My first cookbook was a gift I received from my parents when I was ten or eleven years old: Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls—a delightful book with easy recipes and charming photography. I was hooked. Then, in the mid 1980s, when I owned just a few of what I call the “working” cookbooks I use for my job as a food stylist for commercial film and photo shoots, I started noticing oddball books available at flea markets and street fairs. They went for 50 cents, maybe a dollar, and had titles such as What Cooks in Suburbia, Saucepans and the Single Girl, and The I Hate to Cook Book. Soon I had a shelf filled with these oddities. It was then that my husband-to-be, interior decorator Thomas Jayne, encouraged me to start collecting American cookbooks seriously. He felt they represented an under-appreciated area of American culture (and as a Winterthur Fellow, he knows what he is talking about). Well, forty years and nearly five thousand books on American foodways later, I offer up this smattering of what I have collected.

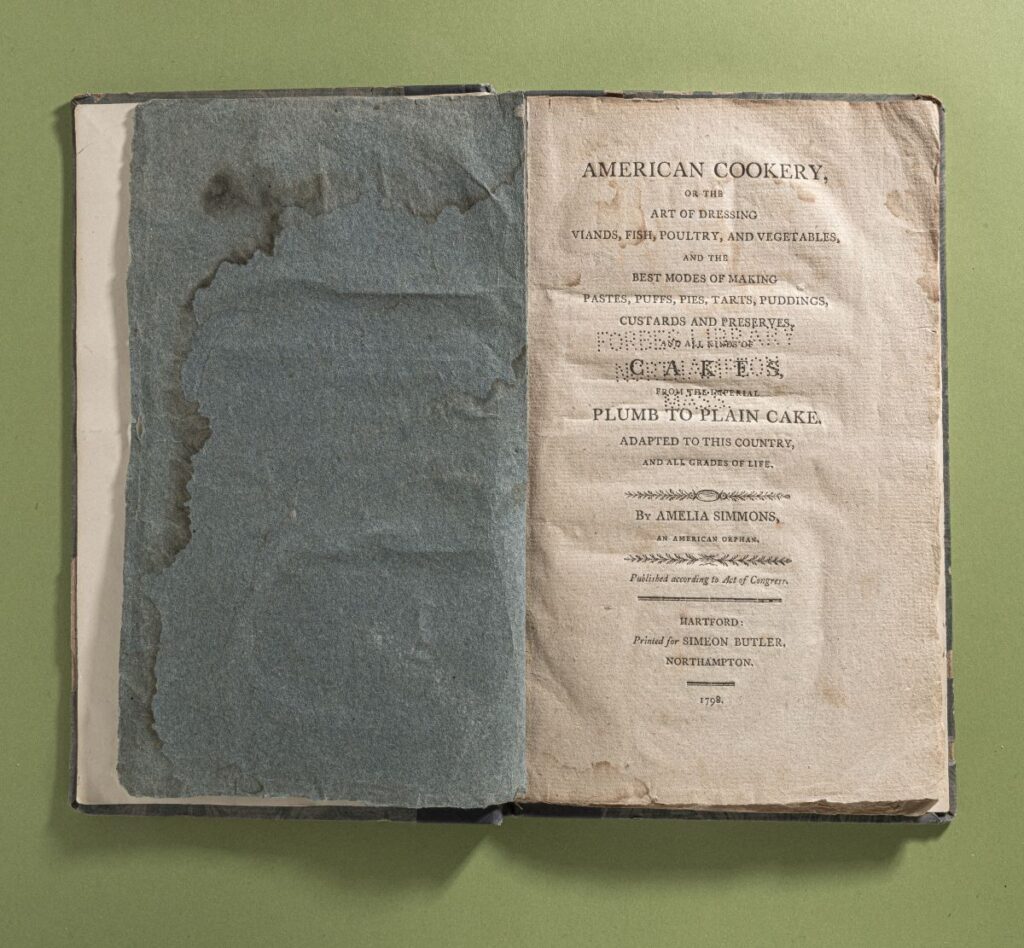

American Cookery by Amelia Simmons (first edition, Hartford, Connecticut, 1796; my edition, 1798)

Considered the first “American” cookbook by an American author, it is not, however, the first cookbook published in America. Several English books were reprinted here during the eighteenth century. While a great many of the recipes in American Cookery do come from English cookery books of the period, this book is notable for its inclusion of several quintessentially American ingredients—for example, it includes five recipes using corn meal. Also notable is the self-description that Simmons added to her byline: “An American Orphan.”

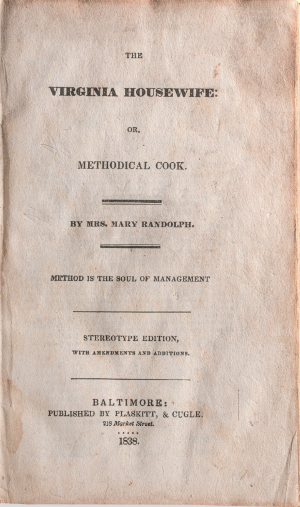

The Virginia Housewife by Mary Randolph (first edition, Washington, DC, 1824; my edition 1838)

The Virginia Housewife is regarded by several noted food scholars as the first truly “American” cookbook—especially because of its extensive use of domestic and newly imported ingredients, as well as indigenous preparation techniques. Extremely popular, the book was published in many editions during the early nineteenth century. Mary Randolph was the granddaughter of Thomas Jefferson and spent considerable time at Monticello. I like to think a bit of Jeffersonian rationalism is reflected in the book’s subtitle: “Method is the Soul of Management.”

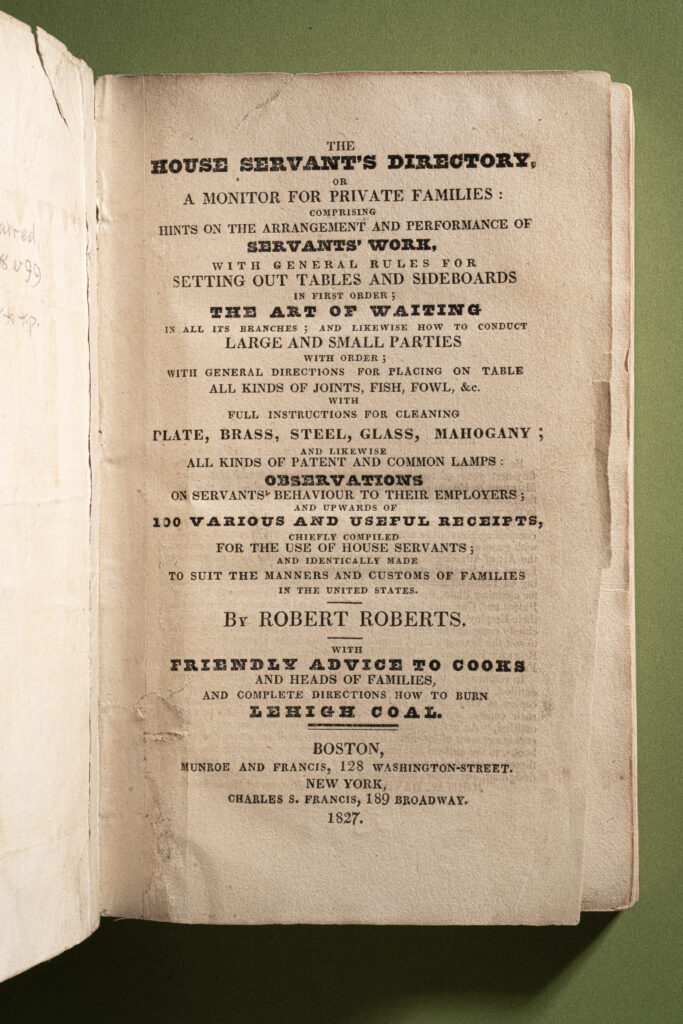

The House Servant’s Directory by Robert Roberts (first edition, Boston, 1827)

While technically not a cookbook, it is probably the most important early American treatise on household organization and administration. It is also one of the first commercially published books written by an African American. Roberts was the butler for US senator and governor of Massachusetts Christopher Gore. The title page describes the many topics covered in the book, which became the standard reference on the subject of domestic management for many years.

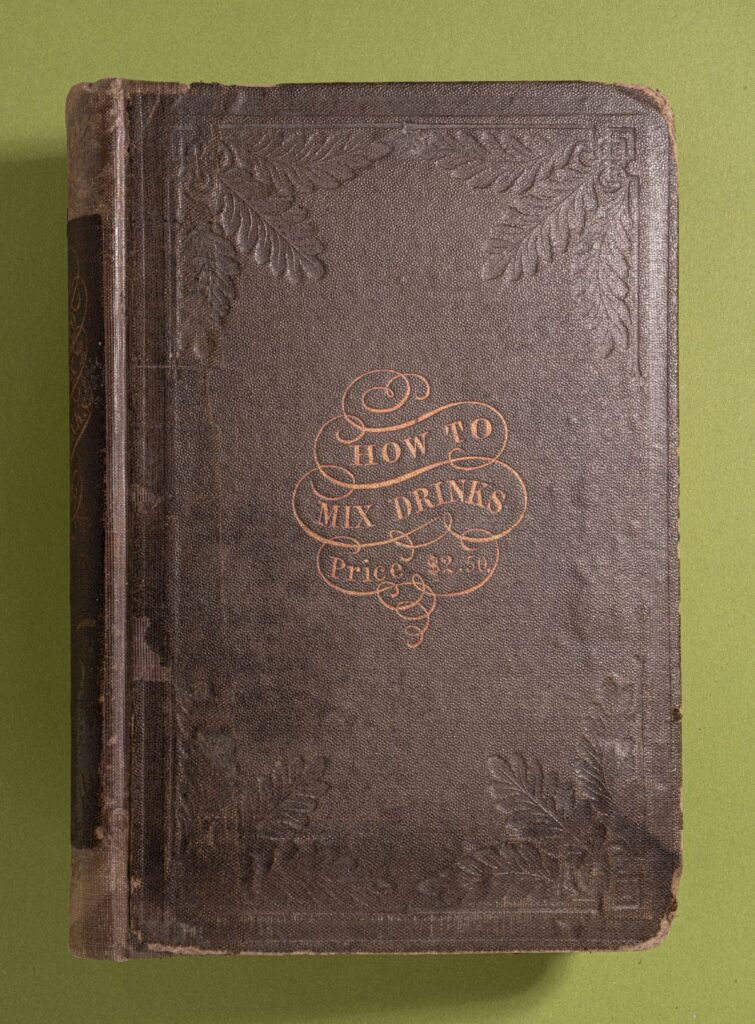

How to Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas (first edition, New York, 1862)

The first real cocktail book published in America, the subtitle is among my favorites: “The Bon Vivant’s Companion.” Jerry Thomas, known as “the father of mixology,” owned and operated several bars and saloons in New York City. Among the many recipes, more than several of which were his own creations, are two of the more famous nineteenth-century concoctions—the Blue Blazer and the Corpse Reviver.

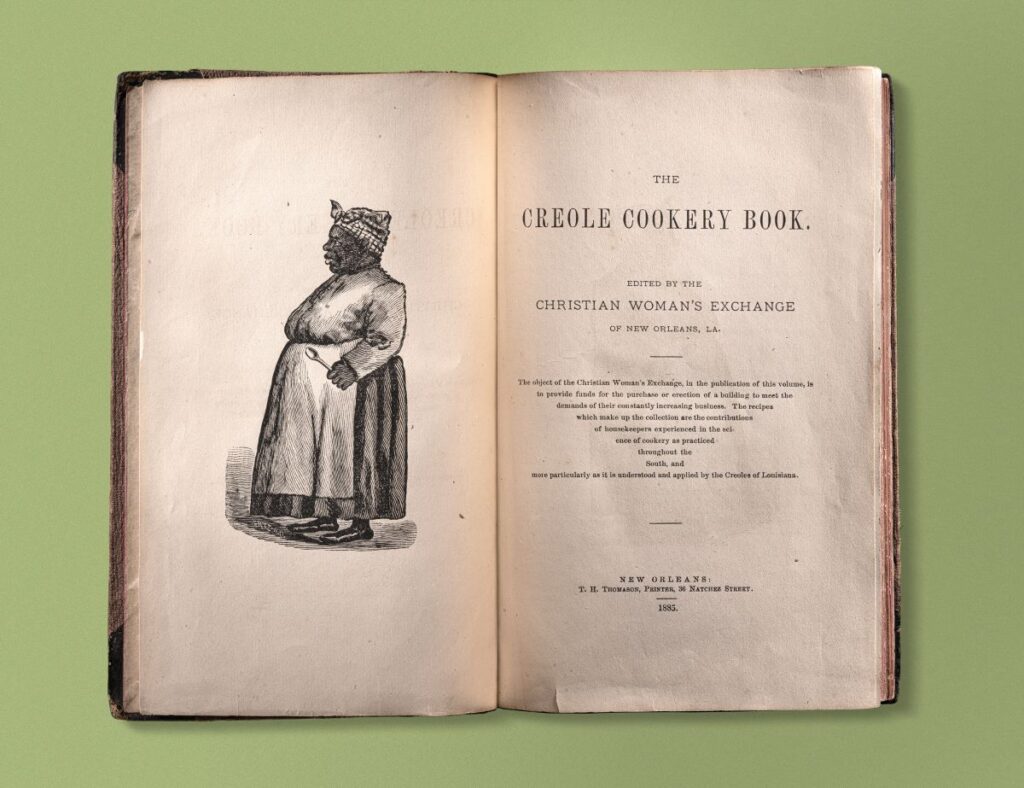

The Creole Cookery Book, ed. Christian Woman’s Exchange (first edition, New Orleans, 1885)

To quote the title page: “The recipes which make up the collection are the contributions of housekeepers experienced in the science of cookery as practiced throughout the South, and particularly as it is understood and applied by the Creoles of Louisiana.” Hence the wonderful illustration, printed on the cover and opposite the title page: an homage image to the home cook. While Lafcadio Hearn’s book, La Cuisine Creole, is generally thought of as the first book on the subject, it was in fact published shortly after The Creole Cookery Book.

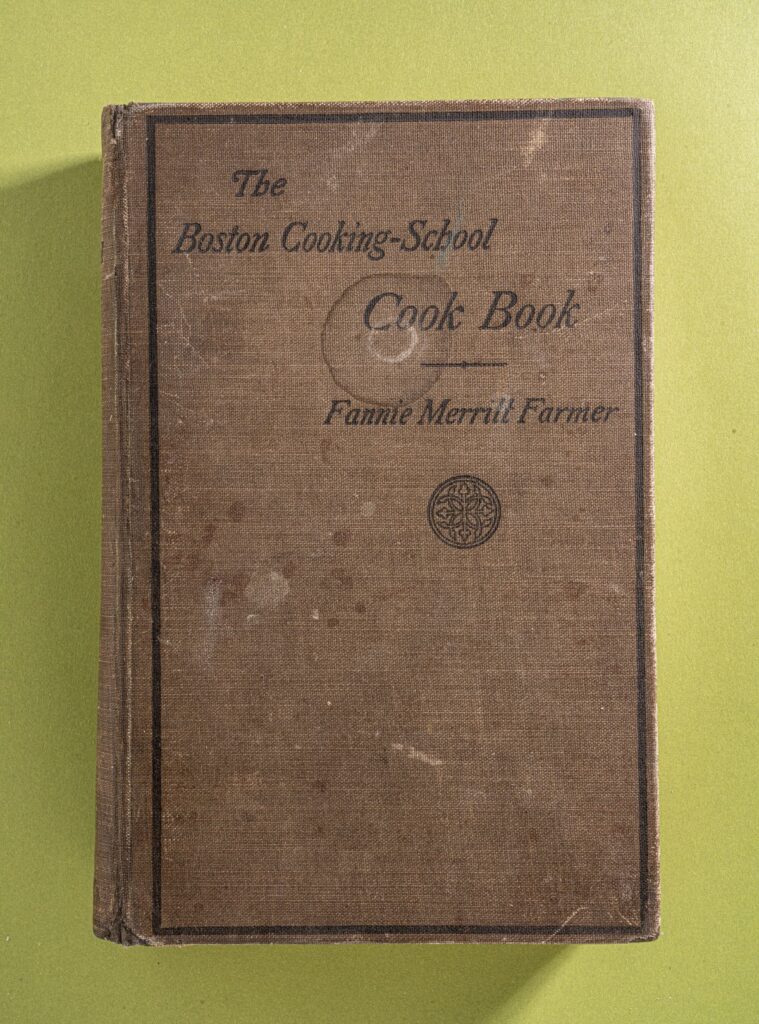

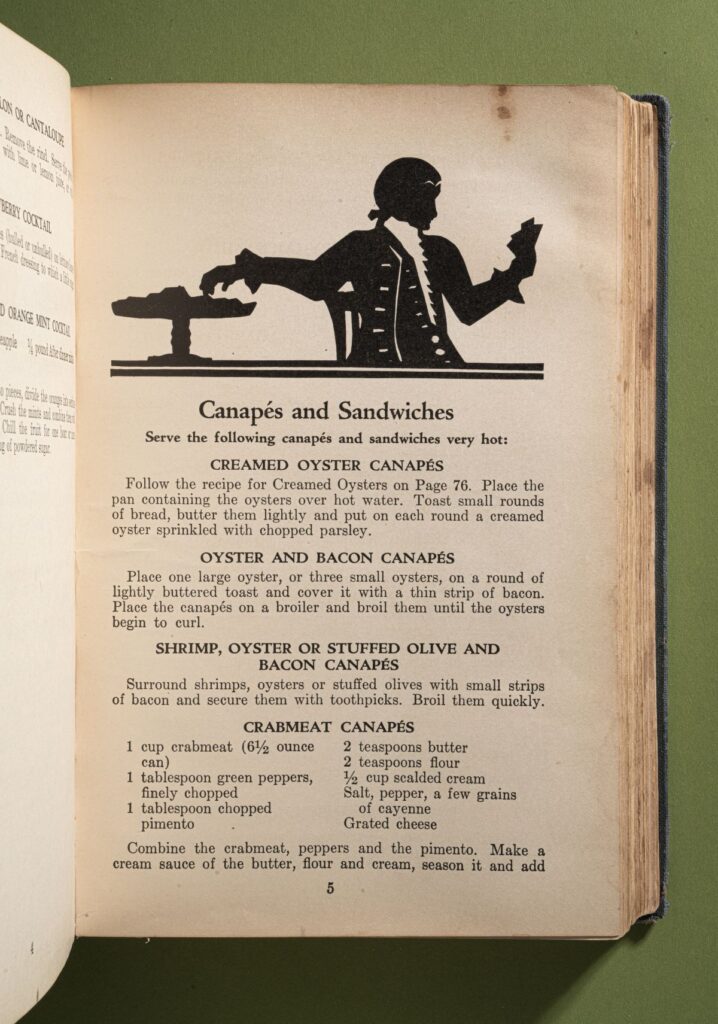

The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by Fannie Merritt Farmer (first edition, Boston, 1896)

I am extremely fortunate to have a first edition of this book in my collection—a thoughtful and generous wedding present from one my husband’s clients. The first printing was limited to three thousand copies. The publishers were not confident it would sell due to the fact that two years earlier, the then-president of the Boston Cooking-School, Mary J. B. Lincoln, had published a not dissimilar book. Fannie Farmer took a more methodical approach to writing recipes, offering detailed instructions, standardized measurements, and precise cooking times and temperatures. This was my mother’s go-to cookbook when I was growing up. I still use her dog-eared copy.

The Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer (first edition, St. Louis, Missouri, 1931)

At age fifty-four, Irma Rombauer—an upper middle-class housewife and noted hostess—had three thousand copies of this book printed using her own funds. I am privileged to own two of those copies. Though I have never seen one with a dust jacket, the original 1931 edition featured an incredible illustration of Saint Martha of Bethany, patron saint of cooks, slaying a dragon.The wonderful drawings throughout the book were done by Rombauer’s daughter, Marion. Still in print and wonderfully updated, this is the book I recommend to friends who want to learn to cook—as it is the book from which I taught myself to cook while in college.

Picture Cook Book by the editors of Life magazine (first edition, New York, 1958)

One of the first coffee-table-cum-cookbooks (if not the only one), Picture Cook Book features photography that was groundbreaking for its time, with images taken by a notable list of contributing photographers, including Arnold Newman and Eliot Elisofon. This mid-century gem offers, as one reviewer wrote, a look into “late-1950’s aspirational suburban American dining and entertaining.” It was a precursor to the lavish,over-scaled lifestyle cookbooks that began to appear in the 1980s. The photo spread of the cocktail party is one of my all-time favorite food photographs—note the platter of Fritos and dip on the far side of the table.

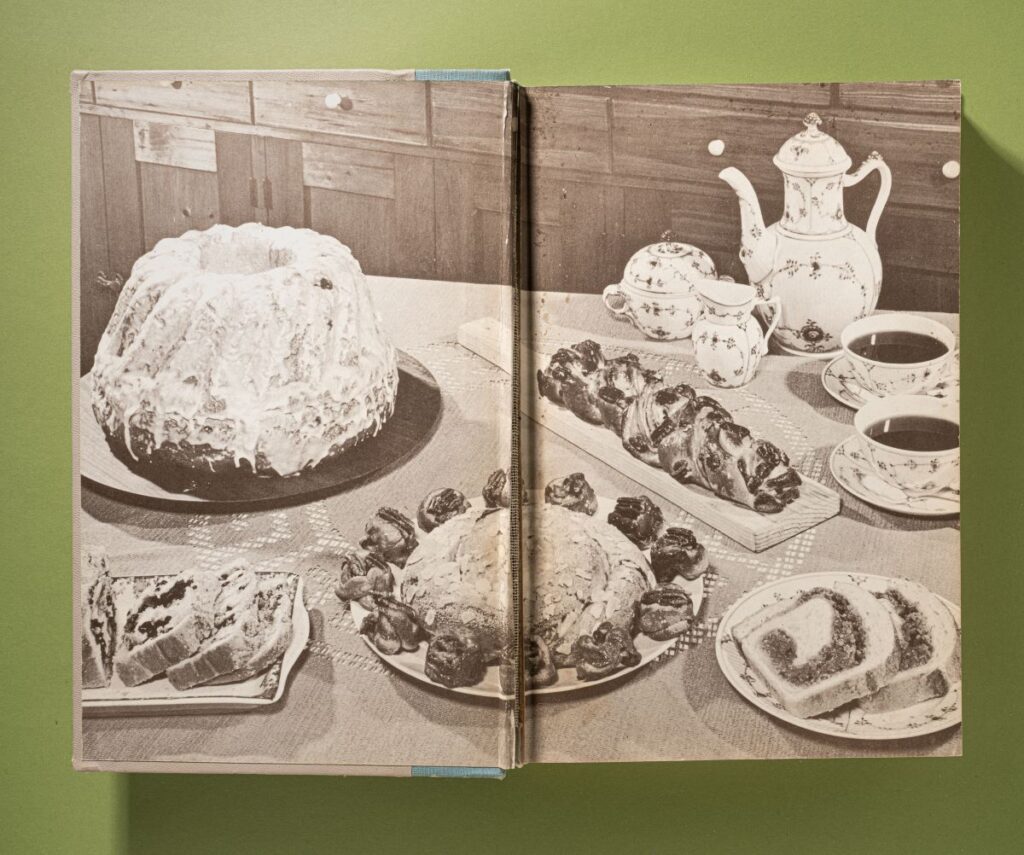

The Art of Fine Baking by Paula Peck (first edition, New York, 1961)

I do not remember when I acquired this book, but it is the first I refer to when I want to bake something. Though the book is not illustrated, the instructions are thorough and precisely explained. The recipe for angel food cake, for example, covers eleven pages. The book is truly an unsung classic in my collection.

Publication of American baking books first boomed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the railroads made the produce of the great wheat fields of the Midwest widely available, and the technological advances in the refinement of flour, sugar, and leavening ingredients—not to mention refrigeration—made home baking accessible. I have no shortage of these books in my collection, as evidenced by row after row of wonderful trade bindings.

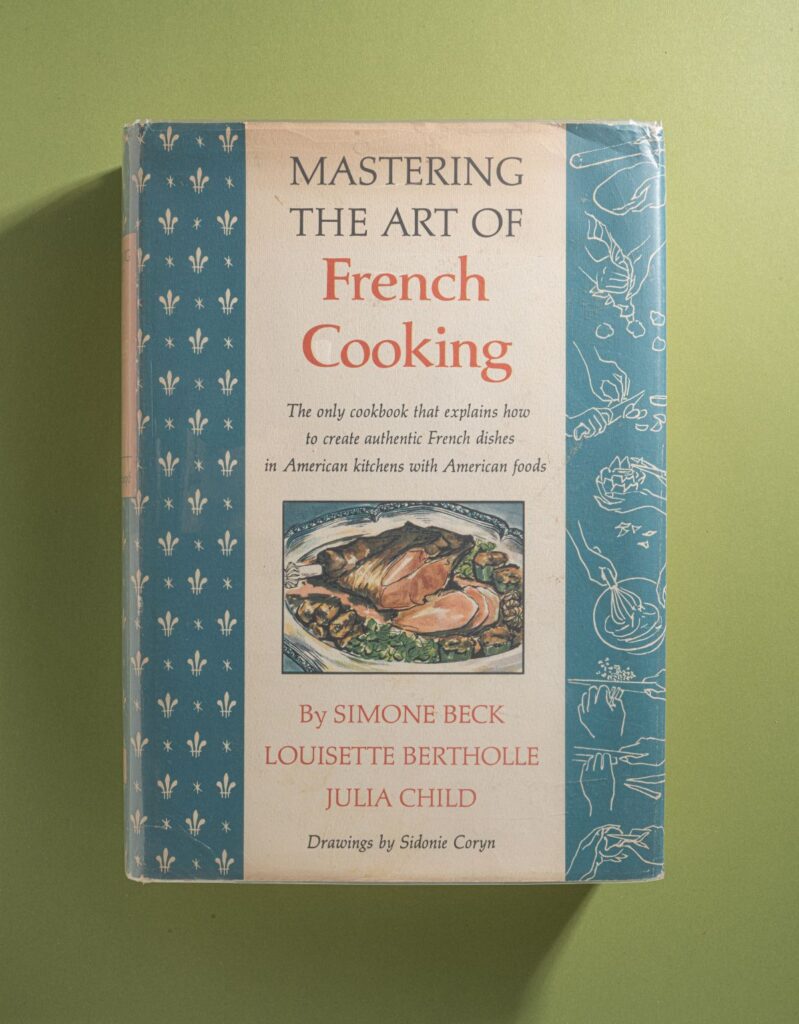

Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle, and Julia Child (first edition, New York, 1961)

There is not much I can add about the profound influence this book and its subsequent editions have had on American cuisine and cooking. It took me years to find a first edition, first printing, and then many years more to ask Julia Child to sign it for me. That happened when Thomas and I attended a dinner and book signing for her last cookbook at the James Beard Foundation. We were last to have books signed, and Child, who was famously six feet, two inches tall, insisted that Tom—who checks in a six foot, seven—escort her down the stairs to the dining room. “Rarely,” she said, “do I have a man taller than myself on my arm.”

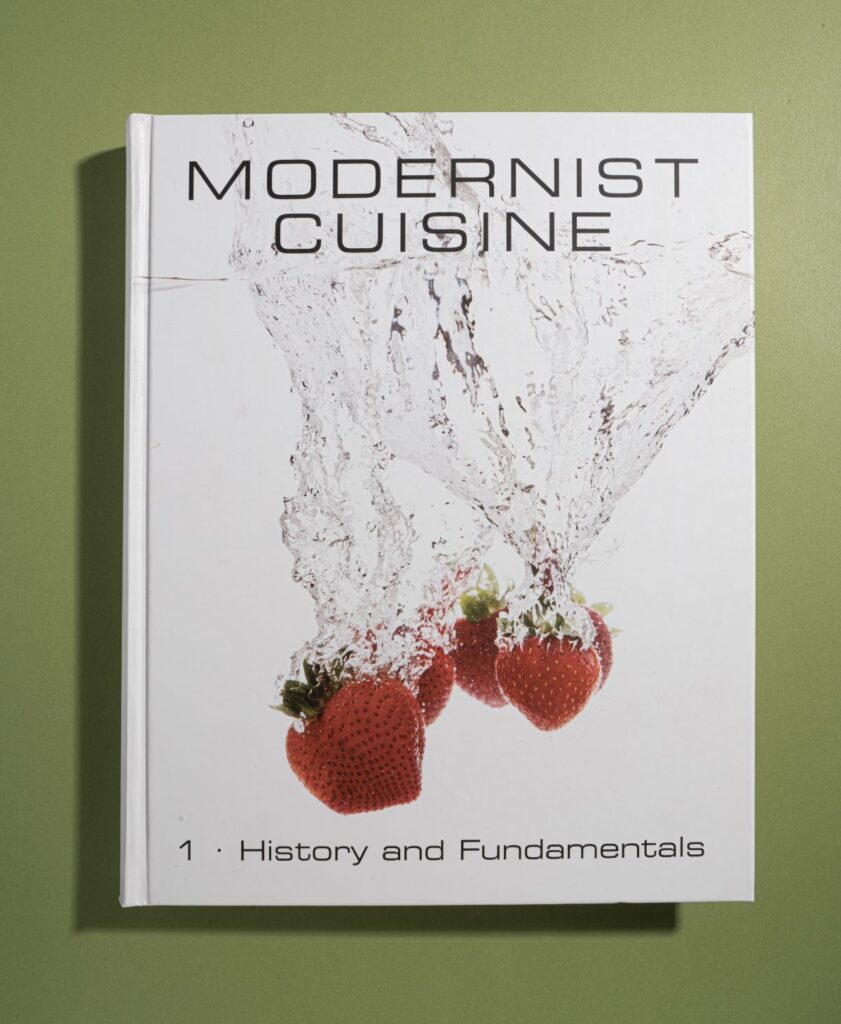

Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking by Nathan Myhrvold, Chris Young, and Maxime Bilet (6 vols., first edition, Bellevue, Washington, 2011)

Comprising five hard-bound volumes, 2,438 pages, and weighing fifty-two pounds, this encyclopedia of contemporary cooking must be seen to be believed. The photography is stupendous. To keep my collection comprehensive and up to date, I felt it had to be included. (Thank you, Tom, for the extravagant Christmas present.)

In addition to being a food stylist and an avid collector of books on American foodways, RICHMOND ELLIS was a consultant and stylist on the Martin Scorsese film The Age of Innocence, and a contributor to the Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons. He is a member of the Culinary Historians of New York, the International Association of Culinary Professionals, and the Southern Foodways Alliance. He is also a new member of the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of American History Kitchen Cabinet, and is a member of the advisory board of the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans, where he has a second home.