’s day; Hassam’s is the most vibrant in recording momentary visual impressions; and Duveneck’s, with his bold handling of shapes and colors, is the most magnificent as a design. How these artists influenced each other is an interesting topic for speculation.

Surely, while Duveneck played an important role in luring these gifted artists to Gloucester, he himself greatly benefitted from what he learned from them. But what’s strikingly apparent is that while he’s famed as a master of dark Munich-school painting, Duveneck was also a master of American impressionism. His view from Banner Hill holds up well against the others; one might even argue that it is the best. What’s more, he was surely the magnet that attracted this group of remarkably gifted American impressionists to Gloucester. His role in the creation of one of America’s most notable and enduring art colonies deserves to be more widely known.

Fig. 11. Gloucester Harbor by Childe Hassam (1859–1935), 1899 or possibly 1909. Signed and dated “Childe Hassam 1909” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 25 by 26 1/8 inches. Hassam likely painted this work on a trip to Gloucester in 1899, but may have retouched and dated it in 1909, perhaps hoping to make it appear more recent and therefore more marketable. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, bequest of R. H. Norton.

1 Henry James, “Note,” The Nation, vol. 518 (June 3, 1875), p. 375.

2 Quoted in Norbert Heermann, Frank Duveneck (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1918), p. 1. Sargent made this comment at a London dinner party in 1896. See Julie Aronson, “A Tale of Two Cities,” in Aronson, et al., Frank Duveneck: American Master (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 2020), p. 46 and p. 49, n. 78; and Andrea Dombrowski, “Everything is Moist,” ibid., pp. 51–52, p. 67, n. 4.

3 Elizabeth Pennell, Nights: Rome, Venice in the aesthetic Eighties; London, Paris, in the Fighting Nineties (London: J. B. Lippincott, 1916), p. 84.

4 Ibid.

5 Quoted in Colm Toibin, “Frank Duveneck and Henry James,” in Aronson, Frank Duveneck: American Master, pp. 90–91.

6 Kitty Barry Blackwell to Alice Stone Blackwell, May 24, 1877, cited in Aronson, “A Tale of Two Cities,” p. 36 and p. 38, n. 49.

7 Helen M. Knowlton, “A Home-Colony of Artists,” Studio, July 14, 1890, p. 326, cited in Martha Oaks, Frank Duveneck, the Gloucester Years (Gloucester, MA: Cape Ann Historical Association, 1987), np, note 8.

8 Gloucester Daily Times, August 10, 1900, np. 9 Knowlton, “A Home-Colony of Artists,” p. 326.

HENRY ADAMS is the Ruth Coulter Heede professor of art history at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.